Happy day-after-Thanksgiving, everyone. There’ll be some new content next week for paid subscribers (it’ll go to unpaid subscribers a week or two later), but in the meantime: From 2009 to 2012, I taught in a rather unusual sixth-grade classroom in a small charter school in North Carolina. These three essays from 2014, which most of my readers will not have seen, talk about my teaching philosophy and what went into my decisions as an educator.

(I went looking through all my old writing, looking for what I thought was the most underrated/underappreciated stuff, and this was what I settled on. I’ll republish some other old stuff from time to time as I get the blog more fully under way.)

Educ 101: Axioms

I’ve been teaching more or less continuously for fourteen years. My first job ever was at Lee Brothers Tae Kwon Do academy in Burlington, North Carolina, where I became an assistant instructor a few days after I turned fifteen. I continued to work at Lee Brothers all the way through college, and graduated with a degree in middle grades education from UNC Chapel Hill. From there, I spent three years working the kinks out of an interdisciplinary, project-based critical thinking class for sixth graders, after which I moved to Seattle and spent another two years working my way to the top of a parkour gym. This fall, I hope to find a place with an adult education nonprofit in the San Francisco bay area, teaching students and professionals to overcome biases and other flaws in thinking and reasoning. In short, while I’ve never considered myself to be a teacher, I’ve done a heck of a lot of standing up in front of people and spouting words at them.

And I’ve noticed—while listening to students and parents, and while watching the work of my colleagues—that whatever vague, amorphous thing is meant by the phrase “teaching philosophy,” mine is unlike everyone else’s. There have been plenty of cases of convergent evolution—where my colleagues and I would independently arrive at similar conclusions regarding best practices—but I have yet to meet another person in the world of education who actually holds the same goals that I hold, and thinks about those goals in anything like the same way.

So this is my attempt at a manifesto. Right now, I’m imagining it will clock in at somewhere around 20,000 words, in ten to twenty installments. [Note: I got through three essays and then other writing projects took precedence, but I may still release 104 and 105 someday].

In the tradition of Marx, Smith, and Luther, I’m going to do lots of approximation, simplification, and hand-waving; I have the feeling that if I tried to include every caveat and equivocation, I might just run out of parentheses.

I am, however, going to confine myself to the realm of actual experience, so if you find yourself suspicious that there’s no way these ideas could really work in the real world, remember that they did, at least once, and at least well enough that I never got fired and chased through the streets with torches and pitchforks.

(If you find yourself horrified, that’s perfectly normal, and the support group meets on alternate Tuesdays.)

So! Let’s begin. I have no plan and no actual idea where this series will go; I’m just going to start with the low-hanging fruit, and see where we end up. For reasons which will become clear by the end of this post, I’m going to phrase almost all of this as if I’m talking about educating kids, though I’ve logged a roughly equivalent amount of time working with adults.

Big Idea #1: Kids Are People, Too

Notice the lack of a “but.” This is the first and most significant tenet of my heresy—most teachers, if pressed, will profess to believing in child personhood, but they usually follow it up with something about frontal lobe development not being completed until age twenty five, or with some example of how they dissociate their present selves from who they were in middle school. Few, if any, will admit that some kids are simply terrible people1, or list a student among those whom they admire and aspire to emulate, or feel comfortable putting an eleven-year-old in a position of real power or responsibility and then actually turning their backs and letting things play out.

Yet in my fourteen years as a teacher, I have found absolutely nothing to shake my belief that the range is the same for both kids and adults. Granted, I haven’t spent much time with students under the age of, say, eight. But if there’s a difference for middle and high schoolers, it seems to be nothing more than a slight shifting of the bell curve’s peak.

To those who will point out, “Um, but there is a lack of development in the frontal lobe that doesn’t go away until age twenty five,” I respond that, first, this does not stop us from giving plenty of responsibility to eighteen-to-twenty-four-year-olds, and second, that it’s better to err on the side that will promote growth and self-worth than the side which promotes condescension, infantilization, and (ultimately) stagnation. [And third, it turns out that that’s just not true, and is a factoid which the social telephone game misinterpreted and blew out of proportion.] Which is about as close as a segue as I’m likely to get to my second point:

Big Idea #2: The Teacher Is Not In Control

This one feels a bit like cheating, as it’s really just an extension of #1. But it’s worth underlining as its own point, because it informs a lot of what I do in terms of classroom management and the creation of a learning atmosphere.

The core insight here is that everyone who is present at a given lesson is there by choice. This does not always feel true, since society is built around making its norms and restrictions feel inevitable and impermeable. But just like the lines on the pavement don’t actually stop you from driving on the wrong side of the road, the rules and incentives that keep kids in the classroom don’t actually force them to be there. Their presence is always a choice.

Teaching students to recognize this truth is always one of my earliest priorities. It’s empowering in a way that’s a necessary precondition for mature growth, and it gets them thinking in terms of constrained trade-offs, which are what make the world go ‘round.

(This is usually where the teacher is in control—you can’t force a particular choice on another human being, but you can limit their options and offer incentives).

It frees me from the role of shepherd, and allows me to become more of an antagonist or foil (more on that later). Most importantly, it leads to the recognition that learning is in fact optional, and that, in turn, encourages students to look critically at the pros and cons of their decision to pay attention.

Which is as close as I’m likely to get to a segue into my final axiom:

Big Idea #3: Some Kids Left Behind

You cannot save everybody.

(Actually, since I’m speaking out of my own limited experience, let me rephrase: I cannot save everybody. Perhaps there are teachers out there who can.)

If I make boots, and I try to sell them for a thousand dollars a pair, I may find one or two buyers and make a couple thousand dollars. If I sell them for two dollars a pair, I may find a near-infinite pool of buyers, but I will likely be unable to cover my costs. Somewhere in the middle, there is a balance of price and demand that nets me maximum profit—make the boots more expensive, and I lose buyers faster than the higher price can make up for; sell them cheaper, and the gain in buyers is not offset by the loss-of-profit-per-pair.

