Part three in my ongoing series Five-Hour Drive, about places and experiences that I’ve found are worth going (at least) five hours out of my way for. The previous two entries are about Hartzell’s Ice Cream in Bloomington, Indiana, and Compression Falls on the TN/NC border.

I.

There were things that happened before, and there were things that happened after, but I think the right and proper place to begin this particular story is here:

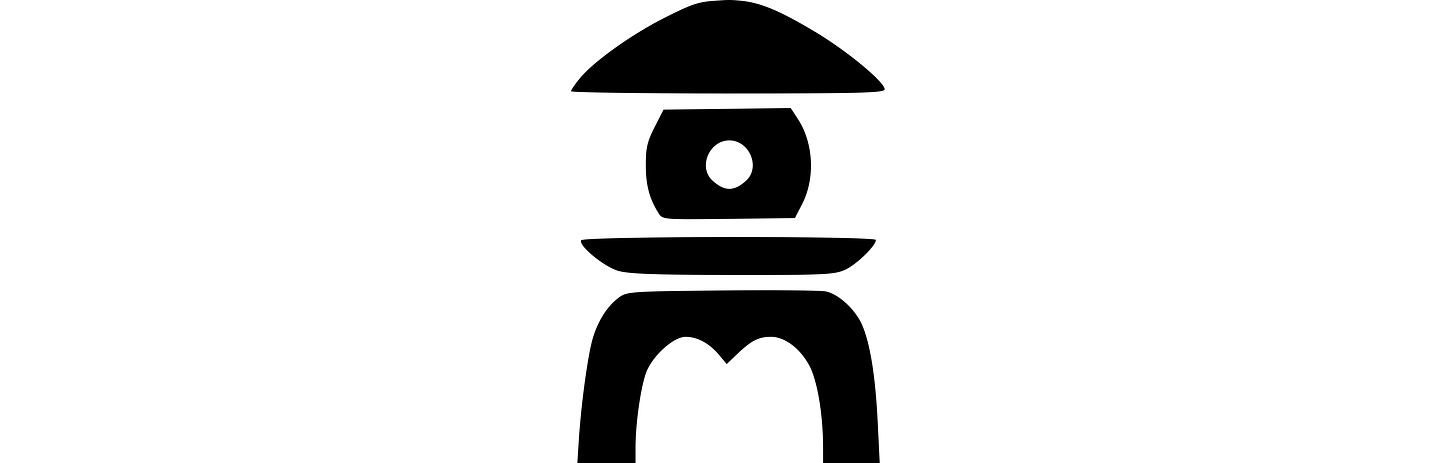

I took this picture on Friday, March 10th, 2023, at 11:32AM, in the Umami Café, which sits overlooking a gentle hillside in the Portland Japanese Garden.

The reason I took the picture is because I knew that I wanted to own a copy of the object, and it had no identifying marks of any kind, and the staff at the café didn’t know what it was called or where it had been purchased. My hope was that my extended social network might be able to aid in the search.

You may perhaps already know exactly what this object is. But even if you do, you presumably once encountered it for the first time, and with a little effort, you might be able to reconnect with what it was like to go from not-knowing to “oh!”

You might be able to imagine sitting down in an elegant, austere tea shop and wondering what, exactly, was going on with this strange little thing in the corner of the spread.

(This is your chance to pause and ponder, should you so desire; the short video after the next image will Give Away The Secret.)

I did eventually procure my own, slightly larger version, which I use at home when putting on chocolate tastings:

(If for some reason you can’t see the video: you drop the little white pill-shaped object into the deeper well on the side, which is filled with hot water, often scented. The pill swells up and expands, absorbing all of the water, and you unroll it into a warm moist towelette.)

There is something about this which absolutely delights me. I am delighted by the particular feel of the napkin on my skin. I am delighted by the process of dropping the tablet in, watching it rise and swell. I am delighted by the aesthetic of the napkin-holder itself—the elegant design, the ritual, the way it guides me forward, hints at what I am supposed to do. I am delighted that someone somewhere in the past caused all of this to happen—that some quiet visionary conceived of this moment, and reached into the future to arrange this experience for me. Someone took the small, mundane action of wiping my hands mid-meal and elaborated upon it, transformed it into a thing of quiet, simple beauty. I feel seen, and cared-for, expertly held.

