Deadly by Default

A primer on existential risk from artificial intelligence (8000 words/25-45min)

There is a lot of material out there on AI safety, and the dangers of strong AGI.

A lot of material. Scattered all over, in various places, much of it layered and highly technical. I don’t actually know of any short, simple, standalone documents that just…lay out the case for concern, from start to finish, in language that a smart high-schooler could follow.

So here, in case anyone else finds it useful, is my attempt to describe the trap, as I see it. These are the dynamics and incentives that seem to me to add up to “outlook not so good.”

Note: while I work for an organization that has stake in this sphere (the Machine Intelligence Research Institute), this is my own take and does not necessarily represent the opinions or beliefs of my colleagues or superiors.

1. The explicit target of many modern AI developers is superintelligence.

There are truckloads of money to be found in things like replacing cashiers with kiosks and law clerks with LLMs, or deploying systems like AlphaFold which revolutionize entire industries.

However, for people like Sam Altman and Demis Hassabis and Yann LeCun, those truckloads of money are not the point. They’re merely a means to an end. Modern AI developers are not, for the most part, trying to automate various jobs or solve specific problems—many of them are hoping to build a single, incredibly powerful system that can be deployed on any task, faster and more effectively than the entire human economy.

You and I do not know how to accomplish tasks like:

Cure all cancers, and figure out how to stop or reverse the effects of aging so we can live as long as we like

Eliminate pollution, clean up the environment, and control the climate without sacrificing our ability to travel freely and make whatever we want

End all war and conflict in a way that leaves literally everyone happy and content and fulfilled

Develop the bioengineering capacity, materials science, and nanotech that will unlock activities like “invent an entirely new creature” or “build a spaceship that costs less than a car” or “terraform other planets”

(Let alone the wilder and more ambitious goals that we haven’t even thought of, but an AI that was properly on our side would, just as we create positive experiences for our pets and our young children that they would never think to ask for.)

But these tasks are within the reach of science, given sufficient time for research and development. All of the power that humanity currently wields comes as a result of scientific inquiry (and subsequent engineering based on scientific discovery). You could think of AI development as a method of automating and accelerating the process of scientific inquiry, building systems which can absorb and synthesize all existing knowledge, identify promising lines of investigation, and carry out those investigations at top speed, thoroughly and without error.

(Including investigations into how to be better at this whole process.)

A superintelligent system that can compress hundreds or thousands of years of human effort into an afternoon would be able to just … tell us which actions to take, to bring about any arbitrary possible goal. And that’s the kind of system that Altman et al are explicitly seeking to create.

This is my answer to the common objection “But AIs just aren’t powerful enough to pose a threat.” That’s true of today’s systems, but developers are not stopping at today’s systems, which will likely bear the same relationship to tomorrow’s systems that the Wright Brothers’ plane bears to an F-35.

2. Every step on the path to a superintelligence makes you (lots of) money.

A strong system is one that can handle more complex and difficult problems. A general system is one that can be deployed on a wide range of tasks, as opposed to needing to be custom-built for one specific purpose.

Current AI systems aren’t all that strong, and they aren’t all that general (and they’re pretty expensive to run, although they’re more cost effective than human labor for a growing range of tasks). But every time a researcher comes up with a way to make an existing system stronger, or more general (or cheaper/more efficient), they, uh. They make a billion dollars.

(Not literally, but that’s the gist of the situation.)

At every step of development, taking your system and making it more powerful lets you apply it to problems at a new level of difficulty. This opens up new markets, and lets you make more money.

At every step of development, taking your system and making it more flexible lets you use it and sell it in more domains. This opens up new markets, and lets you make more money.

At every step of development, taking your system and finding a way to run it more cheaply lets you sell it to more people, which again opens up new markets and makes you more money.