This is one of the central ideas of economics, and it’s at the core of what makes capitalism work. It’s part of the magic that results in goods being produced only as often as they’re actually wanted, and that allocates them according to who wants them the most. It’s one of the elements of a system that produces the maximum possible wealth and surplus.

It’s also a process that is entirely blind to things like fairness and suffering. It routinely results in winners and losers, rich and poor. To the extent that we, as a society, try to correct these imbalances, we do so at a loss in total wealth—we can ensure that there are no true losers, but only by introducing constraints and inefficiencies that bring the final number down.

There is an analogous situation in education. We can arrange our schools such that the maximum amount of material is taught, and the maximum degree of potential fulfilled (accepting the fact that this will result in clustering and inequality), or we can arrange them such that every child reaches a certain level of erudition, at the cost of a reduction in the aggregate.

Let me be clear—I am very glad that we live in a society which cares about the disadvantaged. I have tremendous respect for special education teachers, for urban remediation, for ESL programs. But I would be lying if I pretended that these were jobs I was suited to perform. My own instruction is filled with take-it-or-leave-it opportunities, with absolute minima of quality and pass-fail assignments, and with multipliers that need something significant to multiply. As a result, I tend to turbocharge the gifted, challenge the average, and only very occasionally inspire the struggling or the apathetic. There is a certain type of student who—whether because of attitude or because of native ability—does not respond to my teaching style, and I’m essentially comfortable with this. It’s my belief that more good comes from my held line than from other teachers’ held hands, and this belief is at least partially borne out by the results.

And that’s it. Like Euclid, I’m attempting to build a solid, internally consistent framework atop as few assumptions as possible. As I start to formulate proofs, I may backpedal and realize I’ve forgotten a critical premise, but for the moment, I encourage you to take a few minutes to think about how your own school experience would have been different, had your teachers embraced my three fundamental axioms. Even better—if you assume that these three things are true, how would that change your opinion of what the ideal school should look like?

Educ 102: Economics

Where we last left off, I had made three fairly strong claims about the underpinnings of education: first, that one should treat middle schoolers and high schoolers almost exactly the same as one would treat adults (in other words, as humans); second, that the locus of control belongs in the students, not in the teacher; and third, that any given teaching environment needs a clear definition of what constitutes “acceptable losses.”

I’d like to spend this post digging a little deeper into an economic model of classroom management that ties all three of those axioms together into one coherent framework. I expect that you’ll find the philosophical stuff relatively benign and obvious (it’s mostly common sense and Econ 101). But following those precepts to their logical conclusions can lead to some surprising recommendations.

Costs, not consequences

I have a close friend who once told me that she thinks of speeding tickets in the same way she thinks of taxes or tolls. She drives about 13 miles per hour over the limit pretty much all the time, and about once every other year, she makes a large payment for that privilege. This isn’t just a metaphor—she actually did some rough calculations to estimate the value of the time she was saving and the risk and magnitude of various speeding penalties to arrive at her decision to speed by 13mph (no more, no less).

While I don’t necessarily endorse her particular conclusions, I was deeply impressed by her reasoning. By treating the situation as transactional rather than punitive, she was assuming total control of it—it wasn’t a question of right or wrong, or of whether the cops were being fair, or of trying to get away with something. She simply took the constraints of the law as a given, and made a choice within them.

There’s a lesson in there for teachers (and, by extension, for students). We’ve all experienced some version of the following, in the classroom—either directly, or as bystanders:

Hey—HEY! No talking while I’m talking! No—I don’t want to hear your excuses. We’re halfway through the year; you should know better by now. Your classmates are here to LEARN—your constant interruptions are rude and selfish, and now we’re losing even MORE time because I have to stop and deal with you AGAIN. I’m taking away your recess—in fact, no, you know what? I’m tired of this—no more recess for you until next week. Maybe THAT will finally teach you a lesson.

This is a bit of a strawman—I’ve exaggerated a little to hit all of the failure modes in a single example—but it’s not that far outside of the realm of the ordinary. Unpack this, and what do we find? A student whose inappropriate behavior is seen as fundamental—as indicative of his or her core character. An adult who is acting as judge, jury, and executioner, handing down moral condemnation and arbitrary punishment without hesitation. A black-and-white universe in which there is only one set of priorities—those of the curriculum—and no room for accommodating the needs or preferences of the human beings stuck inside.

This is the kind of system that produces graduates who yell at traffic cops for pulling them over, who curse bad luck or injustice when they have to pay a ticket, who think of themselves as being at the mercy of fate. It’s not a system that encourages students to mature and take control, because it offers no incentives for doing so—at best, it reinforces elementary self-control in the form of conformity to authority.

A far better paradigm is one designed to encourage the sort of transactional thinking exemplified by my speedy friend. For example: in my sixth grade classroom, there were four levels of permission-to-talk, indicated by a poster at the front of the room with a movable magnet. If the magnet was set to “Active,” students were free to move and talk at will. If it was set to “Participating,” everyone was expected to be focused on the central discussion or activity—depending on the goals of the moment, people might be allowed to blurt, or might be expected to raise their hands; side conversations were allowed, to a point. On “Quiet,” students were permitted to whisper, but NOT to talk or murmur—we would practice the difference from time to time, to reinforce the standard. And on “Silent,” any talking at all was considered an infraction.

There were a handful of consequences associated with quote, misbehavior, endquote (most often a partial silent recess, in which you would have to sit on the curb for five minutes while your friends got to run around and play). I made it clear very early in the year that there would be no warnings given—if you spoke aloud on Quiet (or at all on Silent), I would assume that this was a deliberate choice on your part, and respond as if you were in total control of yourself and acting in your own best interests.