I can imagine my way into a sort of dour, disdainful but why? mentality, in which the whole thing seems silly, excessive, ostentatious, why wouldn’t you just use a regular disposable wetnap, why all this rigamarole…

…but…

…but isn’t this better?

Isn’t it clearly better, isn’t it viscerally better? In one world, you’ve done a magical ritual with a beautiful object. In the other, you’ve ripped open an ugly pouch with a bunch of words printed on it and now you have a piece of crumpled trash sitting next to your teacup.

Okay, fine, my inner Scrooge grumbles. Then put out a nice little insulated bowl that’s full of warm wetnaps and just pull one out when you’re ready.

That…is better, I admit. Better than simple napkins, I mean, better than regular wetnaps. Better in the same sort of way as what they do in the Umami Café.

But even so, I can’t help visualizing buffet food drying out under heat lamps, something made warm too soon and kept warm too long, something that didn’t have a proper moment. In the café, the tiny wells stand empty until the food arrives—only then does the waiter fill them, expertly, from a steaming kettle, without spilling a drop, such that by the time I do want to wipe my hands, the water is the perfect temperature, warm without being scalding. The whole thing is precise and ceremonial and reverent in a way that is conspicuously missing from most of American life. There’s a weight to it, a calm deliberateness, a sense of things taken seriously and done correspondingly well. Of attention to detail—loving attention to detail, rather than resentful, dutiful, mercenary attention. Someone did all of this on purpose, and not because they had to.

Because it was better.

When I try my best to adopt the but why perspective, and feel my way into a sort of dismissive impatience, what I notice most is a feeling of scarcity. I get a sense of something like “but don’t we have better things to do with our time and our money?”

And honestly, I agree that we do. I certainly can’t afford to pour this much love and artistry into every small, mundane task. I can’t make brushing my teeth and trimming my nails and tying my shoes and folding my laundry and feeding my cat and opening my laptop and checking my email beautiful in this way.

But I wish that I could. I wish that every aspect of my life could be clean and lovely and purposeful and perfect.

And the fact that I can’t make every part of life that way doesn’t seem like I shouldn’t make any part of life that way. I agree with my inner Scrooge that there’s something arbitrary and unfair about choosing this particular thing over all those other things, but…

That feels like it’s setting the bar too high, or something? Like insisting that I justify which thing I make perfect would ultimately result in me never choosing anything.

(Because there’s always something else competing for my attention. There’s never a shortage of reasons to draw the line at “okay, this is good enough” and switch over to working on the next thing.)

And sometimes—

(I claim.)

—it’s better to concentrate one’s efforts. Even if there isn’t a principled argument for it. Even if the choice of here and now is arbitrary. Even if there are, technically, more important things. Even if the surrounding moments suffer somewhat, as a result of me putting “too much” in the “wrong” place.

I feel something like … this is a somewhat clunky metaphor, but “I’ve only got so much white paint to spread around on this black canvas, and if I try to spread it evenly and fairly and justifiably, I’ll basically end up with a uniform very-dark-gray canvas.”

Which does not seem as worthwhile, to me, as a painting of the stars.

II.

The day that I visited the Portland Japanese Garden was not “beautiful” in the traditional sense. It was a cold, wet, gray morning in March.

The leaves drooped. The rocks and steps were slick with rain. The sun didn’t make an appearance until we were already on our way out.

I was traveling with my spouse, Logan, who was six months pregnant; we had gone to Seattle to spend a week together on a belated honeymoon, and were stopping in Portland on our way home.

We didn’t have a ton of time. Logan wasn’t particularly comfortable. It was not really the right time to linger.

Nevertheless, we lingered.

We walked slowly, awestruck, through the Nezu Gate, over the Moon Bridge, past the Strolling Pond Garden to the Heavenly Falls.

We took the one-way path down through the Natural Garden, passing under the Moon Gate and ending at the quietly breathtaking Sand and Stone Garden, whose plaque explained the relationship between the current display and the Jataka Sutra, in which the Buddha risks death to save a starving tigress and her cubs, trapped in a ravine.

We walked back up the hill, past the gorgeous Flat Garden and back to the Nezu Gate…

…where we realized that we weren’t finished, not even close, and we went back for more.

It may be that your eyes are glazing over a bit, by this point—there are only so many photos of soft, verdant beauty that a person can consume before they all start to blur together, and I’ve already shown you close to a dozen in a row.