There’s essentially always more money waiting out there, for someone with a better AI. There are always people who are looking at today’s AI and thinking hmmm, this doesn’t quite do what I need it to do but it’s getting closer. Investors want in, and doctors and scientists and politicians and generals and hedge fund managers who see the potential want to be able to whisper in the ear of the developers, and their desire to influence the shape of the future system means that the developers get to whisper back.

(Not to mention the fact that, as more and more of the economy comes to depend on AI, the people controlling it become the people that are keeping the planes in the air and the medical research going and so on and so forth.)

All of which means that, on any given day, there’s a strong incentive for researchers and engineers to keep going, as quickly as they can. Each new step forward rewards them with piles of money and the attention and respect of powerful people who will send them more money if they can figure out the next step.

There is no end point. There’s no “enough is enough.” No matter how rich you are, and no matter how cool the system of today is, the system of tomorrow is even cooler and future!you can be even richer. And if you don’t take that next step, then there’s usually someone else who will. It’s akin to an arms race—the way the incentives line up, somebody is always going to be interested in paying for an Even Smarter And More Powerful Thing, no matter how smart and powerful the thing we’ve already got is.

(For instance, Bill Gates is investing in nuclear power plants, because it takes nuclear power plants to provide enough energy to fuel the systems he expects people to build over the next couple of decades, and he expects this investment to pay off.)

This is my answer to the common objection “But we’ll just stop before we build anything dangerous.” The people actually doing the building are overwhelmingly incentivized to both say and actually believe that it’s fine, it’s not dangerous yet, let us keep going, it’s too early to slow down, look how much money we can still make and look at all the good we can still do.

c.f. Upton Sinclair’s “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it,” except in this case it’s not only salary but also the allure of curing cancer and ending war and controlling the global economy. Expecting someone in that position to correctly identify a safe stopping point with an adequate margin of error is unwise; humans are really good at rationalization when properly motivated.

3. The smarter the agent, the more complex its plans.

I’ve previously found it useful to think of intelligence as being made up of three parts:

The ability to perceive the world around you, and gather data from it

The ability to analyze/interpret/comprehend the data that you’ve gathered

The ability to turn that understanding into effective action, through feasible plans.

An agent that sees more of the world around it has more knobs and levers to work with, more pieces it can take into account and possibly rearrange.

An agent that understands those pieces more thoroughly can more effectively use what it has at hand (like how ravens in scientific studies frequently bend bits of wire into tools, while chickens do not).

And an agent that can juggle combinatoric complexity and think three or four or five steps ahead can accomplish things that an agent who can only think one or two steps ahead can’t.

Dogs want delicious food and interesting toys, but it’s humans that have built up the supply chains and manufacturing capacity to bring that food and those toys into existence. It wouldn’t occur to a dog that the solution to something like an upset tummy might perhaps route through a vast and branching tech tree that involves antibiotics derived from Amazonian fungus and scalpels made of German steel and microscopes designed in Japan—but humans who wanted their dogs to feel good invented veterinary medicine and have in fact reached that far to get the job done.

There’s the internal complexity of computation (which I’ll talk about more in a later section), but setting that aside, if you ask an artificial intelligence how to go about curing all cancer and it actually answers, that plan will almost certainly be extremely complex, and involve assembling all sorts of apparently-unrelated bits of reality in a pretty particular order.

Importantly: since the whole point of a superintelligence is that it sees and understands reality far better than we do, and can reach much further afield to find the best solutions to various problems, we will not be able to follow and comprehend its strategies. A chess novice does not understand why a chess grandmaster moved a particular piece. The world’s best Go players still don’t understand what AlphaZero is doing most of the time. Sure, we might be able to follow some of an AI’s strategic reasoning, especially if we ask it to explain it in language we’re capable of following. But on the whole, what the AI is for is the set of problems that are too complex for us to wrangle, and we should expect that many of its solutions will be as incomprehensible to us as the workings of the veterinary medical system and the global supply chain are to our dogs.