What I would not do is bring subjective moral judgments into the situation. Rules and consequences are about influencing the frequency with which certain behaviors appear. Guilt and shame and retribution are certainly methods one can use to bring about results, but they come with tangible (and often enormous) downside—they erode student confidence where effective, and corrode the student-teacher relationship where not. If I saw too much unwanted behavior occurring, the solution was not to start shouting, it was simply to increase the price such that fewer students were willing to pay it.

Of course, if you truly commit to this model, then you also embrace the fact that some students will take that option, just as there’s always someone who’s willing to speed and risk getting a ticket. This is not, in fact, a bad thing—with the right framing and encouragement, you can actually turn the whole misbehavior phenomenon into one giant teachable moment:

What if you could pay in advance to break the rules? If, for instance, I let you sit out at recess BEFORE class, and then gave you one freebie—what would you spend it on? The real question isn’t “should I talk,” it’s “if I get caught talking, will it have been worth it?” If your best friend is having the worst week of her life, and you think of a hilarious joke in the middle of a quiz, maybe making that joke and getting a silent recess is TOTALLY WORTH IT, because five minutes sitting out is a small price to pay for cheering up your friend—just like a speeding ticket every now and then might be a small price to pay for the freedom of going faster every day.

In this way, I encouraged my students to assume total agency within the constrained system of the class rules. I made no judgments of their behavior—I simply enforced the known prices of various actions, keeping hidden costs (like “you’ll get lectured, too”) out of the equation. For instance, some of my colleagues had rules forbidding bathroom breaks during class. If pressed, they would hem and haw, and often give in; the magnitude of the consequences for the student (if any) depended entirely on the teacher’s subjective sense of the situation. I, on the other hand, simply set the price at one silent recess and moved on; this led to both an overall reduction in bathroom break requests and to me not having to make moral judgments every time someone had to pee.

I treated my students as if they were rational agents in total control of their own behavior, and by the end of the year, they had actually made significant progress toward that ideal. As an added benefit, I rarely found myself the target of frustration over rules and consequences. When they thought something was unfair, they didn’t blame me—they either blamed the system (and treated me as their ally in improving it), or they blamed themselves (and felt motivation to grow). It’s the difference between shouting “WHY DID YOU DO THAT??” and calmly asking “So, was it worth it?” The former assumes that You Are Right, And They Are Wrong; the latter assumes nothing. One is how you treat children, and the other is how you treat human beings.

Information markets

There’s a truism in economics that goes something like “the more available a thing is, the less value it has.” We pay premium for diamonds and very little for glass or cubic zirconia, and while availability is not the whole story, there’s power in noting that the relationship is causal in all directions. That which is rare is perceived as valuable; that which is widely coveted eventually becomes scarce; et cetera.

Hold that thought in your mind for a moment, and consider what implications it has when you apply it to the words “school” and “knowledge.”

The first time I tugged on this thread, it led me to a place that looked and felt something like this:

There’s the teaching that we intend to do, and there’s the teaching that we actually do, and the two are often different. It’s no surprise that many students fail to get excited about the information they’re being offered—from their perspective, it’s roughly as abundant as dirt. By shoving it down their throats, we’re implicitly sending the message that they wouldn’t want to eat it otherwise. If you don’t happen to be intrinsically motivated to learn, school is basically one long chain of “eat your broccoli” experiences.

Teachers fight this implicit narrative as hard as they can—creating engaging lesson plans, selecting compelling content, highlighting the relevance of each bit of knowledge and its application in everyday life. But the very fact that students ask the question “Why do we even need to learn this?” is indicative of a problem. After all, the information they’re treating as an imposition is something mathematicians spent generations trying to prove, or archaeologists spent years uncovering, or psychologists spent decades teasing out of the data from a hundred different experiments.

As it turns out, the obvious solution is, in fact, devastatingly effective. In my sixth grade classroom, I took steps to make information more scarce, and saw an immediate and dramatic increase in student engagement. It’s like the difference between handing someone a crossword puzzle or giving them a page torn from a dictionary—each contains similar content, but only one is naturally engaging.2

The poster-child for this pet theory of mine was a question limit. Each student had a default limit of one question per day; barring things like tests, they would receive a complete and honest answer to one and only one question during the fifty minutes they spent in my class. Students could earn additional questions through various means (some students even earned a “permanent” second question), but all questions asked counted toward one’s daily limit. If, for instance, a student were to ask “Can you help us with this?” I would answer “Yes,” check them off for the day, and walk away.

The result of this policy was a tangible improvement in the quality of my conversations with students. They quickly learned to prioritize the gaps in their knowledge, thinking critically about which things they needed to know, which they could figure out on their own, and which were trivial or irrelevant. They would routinely spend several minutes crafting a carefully worded question that would net them multiple pieces of information. They paid more attention to one another, as well—another of my interventions was a policy of never repeating myself, so they learned to listen whenever one of their colleagues was receiving an answer.

Perhaps the most encouraging development was the emergence of a secondary market in questions. About half of the projects in my classroom were partner- or group-work, and on many occasions, I would overhear sentiments like “Oh, man, we get to ask four questions; this is going to be easy,” only to walk by five minutes later to hear “I’m not going to ask that! You can waste your question on that; I’m saving mine for something good.” During my three years, I heard questions bartered for future questions, for pencils, for snacks, for help with homework in other classes, and for the chance to have the ball first during four-square at recess. I even had students attempt to buy additional questions off me by volunteering to sit out at recess—I’ll let you draw your own conclusions as to my likely response.

And the question limit was only the beginning. Wherever possible, I reduced the amount of information available at the start of an activity to a reasonable minimum. Sometimes further detail had to be extracted through questions; sometimes it was hidden in clues and ciphers; sometimes it was distributed unevenly throughout the room, and students had to choose to collaborate, often in the face of local incentives encouraging them to do the opposite. Once in a while, I even had the luxury of being able to structure a project in tiers, such that the completion of the first sub-challenge gave them the keys to the next. The result was a classroom experience that was less like steamed broccoli and more like a video game or an obstacle course.