That’s okay. But I’d like to start showing you pictures with a bit more of a purpose than just “oooh, look how pretty!” There are lots and lots of places in the world that are pretty. The thing that makes the Portland Japanese Garden special is something else.

Take this tree, for example:

This tree requires support, to grow in the way that it’s been shaped to grow.

Any sort of support would do. When I imagine a similar tree in a normal American park or garden, it’s easy to visualize metal pipes or 2x4s, steel cable strung to nearby pines—there are lots of different ways to get the job done.

But here—as with the napkin holder—the job hasn’t simply been done. It’s been done well.

It’s been done beautifully.

The supports are not an afterthought. They’re not treated as separate from the beauty of the tree, and the bushes, and the moss, and the stone lake. They aren’t held to a different, lower standard. Someone took the time to include the supports in their thinking and planning, to make them beautiful in their role as a part of the garden. There is no excuse-making, no settling, no disregard.

This is true of the entire garden.

Everywhere you turn, there are utilitarian elements, things that are there because they have to be there, scaffolds and guard rails and pipes and drains.

And everywhere, those elements have been transformed, elevated, respected. Not one single square meter of the garden has been treated carelessly, left at “good enough.”

It’s not that the perfection is stifling, either. There’s such a thing as too perfect—too clean, too crisp, too precise. You can make a garden that is so neat and orderly that it feels harsh, alien, unwelcoming—not a place for humans, not a place for life.

But no. The Portland Japanese Garden has imperfections aplenty. It has leaves and twigs out of place. It’s simply that the leaves and twigs are out of place in the places where leaves and twigs should be.

(I’m probably not explaining this very well. I’m sorry. It has something to do with rightness. The phrase that keeps cycling through my mind, over and over, is just so.)

The Portland Japanese Garden is just so. Everything in it is just so. When I am in it, I feel what it’s like for everything to be just so.

And that’s a big deal, for me.

III.

I have autism.

I discovered this fact rather late in life—just a few years ago, with a lot of help from Logan, who had the same epiphany a year or two before me. A fun and semiregular activity these days is dredging up some memory, some story I’ve told a hundred times, and pausing to reassess it in light of my new self-awareness and going “…oh. Right.”

One of the ways that I have … metabolized? Expressed? Coped-with? …one of the ways that my autism has manifested itself throughout my life is via a sort of sensitivity to wrongness.

By “wrongness” I don’t necessarily mean something like injustice (although I, like many neurodivergent people, do get rather heatedly outraged at things that seem to me to be unfair or unjust).

No—it’s more like a sensitivity to archetypes, patterns, Platonic ideals. I often have a very strong sense of what is supposed to be happening, how things ought to go, what something is trying to be, and then the glaring, conspicuous deviations from that are difficult for me to tolerate.

For instance—

(This will be a digression. Hopefully it’s an illuminating one.)

—in the 2003 film The Last Samurai, which depicts a romanticized version of the Satsuma Rebellion, the character of Nathan Algren (portrayed by Tom Cruise) has been captured by the samurai leader Moritsugu Katsumoto (played by Ken Watanabe) and taken up into a village deep within the mountains, where he is eventually won over.

The samurai of Katsumoto’s faction are violently resisting the modernization of Japan, which includes the removal of samurai-in-general from their previous lofty position of social power. About three-quarters of the way through the movie, Katsumoto and a small group of his followers and advisors are granted safe passage into the capital, to parlay with the Emperor.

When they arrive, anti-samurai sentiment in the capital is at its peak. Katanas have been outlawed. Samurai regalia has been outlawed. It’s clear that the police (many of whom were commoners who would have been oppressed and abused under the old system) have been taking revenge left and right. Katsumoto’s party kinda-sorta has immunity, in that they’re technically there at the Emperor’s invitation, but they don’t have a formal escort and there isn’t really any way for them to complain if Bad Things Happen.

At one point, Katsumoto’s son, Nobutada, is walking the streets by himself and ends up surrounded by something like eight hostile cops, all carrying rifles. They’re jeering at him and mocking him and spitting on him, demanding that he give up his sword. He’s mostly taking it stoically, quietly refusing to comply, but then they all point their rifles directly at him, and Nathan, who’s nearby, tries to intervene.