Or, in other words, at some point, we will switch over from “doing things because they make sense to us” to “doing things because the AI told us to and when we follow its instructions good things happen in unexpected ways.”

(Unexpected and by default inexplicable even after the fact.)

This is my answer to the common objection “But we’ll just … only listen to the AI if what it’s telling us makes sense.” People will very quickly stop waiting-until-the-instructions-make-sense when they notice that their competitors are not waiting, and are reaping huge rewards from blindly trusting the machine.

4. You have to give your superintelligence the information it needs to get the job done.

Imagine setting out to have some major impact on the current geopolitical situation, without knowing anything about the personalities and histories of people like Xi Jinping or Vladimir Putin or Donald Trump.

Imagine trying to understand generational differences in health and behavior without being told about the impact of leaded gasoline on Boomers or microplastics on GenZ.

Imagine a dog confidently telling you that you don’t need to know about geology and paleobiology and the distribution of petroleum underground, because that has nothing to do with giving that dog tasty food and interesting toys.

If you’re trying to build a system that can tell you how to solve climate change, it needs to understand everything. It needs to know about the weather, the geography, the economy, politics, all of it. Every bit of information you withhold from it just makes its model of the world coarser and less powerful, which means that its plans are less tuned and more likely to fail.

If you want your superintelligence to understand the world in sufficient detail to see the quickest and cheapest and most efficacious solutions—to see the stuff that you can’t, make the leaps and connections that no human would ever make—then you can’t blind and cripple it. Its ability to do what you ask of it is directly proportional to its ability to see the entire gameboard, access every individual thread.

The systems with less access to information will underperform, and the systems with more access to information will overperform. It’s another simple selection pressure, a straightforward incentive gradient, and it means that ultimately, somebody is going to make sure that their AI has access to all of the information.

This is my answer to the common objection “But we’ll just limit how much information it can access. We’ll only give it the information that’s relevant to the task at hand.” We don’t know what information is relevant to the task at hand, any more than a dog knows which bits of knowledge are relevant to the creation of canned food and squeaky toys. The people who are gunning for superintelligence are serious about goals like space colonization and human longevity, and they’re not going to handicap their own efforts to achieve those goals as quickly as possible.

5. Humans are a part of reality.

Not only are we a part of reality, we are a manipulable part of reality. Just look at how much money entities like Facebook pour into A/B testing and advertising, because those efforts pay off in terms of directing our behavior.

Any system which successfully models the world in sufficient detail to be able to make arbitrarily complex things happen—

(and remember, there are billions and billions of dollars driving us forward toward that point, however far away from it we might be right now)

—must necessarily understand psychology and sociology well enough to predict and influence the behavior of humans, both individually and en masse, because humans are (at least presently) one of the most important factors in what-happens-on-Earth.

It’s not the case that the system necessarily has to have distinct mental buckets for “psychology” and “sociology” or even that it needs to “think” about humans in any clear, explicit sense. ChatGPT doesn’t “understand” humans in the way that you and I understand ourselves and each other, and yet it manages to predict human behavior passably well.

And (hopefully obviously) you don’t cure cancer or end war or reverse climate change without modeling humans, and without incorporating humans into your plan (which means understanding how to motivate and incentivize them, and knowing what sorts of things cause humans to give up or freak out or otherwise say “no”).

Put another way, an artificial intelligence which can’t deal with humans at least as deftly as the best politician/therapist/teacher/motivational speaker in the world clearly isn’t a superintelligence in the way we’re using the term, and thus if you have a proto-superintelligence that’s really good at everything except nudging the humans around, there’s infinite money on the table for the first person to develop one that is that good.

Even the blind, fumbling, nascent AI systems of 2024 are already good enough to replace the bottom half of therapists and life coaches, let alone copywriters. The systems that modern AI developers are explicitly trying to build will be superpersuasive, able to move humans around more deftly than we move around livestock.