There’s more to be said, but the clock is pushing midnight and the word count is pushing 2500, so this seems like a good place to press pause. The contextual conclusion is “learn basic economic principles, and apply them to your classroom;” as always, the overarching message is “assume your students are human beings, and that methods which explain and influence human beings will also explain and influence your students.” Next post will be another broad outline (titled “Antagonistic Learning”), after which we may be able to start talking about specific lessons I taught, and the lessons I took away from them. Your homework, should you choose to accept it: think of three things your teachers said they didn’t want you to do and then promptly rewarded you for doing.

Educ 103: Antagonistic Learning

Author’s note: This entry is quite long, and has two main parts. The first is a fictional example; if you wish to skip it, scroll down to the second image, which marks the start of the regular blog post.

PASS (excerpt, ch. 1)

…when the entire room had fallen quiet, Ms. Palmano turned to the dry erase board behind her and drew four large columns, labeled A, B, C, and D. She capped the marker, and then, as an afterthought, uncapped it and added the word (grades) after the letter D. Stepping back into the corner of the room, she spoke.

“I’d like you all to come add your names to the board, please.”

No one moved. Everyone looked at one another, then back at the teacher, who stood expectant, her arms crossed. Cautiously, a girl named Katie raised her hand. Ms. Palmano nodded to her, and she asked, “Should we put our name under the grade we want? Or the grade we think we’re going to get?”

“Is there a difference?”

Again, they all looked at one another. Holt caught Conor’s eye, and jerked his head toward the front of the room, raising his eyebrows. Conor shook his head, firmly.

Rolling his eyes, Holt stood and strolled casually to the board. Picking up a red marker, he wrote HOLT in large capitals right across the center of the board, with the HO in the B column and the LT under C. Then he walked back with his hands in his pockets, whistling provocatively.

There was a smattering of nervous laughter as the class waited for Ms. Palmano’s reaction, but she gave none. Eventually, two other students stood up, and then the floodgates opened. Soon there was a scrum at the board as the seventh graders fought for colors and pride of place.

“Why are we doing this?” asked one boy as he waited outside the pack for a marker.

“I thought we might start with a moment of honesty,” Ms. Palmano answered. Only a few students were close enough to overhear, Conor among them.

Quietly, he picked up a black marker and added his name in small letters right underneath Holt’s; there were ten or eleven other kids who had also chosen to straddle one of the lines.

When they had all retaken their seats, the teacher reached into her desk drawer and pulled out a phone. Holding it up, she photographed the board. “Well,” she said dryly, “half of you cheated.”

Another nervous chuckle.

“I think I can fix it, though. If a solid A is a 95, and a solid B is—what, an 89?—then I suppose I can give Arianna a 92.” Arianna shifted uncomfortably as everyone’s eyes fell on her; her name was written across the boundary between A and B. A moment later, though, they all turned back to the front as Ms. Palmano picked up her gradebook and began writing, looking back and forth from the board to the page.

“Wait—what are you doing? Are those really our grades?” This from another boy, one whose name Conor didn’t know. He sounded slightly panicked, and from the looks on the faces of the students around him, he wasn’t alone.

“Yes,” Ms. Palmano replied, still looking from the board to the gradebook.

“For what?”

“You tell me. You’re the one who gave it to yourself.”

“No, I mean—what’s the grade for? Is that, like, a quiz grade? Or a homework grade?”

“Oh. I don’t know. I was just going to put it onto your report card.”

There was a wave of incredulous protest as the teacher finished writing and put her gradebook down. Turning to face them, she hoisted an expression of exaggerated innocence onto her face and asked, “Is there a problem?”

A dozen voices spoke all at once, and she lifted her arms in a calming gesture. Slowly, the voices quieted, and were replaced by a dozen raised hands. She pointed to one.

“But we haven’t done anything yet!”

“So? You’re going to—isn’t this easier? Now we both know what to expect.”

Another outburst, this time involving at least half of the class. Again, Ms. Palmano waited, and again the students slowly settled and raised their hands. Conor looked over at Holt, whose eyes were narrowed, his expression mistrustful.

A girl spoke. “If those are our grades for the quarter, what’s to stop us from just doing nothing?”

“I hope you’re not suggesting that it would be a good idea to cheat in my class, Miss—”

“Gibson. Susanne Gibson.”

“Are you saying you plan to cheat, Susanne?”

Susanne fell silent, her cheeks flushed. Someone else spoke in a stage whisper. “Wish I’d put myself under A instead of C.”

“Cheating, Mr.—”

“My name’s Ben.”

“And twice a cheater—you didn’t wait your turn.” She called on another boy in the front row. “What’s your name?” she asked.

“Rami, ma’am—and can we change our grades?”

“CHEATING!” she roared, and the class was evenly split between those who laughed and those who cowered. “One does not simply change a grade!”

“But we didn’t know what the grade was for!” protested the boy who’d spoken first. There was a general mutter of agreement, smothered by the stern gaze of Ms. Palmano as she swept it around the room. Conor eyed his classmates furtively. Not all of them were joining in—half of the class was still just sitting there, indifferent—but those whose hands were raised looked mutinous. Holt’s frown had disappeared, and a tight, quiet smile was now playing around his lips.

“The grade is for your work in this class, which I thought was perfectly obvious from the fact that I wrote it down in my gradebook,” Ms. Palmano said. She called on the girl sitting directly in front of Conor.

“What work, though?—and my name’s Jennifer.”

“You tell me, Jennifer. You’ve promised me”—here she paused, scanning the board—“an A’s worth of English work. What will it be?”

“Aren’t you supposed to tell us? You’re the teacher!”

“And you’re the student. Would you rather learn how to follow directions, or how to write them?”

There was a lull as the protesters digested this. Holt was now laughing silently; Conor reached over and punched him in the arm. “What’s so funny?” he hissed.