They point their guns at him. One of them knocks him to the ground. Nobutada, who hadn’t lifted a finger in his own defense, goes to draw his sword, but Nathan stops him, preventing him from (essentially) committing suicide by cop.

And then, in a quick but devastating scene, the cops take his sword and saw off his topknot and knock him down and leave him dirty and humiliated in the middle of the muddy street. He and Nathan get up, and they walk off together, and the movie just … moves on. There’s no discussion, no exposition. We know what it all means, because we’ve been learning about Nobutada’s culture alongside Nathan. We understand how hard it hurts, how thoroughly he’s been dishonored. Nothing more needs to be said.

And it kills me every time, because you see, you see, you see, the whole point of Nathan Algren’s arc is that he’s falling in love with a way of life. It’s not about personal loyalty, specific interpersonal connections. Yes, he cares deeply for the people of Katsumoto’s village, but that’s not what’s driving him. He’s essentially been converting to bushido as if it were a religion, reinventing himself as a man of strength and honor where before he was a broken-down alcoholic wreck trying (and failing) to outrun his PTSD.

And from a thematic and narrative standpoint, it’s a betrayal of all that to make the whole scene be about him just … standing up for a buddy. We already know that Nathan stands up for his buddies. It’s been shown multiple times in the film so far.

Imagine instead the version of the scene where, instead of being the man whose house he’s been living in for the past four months (inexplicably separated from his father and the rest of the delegation), it’s some random, nameless samurai that Nathan comes across after he’s turned loose in the city. Let everything play out in the exact same way, except instead of Nathan being motivated by personal loyalty, he’s motivated by a feeling of fraternity. An old-school samurai, looking very much like the men who’ve spent the winter rehabilitating him, is being tormented and threatened by eight men dressed in precisely the Western garb he’s come to revile. He steps in, compelled by his newfound sense of honor and responsibility. He’s knocked to the ground, disrespected, and the samurai who had been tolerating the abuse being hurled at him is suddenly ready to die in defense of a stranger who came to his aid—except Nathan stops him, saves him, does not let him throw his life away.

(And then, after it’s all over, they walk away together, Nathan attempting to comfort the other man in his broken Japanese.)

It’s far, far more elegant, far more powerful, more in line with the story that the movie is trying to tell. It’s clearly what was supposed to happen, what should have happened.

And they just … missed it. Wasted it. Passed over the opportunity to make something great, and settled for something that was fine, I guess.

This is the sort of thing I mean by the phrase sensitivity-to-wrongness. I saw The Last Samurai twenty years ago, and I’m still not done being bothered about it.

I’ve mostly managed to hammer this sword into a plowshare. This particular OCD-esque psychic vulnerability is actually a huge part of what’s made me a good writer, a good teacher, a good workshop lead, a good student of human nature. If you scroll back through my essays, you can see that most of them are pearls formed around some seed of frustration, something that shouldn’t be this way, it could be better, it should be better.

(And sometimes, when I write about it, it gets better.)

You can get pretty far in life being able to identify more problems than the people around you, even if that doesn’t always necessarily translate into understanding the solutions. But the thing about taking a disability and converting it into a strength is that it’s, uh. It’s still a disability?

“Being autistically irritated” is pretty mild, as disabilities go. I wouldn’t trade my problems away for most people’s problems.

But the emotion, the fire, the sheer grrrrr that I tried to give you a glimpse of, above … that feeling sort of dominates my life. It’s nearly omnipresent. I look around my room, and there are things that are wrong (I’m mostly single-parenting a toddler and I just cannot stay ahead of the chaos). I go out onto my property, and there are things that are wrong. I get in the car and turn on the news and it’s wrong, I pick up the phone and call my mom and there’s so much wrong, I’m just surrounded by it and it basically never lets up.

(I go onto a website called LessWrong, hoping to find solidarity and fellowship, hoping to find a community full of people who get it, who actually care about the wrongness, and instead I find a whole lot of talk and a, like, 2% reduction in the normal background rate of wrong, wrong, wrong. Which, hey, a 2% reduction would be worth celebrating in most cases, but it’s kind of a letdown for a place that literally named itself LessWrong, y’know? It hurts. I leave.)

And the reason I’m telling you all of this is so that you will understand what it means to me when I say that there is absolutely nothing wrong in the Portland Japanese Garden.