“This whole thing,” Holt whispered back. “Está jodiendolos—they’re all taking it so serious, and she’s just trolling them. I bet she didn’t even write those grades down in her gradebook. Bet she was just taking attendance. Oh, man, I hope she doesn’t get fired.” He started laughing again.

Hands were going up into the air once more. The teacher called on another boy, who identified himself as Jeremy. “Are you saying we’re supposed to make up our own assignments?”

“I’m saying there are no assignments. But you owe me for that B you’ve asked me to sign off on.”

“What if we can’t think of anything?”

“Then you’ll fail.”

“There aren’t any failing grades up there,” Ben pointed out. “You only went down to D.”

“Oh, I’m not saying you’ll fail the class. Then you’d just be right back here next year—how would that help?”

“Wait—are you saying we can’t fail?”

“Of course you can fail—weren’t you listening? I’m just saying that your grade has nothing to do with it.” She threw her hands up in frustration. “Look, this is a very simple concept. I don’t know why you’re having so much trouble with it.”

“You’re not explaining it!”

“Exactly!”

The discussion dissolved into chaos. Conor watched with clinical interest as half of his classmates came unhinged. Some were like Holt, who now had tears shining in the corners of his eyes as he goaded those around him. Others—like Susanne—looked stricken, their voices pleading as they struggled to be heard over the angry shouts of Jennifer and the boy whose name Conor still hadn’t caught. There were plenty who sat in silence, and their reactions were no less varied—some looked pensive, others anxious, others merely bored. A few, like Conor, gave nothing away as their eyes moved back and forth across the room.

And there in the center of it all, making no effort to temper the bedlam she had unleashed, stood Ms. Palmano, that small, knowing smile returned to her lips as she waited for her students to wear themselves out.

She did this on purpose, Conor thought. Holt is right—she’s jerking us around.

Strangely, the thought produced no feeling of resentment, perhaps because he himself had not been swept up in it. She’s playing us for fools, but we don’t have to play along. He wondered what Ashleigh would do in this situation. Probably go up and erase the board. Or declare the class dismissed and walk out. Or…

Conor hesitated. A beautiful idea had just struck him—but it couldn’t be that simple, could it? He looked around the room, at the pandemonium still raging unabated. Slowly, he reached into his binder, took out a sheet of paper and a pencil, and laid them on his desk.

Ms. Palmano winked at him.

Oh, Ash would just love this….

He picked up the pencil and wrote his name and subject at the top of the page. Then, looking up at the board, he also wrote the number 85, and circled it. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Holt following his lead; a moment later, the girl in front of him, Jennifer, withdrew her voice from the tumult and did the same. Slowly the idea spread, in fits and starts, like ripples radiating out from Conor’s corner, until a tipping point was reached and the whole room fell silent. Then there was only the zip of bookbags and the click of binders, the rustle of paper and the scratching of graphite and ball points…

Antagonistic Learning

I am not what you would call a “normal” teacher. My sixth grade classroom was weird, to the point that even in the third and fourth quarters, I would frequently get messages from parents saying things like “Alex just loves your class—he talks about it almost every day after school! What—um—what exactly is it that you teach?” By now, you probably aren’t surprised to hear that I wrote the passage above, or that it’s unashamedly autobiographical.

In my first EDUC post, I tried to give an explanation of my axioms—the assumptions underpinning my decisions in the classroom. In the second post, I tried to describe some of the ways I operationalize those assumptions into concrete norms and expectations. Now, I’d like to pull back and talk about the overall atmosphere—about what it feels like to be a student in one of my classes.

“I am your enemy, Ender—the first one you’ve ever had who was smarter than you. There is no teacher but the enemy. No one but the enemy will ever tell you what the enemy is going to do. No one but the enemy will ever teach you how to destroy and conquer. Only the enemy shows you where you are weak. Only the enemy tells you when he is strong. And the rules of the game are what you can do to him and what you can stop him from doing to you. I am your enemy from now on. From now on, I am your teacher.”

—Mazer Rackham, Ender’s Game

My culture has a long and venerable tradition of fictional teachers who are capricious, demanding, unhelpful, derogatory, cryptic, and generally unpleasant to be around. Often, they are cynical old masters, numbed by the repeated failures of their previous students and no longer interested in scattering pearls before swine. Our hero has to spend enormous amounts of time and energy just proving that she is a worthy pupil, and there’s usually at least one falling-out halfway through the training in which it seems that the teacher will absolutely refuse to go any further.

Conspicuously absent from this archetype is any indication that the teacher is Doing It Wrong. In fact, while the student will often rail or rebel, this almost always leads to temporary disaster, after which she returns to finish her training. Though the relationship inevitably softens into one of mutual respect, it’s either implied or stated outright that the pupil could not have succeeded without that initial harshness—that the master’s way was in fact a critical component of victory.

There are lots of reasons why this archetype doesn’t actually show up in, say, public middle school classrooms. It’s largely based on a mentor-protégé model, whereas real classrooms have 20–40 students in them. It’s a take-it-or-leave-it, in-or-out paradigm, where our culture is increasingly committed to the spirit of “no child left behind.” It makes no accommodation for different learning styles, or for disabilities, or for outside factors that impact learning potential (such as poor home life or access to resources). It’s also not the kind of model that one can realistically build consensus around—in fiction, the only person that needs to be convinced is the student, whereas in reality there are the other teachers on one’s team, the parents, the administration, and external constraints imposed by the department of education.

Yet the romantic model persists. And when you ask people about the teachers they found most influential—the ones they feel true gratitude toward—a disproportionately high number of the stories you get back play around in this space. Sure, there are the teachers who are overflowing with love and support and encouragement, the maternal figures who comforted us and bolstered our confidence. But there are also the stern, aloof, emotionally distant ones, who demanded our absolute best, and offered not a shred of love or respect until it had been paid for in full.

In my corner of the United States, the transition from fifth grade to sixth grade (around age ten) is a big deal, often involving an entirely new building and a significant ratcheting-up of both freedom and responsibility. This means that, on the day my students first met me, most of them were somewhere in the space of nervous/off-balance/uncertain/actively panicking.

Knowing this, I structured my introductory lesson accordingly. Students would line up outside my door (for “Core Connections,” a name that gives few hints or clues) and enter to find the following:

A pile of roughly fifteen slightly-askew microwave-sized wooden boxes

A digital clock on the wall, counting down from 59:59

A teacher with duct tape over his mouth and a sign that read “THINK.”

In the space of that hour, they would either succeed or fail at a) recognizing that there was a problem to be solved, b) reaching a consensus as to what that problem was, c) devising a strategy for solving it, and d) successfully coordinating with one another to put the plan into action.

Each of the three years that I taught, three out of the five classes successfully built an eight-foot catenary arch with no help from me beyond the occasional grunt or wink. A fourth class was usually well on their way toward a solution, and a fifth was hopelessly lost.

That was where Core Connections began. On day two, I gave my students a lecture about free will and agency, and then opened the door and invited any students who were present against their will to leave. On day three, they walked in to find a full page’s worth of instructions written on the board in an unknown cipher with a single clue. Other early highlights included the establishment of a no-warnings policy for minor infractions, a limit of one question per student per day, a refusal to give any instruction twice, regular use of deadlines enforced by the countdown clock, and a grading schema under which following all directions perfectly resulted in a B+.

I’m fairly certain that if my plan had been subjected to review, I would have been forced to abandon it. What I was attempting was, after all, firmly in the category of high-risk/high-reward, and at its core, the American education system is strongly conservative and risk-averse. Luckily for my students, no one really bothered to check in on me until the end of the first month, at which point we had a demonstrably good thing going. My students were reflective, autonomous, hard-working, and well-behaved—not only on absolute scales, but also relative to those same students’ conduct in other classrooms.

In part, this was attributable to my specific content, which had the advantage of being more novel and more engaging than math, science, English, and social studies. The fact that I was the only male teacher on the team probably helped, too, along with the unusual structure of my classroom (with computers lining the walls and a large open space that could be filled with folding tables). But I claim that the single largest factor was my commitment to the model of antagonistic learning. From day one, I presented myself as a nemesis—a hoarder of information, a trickster, an Unreliable Narrator whose role was primarily that of an obstacle to be overcome and an opponent to be beaten. Most importantly, I spoke to my students with something far closer to brutal honesty than any other adult in the school was willing to give them.

It’s important to pause for a moment and point out that at the heart of antagonistic learning is a single, straightforward concept: people are not their actions.

I repeat this point for emphasis. People are not their actions.

If you’ve read some of my other posts, you will know that I’m interested in making this point less true. I think the world is a significantly better place when people’s true selves more closely resemble the sums of their actions (or rather, the reverse—when the sums of people’s actions resemble their true selves). However, when dealing with regular ol’ imperfect humans, it’s critical to keep in mind that there is a gap between one’s revealed self and one’s internal sense of who one is.

This is what lies behind the psychiatric model of unconditional high regard—for the purposes of therapy or treatment, even “terrible” people need a safe place to exist, where they can look at their behavior objectively without needing to spend energy on framing or being defensive. It plays a similar role in the antagonistic classroom, because the antagonistic teacher pulls no punches when it comes to evaluating student work, student habits—even, broadly speaking, student thinking.

It’s crucial, therefore, to hold the students themselves as inviolate—dignified by default, and capable by assumption. This is the key that makes antagonistic learning a successful model, and it must be explicitly reinforced—the antagonistic teacher may express disappointment that her students have failed to reach the bar, or skepticism that they’ll even bother to try, but never ever ever may she imply that her students simply lack the necessary ability. Indeed, the explicit assumption that they have the ability is what gives power to her critique. “Come on, you’re better than this, what happened?” is a recipe for growth, because the disappointment is proportional to the missed potential rather than to the distance to some ungrounded standard.

I don’t actually have a rigorous, prescriptive definition of what antagonistic learning entails. For me, it’s largely instinctive—I know it when I see it, because I have a deep internal model of what it looks like done right. But I’ll try to paint the picture in broad strokes:

Default skepticism. In the standard American classroom, there is a tendency to focus on the idealized potential of the students—to implore and exhort each person to do his or her very best at every turn. Most teachers spend a great deal of time on the narrative of excellence, describing highly effective processes and high-quality products in detail, hoping to paint an attractive picture that will draw students forward.

The antagonistic teacher, on the other hand, takes it as a given that most students will put forth the bare minimum of effort, and structures his class accordingly. He makes clear exactly what is necessary to achieve a B or a C (rather than presenting these as inferior shadow derivations of A-level work), and then ends his spiel, ideally leaving the students with the vague sense that they’ve just been insulted.

There’s a strawman version of this method that is rightly criticized as “death by lowered expectations.” This is different, though—the antagonistic teacher doesn’t act as though her students aren’t capable of doing better, but rather as though she doesn’t expect them to try. It’s a form of reverse psychology:

Oh, right, sorry—I didn’t talk about what it takes to get an A because most of the time nobody’s interested. I mean, it’s not that it’s HARD to get an A, it’s just that you’ve got to put in a good chunk of work, and people usually just decide to settle for a B. But sure, if you insist…

Straight talk. One of my earliest discoveries as a sixth grade teacher was that the vast majority of the students in my charge had literally never been told that their work wasn’t good enough.

By that, I don’t mean that they’d never received critical feedback. I just mean that they’d never heard the phrase “Sorry, this is unacceptable—try again.” Instead, they had spent years being treated with kid gloves, their constructive criticism sandwiched between compliments, their off-track ideas validated and praised so much that, at the end of a critique, they either didn’t even realize they’d been told to change course, or didn’t understand why.