(Well. I mean. There were some visitors there who were doing it wrong, but mostly I was able to just walk away from them and wait for them to leave and it was okay.)

But the garden itself—

It’s not that I want to notice wrongnesses, everywhere I go. I often wish I could turn it off, just like my spouse Logan wishes he could turn off his auditory sensitivity, go temporarily deaf at will.

But I’ve been trained, traumatized, sensitized into pre-flinching basically at all times, expecting that every time I shift my eyes there’ll be something. I go down to the creek on my own property, which you might expect to be in a sort of natural equilibrium with no wrongness, but no, there are invasive plants and there are the scars of previous landscaping and there’s this ugly, frayed yellow rope strung across the water and there’s built-up debris from dead trees that probably should have burned away except that California doesn’t let the fires run through and so the fuel just builds up and builds up and then when the fires do come they’re worse—

But it’s simply not like that, in the Portland Japanese Garden. I almost couldn’t believe it. I’d been unconsciously expecting the opposite, anticipating an experience full of tiny flinches. It was the first time I’d ever been taken by surprise by an absence of horrible flaws.

(Again, it’s not that it’s perfect, but rather that its imperfections are balanced, proper, good. Like a mole on the face of a person you deeply adore. It’s a right kind of flawed.)

I don’t know how much of this property has to do with the garden’s inherent Japanese-ness. I do get the sense that the Japanese cultural tradition cares more about excellence and perfection and balance than the Western one does, but it’s not the case that every Japanese garden gives me this same feeling of relief. The Hagiwara garden in San Francisco, for instance, is amazing and tranquil and lovely and is the sort of place I will visit every time I happen to be in the city—

—but I won’t go five hours out of my way just to visit it. The Hagiwara garden does not have a gravel ring around each building, placed just so beneath the overhanging eaves, to quietly catch the water as it drips from the roof and make the paving stones less slippery on drab, gray mornings in early March.

It doesn’t contain a scale model of its own grounds, rendered in loving detail, with even the trees placed accurately (as far as I was able to tell).

It does not have a wildness that somehow manages to feel sane and organized, a tameness that somehow manages to feel alive and natural, an actual balance that feels worthy of something like worship (as opposed to something merely beautiful that’s worth admiring without being particularly moved).

And I don’t know. It may be that all of that means that it’s not for you. It may be that you, lacking my flaws, lacking the particular need that I have, wouldn’t actually find that it’s worth going five hours out of your way for.

But I felt a peace in the Portland Japanese Garden that I honestly don’t think I’ve ever felt before. I relaxed muscles, both literal and metaphorical, that felt as though they’d been holding tension for thirty-six-and-a-half years.

And I know, because someone built the Portland Japanese Garden, because there are whole teams of people who tend and maintain it and keep it just so—

I know that I’m not alone. Not just in the generic sense that sure, yeah, there must be other people like me out there somewhere, but in the very extremely specific sense of oh, someone who doesn’t even know I exist made something that fits me perfectly.

Which means that they see it. They get it. They understand.

I move through the world constantly surrounded by evidence that approximately everyone around me doesn’t. Constantly confronted by visceral proof that most people are not my people, most people don’t care (about the same things that I care about), basically no one else is trying (in quite the same way that I try).

But the Portland Japanese Garden was different. It was irrefutable evidence to the contrary, a straightforward demonstration that I’m not the only one. And even though I did not actually get to meet any of my fellow tribesmen, I passed through their sanctuary, and felt the whisper of their presence, and that, too, was healing.

I cannot wait to go back.

This was satisfying to read. Even though I suspect the *specific* forms of wrongness you're most sensitive to have only moderate overlap with the ones I'm most sensitive to, the *general* idea of being almost-constantly surrounded by things-one-finds-wrong is very relatable to me, and it was satisfying to read about the details of this place being such a healing surprise to your constant expectation of wrongness.

Also, I feel like I now have a better understanding of what you mean when you identify with MTG-Green. In the MTG essay, I remember being surprised that you described yourself as mostly Blue/Green. Had you not included that detail, I would have thought (based on other things you've written) that you're primarily Blue, with White and Red not far behind in a close race for 2nd/3rd, and with Green as a more distant 4th. But this essay is simultaneously very MTG-Green AND very Duncan Sabien, such that those two concepts now feel like that fit together in my mind much more easily than they did before.