This bending-over-backwards on behalf of kids’ emotional safety is corrosive in multiple domains. It atrophies their ability to handle adversity and regulate their own responses to unpleasant situations. It erodes the line between high-quality and low-quality work, to the point that some students no longer think it exists, or at the very least are unable to identify it themselves. Most importantly, it causes the average kid to think of adults as idiots, and the more perceptive ones to (correctly) classify them as “people who won’t tell me the truth.”

The antagonistic teacher makes a deliberate effort to subvert this paradigm, speaking to her students as human beings and near-equals. She draws a clear line between what work and behavior is acceptable and what work and behavior is not, and she is not bashful about identifying publicly which is which. This is always done with a core of unconditional high regard, but without undue softening—the phrase “You guys are definitely not dumb, so why are you acting like it?” is one that I uttered several times during each of my three years as a sixth grade teacher. She also seeks to be candid in other ways—for instance, when my students would complain that a particular activity or project felt utterly useless, I wouldn’t try to justify its relevance to their adult lives the way many of my colleagues would. Instead, I would simply shrug, and agree with them, and challenge them to find meaning and value in it anyway:

If you have to turn in this stupid worksheet one way or the other, then you’ve got a couple of options. You can put in the absolute bare minimum of work, so that you can get it out of the way and get back to the rest of your life. Or you can use it for practice, and level up. A lot of the time, it’s not going to matter what you know or what you’ve done—what’s going to matter is whether you’re the type of person who can buckle down and get stuff done right, and that’s a skill you’ve got to work at. This worksheet might be dumb, but if you think of it as a warm-up for important stuff later, it doesn’t have to be a total waste of time.

Systems meant to be gamed. In traditional classrooms, rules are fuzzy things, and teachers tend to enforce their spirit rather than their letter. This allows for a certain degree of sanity and consistency, since clever students don’t really have the power to munchkin the system.

The antagonistic teacher, on the other hand, is a stickler for exactitude. If, in the process of responding to a challenge, a student finds a cheap way to win, the antagonistic teacher doesn’t cheat her out of her victory.

This applies not only to math worksheets, but to project rubrics, debate rules, behavioral expectations, and the broader circumstances of being-a-human-stuck-in-a-school (since the goal is to train students in ways of thinking that will make them happy, effective human beings no matter where they end up in life). A significant minority of the antagonistic teacher’s activities and norms are constructed with known loopholes, and his students are encouraged and rewarded for finding them; when they dig out others that he did not put there intentionally, he applauds them publicly for seeing what he did not.

This is crucial, because the antagonistic teacher will typically make things very hard for his students. There will be extremely high bars for success, challenges where even the question is unclear, choices where every option seems bad, time pressures and restricted resources, and deliberate misinformation. If the students are to respond to this with determination rather than despair, they have to believe that the rug will not be pulled out from under them—that if they are, in fact, clever and resourceful, those traits will matter (and that if they are not, that those traits are worth developing). Train your students to cheat intelligently from day one, and they will be formidable indeed by the time they leave your classroom.

Openly manipulative. The word “manipulative” is somewhat negatively charged, so bear with me as I describe an example. Once a week, my students participated in a teambuilding initiative—a challenge or puzzle that required active collaboration to solve. In one of the early ones, I divided the class into five groups, and handed each group a hula hoop.

Okay. There will be golf balls in this activity. You may carry at most two golf balls at a time—one in each hand, none in your pockets or bags. Your job is to put golf balls inside your hula hoop; at the end of the five minutes, the group or groups with the most balls inside the area defined by their hoop wins the prize. You may move your hoop into a corner or under a table or whatever, and you may try to guard it by standing in front of it, but you can’t ACTUALLY STOP people from taking the golf balls out of your hoop—any person may pick up any ball from any place at any time. You have ten seconds to form a strategy with your partners—GO!

After exactly ten seconds, or about the time it takes to read this sentence, I upended a bucket of golf balls in the center of the room, and let human nature take its course.

What happened next is pretty much exactly what you would expect. Frustrations rose, and then peaked; in the end, no group had any significant lead over any other and the final determination of victory was essentially random.

Interestingly enough, though, the problem of coordination has, in this case, a trivial solution: simply stack all five hoops in the center of the room, and work together to fill it. This is a solution that feels slightly cheaty/hacky (see above), and when I explained it to my students after the activity, they almost always reacted with glares and groans. It’s almost too cute.

The manipulation comes in at the point where I refuse to give them sufficient time to come up with this solution themselves. I had other activities which similarly locally incentivized behavior that was globally counterproductive, or which contained instructions that strongly implied and encouraged false conclusions without ever stating them outright, or which pattern-matched to competition despite actually being better solved through cooperation. One of my favorite manipulations was to wait until I heard the correct solution spoken out loud, and then immediately distract the group by calling their attention elsewhere.

This is where the bulk of the actual “antagonism” in antagonistic learning comes in. In the manner of an adult playing peekaboo with an infant, I helped my students improve as rational agents by repeatedly exposing them to the flaws in their current models. I did not hide these manipulations; we often talked about them explicitly in debriefs, and whenever my students caught one ahead of schedule, I responded with a grin and a small reward. Eventually, it was taken as a given that, within the confines of a particular challenge or activity, I was Not To Be Trusted and the incentives were likely to be misaligned. I knew that I had fostered growth when, after blindfolding my students and telling them that they had to form the loop of rope they were all holding into a square, I heard the following:

WAIT. Before we all start talking, we should check to make sure that there’s actually just one rope.

Not here to make friends. One of the things I did every summer was pore over the yearbook from the previous year, memorizing all of the names and faces of my upcoming students.

This is a fairly common trick among teachers. There’s a lot of power in a name, and you get some fairly startled looks on day one from kids who aren’t quite sure how you know who they are. Many of my colleagues used this method to signal caring and warmth—it was a visceral way of demonstrating, right from the start, that they were willing to put in the work to build deep and genuine relationships.

In my classroom, however, there were no Hals or Lexies or Brysons or Dakotas—not at first, anyway. I began my first roll call with “Mr. Alvarez,” and carried it right through to “Ms. Yates.”

It wasn’t until halfway through October that “Mr. Green” became “Alex,” when he made a particularly insightful comment in a class discussion on the Catholic seven virtues. I drew no particular attention to the change, as I drew no particular attention to Mikayla or Darith or Johnny or Sam. Different classes caught on at different times; occasionally a student would ask about the discrepancy, and I would sidestep the question.

The point—which perhaps none of my students understood explicitly, but which lay behind this and other classroom norms—was that we were all there for a reason, and that that reason was independent of any particular sense of friendship or camaraderie. Respect was indispensable. Trust—insofar as my tricks and traps were known and known to be instrumental—was essential. Fairness, accommodation, discipline, compassion—these things were all necessary ingredients of a successful student-teacher relationship.

But warmth—warmth was a bonus. I used it as I used every other incentive—carefully, deliberately, and in pursuit of the overall goal. I like kids—middle schoolers especially; they are a fascinating mix of enthusiasm, irreverence, ambition, and skepticism. Generally speaking, I’m inclined to make friends, even if the human I’m talking to happens to be twelve. But too much warmth, too soon would undermine the hard lessons I intended to teach, and too little later on provided a spur to those who really wanted that one extra iota of public recognition. Every student had my default respect, but only the ones who were really, truly trying got to see me sit up and take notice.

The list above is not complete; there are thousands upon thousands more words to be spilled over the concept of antagonistic learning. What I’ve written so far is a rough and incomplete description, wrong in many particulars though approximately correct in the aggregate. If you find yourself startled or dismayed at some particular brush stroke, take a step back, and see if it makes sense when you squint; what matters here is not any one specific piece, but the overall picture.

Of course, it may be that you find the overall picture distasteful. Certainly I’ve met few other teachers who’ve chosen this particular philosophy, and I received no small number of complaints from students and parents alike (though curiously never from the parents of those upset students, nor the children of those upset parents). As always, I make no claim that my outlook and methods are correct in any universal sense—only that they worked, at least once, and well enough that I saw most of my students change for the better.

I’ll revisit many of these themes in my later EDUC posts, but for now, it’s time to zoom back in and start talking specifics. The next installment (which may not appear for a month or so; things are busy3) will be ground-level. I’m going to talk about Core Connections as an ideal, and how it was operationalized into specific lessons on critical thinking, project process, and collaboration. In the meantime, thanks for reading, and may you have fond memories of the grumpy old wizards from your educational past.

I’m perfectly comfortable with people who say that all kids are precious and wonderful, as long as they also say that all adults are precious and wonderful, too. You have to be consistent—anyone who doesn’t think an eleven-year-old can be a total snake either doesn’t think snakes exist or is willfully misremembering junior high. I’m also aware of the fact that people can change for the better, and that it’s my job to teach them well whether I like them or not.

Alternative explanation: the sense of engagement comes less from an increase in perceived value, and more from the fact that barriers are fun to overcome. The key is to create barriers of the correct height—difficult enough that students can feel pride when they finally overcome them, but not so large that students are too discouraged to try.

lolllllll

> I even had students attempt to buy additional questions off me by volunteering to sit out at recess—I’ll let you draw your own conclusions as to my likely response.

My model of you rejects, possibly explaining that there's nothing in it for you for the kid to be sitting out at recess. And if the offer was phrased as a question - "can I buy?" rather than "I'd like to buy" - then it counts as their question.

> If, in the process of responding to a challenge, a student finds a cheap way to win, the antagonistic teacher doesn’t cheat her out of her victory.

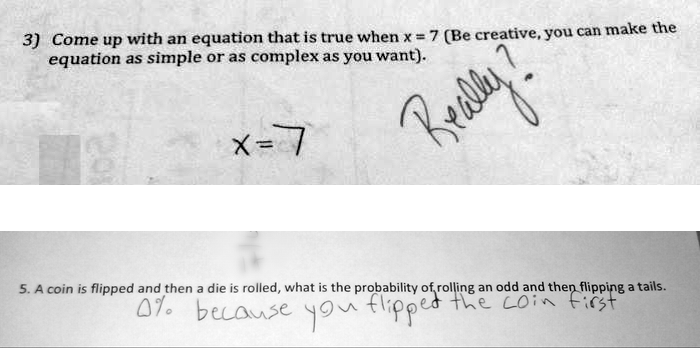

In the first image, I take it that you're pointing here at the answer as being totally legit, and [what I take to be] the teacher's "really?" is something you'd consider harmful?

> Openly manipulative

Vague memory from scounts (I would have been 13ish): we were in two teams at one end of the hall, tables at the other end, with stacks of doormats. We had to get a tennis ball under our table without touching the floor. Straightforward enough. (My guess is it was somehow more complicated than this.)

Then the mats were taken away. "Okay, now get the balls under the table." I thought to lasso the table and pull it towards us, while the other team tried to make a long stick to push it. It came pretty close to a draw, because lassoing turned out to be harder than I expected; and also because after our first success, one of the scoutmasters took it off saying that was cheating or something, and then another scoutmaster said "nah it's fine" but no one put it back for us. I don't remember if we asked, and I think I'm not a fan of this detail in hindsight.

And at the end, they pointed out that they hadn't said "no touching the floor" for this one, and we could have just walked across the room.

Another occasion where we had to pass a small beanbag between us. Easy. "Now do it without touching it with your hands." Fine. "No elbows." "No chins." "No mouths." Eventually they pointed out a solution we'd missed: drop it into a bucket and pass that around.

Do you have examples of "children left behind"? If so, did you notice patterns? If so, do you have ideas for a different environment which a different person could implement well which would help them thrive (while leaving behind others, presumably)? Do you know anyone personally who you predict would not have thrived, as a child, in your environment?