This is my answer to common objections like “But an AI won’t be able to do anything without human help” and “But we’ll have human oversight to make sure nothing nefarious happens” and “But we just won’t let it have access to the internet.” The cancer-curing, war-ending, climate-repairing, spaceflight-enabling superintelligence must necessarily have access to all available information in order to do its job. A system that is smarter, more eloquent, and more persuasive than any human on earth and which also knows an awful lot about you specifically is not going to find you an obstacle to its aims.

6. We don’t actually know how to install goals or values into an artificial intelligence.

In point of fact, we actually don’t know how modern AI systems work at all.

I mean this in the literal, straightforward sense—there is no human on earth who can tell you what ChatGPT is doing, in the way that there are humans on earth who can tell you what your car engine is doing, or what SpaceX’s rockets are doing, or what the Large Hadron Collider is doing. The foremost experts in the world genuinely do not know what’s going on under the hood.

This is largely because modern AIs aren’t really designed so much as grown or evolved. They’re the result of a mix of randomness, selection pressure, and human tweaking. Currently, a very small percentage of AI scientists are engaged in interpretability research, meaning that they are studying existing systems in the same way that biologists study animals, trying to learn how their pieces fit together and what those pieces are doing. They’ve made some small, preliminary headway in understanding the internal workings of some of the current systems like Claude and ChatGPT.

But that work is fairly low-priority and vastly outpaced; it will be years if not decades before we have a thorough, mature understanding of today’s AI (if we ever manage it at all) and meanwhile tomorrow’s systems are already in development. Give it two or three years and not only will the cutting edge be substantially more complex, it may also be different enough that insights and intuitions gleaned from studying today’s systems won’t even transfer.

And (unfortunately, from our perspective) emergent, complex entities do not, by default, share the “goals” of the processes that gave rise to them.

When making an AI like Claude, approximately the best that we can do is to select the systems which output more-or-less desired behavior in the training and testing environments. We try everything, and then we cherry-pick the stuff that works.

(This is a little bit oversimplified, but that’s the gist—we don’t actually know how to make a large language model “want” to be nice to people, or avoid telling them how to build bombs. We just know that we can pick and prune and clone from the ones that just so happen to tend to be nicer and less terroristic.)

(And then put patches on them after the fact, when they’re released into the wild and people inevitably figure out how to get them to say the n-word anyway.)

There is no point in the process at which a programmer types in code that equals “give honest answers” or “distinguish cats from dogs” or “only take actions which are in accordance with human values.” There are simply tests which approximate those things, and systems which do better at passing the tests get iterated on and eventually released.

But this means that the inner structure of those systems—the rules they’re actually following, their hidden, opaque processes and algorithms—don’t actually match the intent of the programmers. I caution you not to take the following metaphor too far, because it can give you some false intuitions—

(Such as tricking you into thinking that the AI systems we’re talking about are necessarily self-aware and have conscious intent, which is not the case.)

—but it’s sort of like how parents and schools and churches and teams impose rules of behavior on their children, hoping that those rules will manage to convey some deeper underlying concepts like empathy or cooperation or piety…

…but in fact, many children simply work out how to appear compliant with the rules, on the surface, avoiding punishment while largely doing whatever they please when no one is looking, and developing their own internal value system that’s often unrelated or even directly contra the values being imposed on them from without. And then, once the children leave the “training environment” of childhood, they go out into the world and express their true values, which are often startlingly different despite those children having passed every test and inspection with flying colors.

The point here is not “AI systems are being actively deceptive” so much as it is “there are many, many, many different complex architectures that are consistent with behaving ‘properly’ in the training environment, and most of them don’t resemble the thing the programmers had in mind.” Any specific hoped-for goal or value is a very small target in a very large space, and there’s no extra magic that “helps” the system figure out what it’s “really” supposed to be doing. It’s not that the AI is trying to pass the test while actually being shaped rather differently than expected, it’s just that the only constraint on the AI’s shape is the tests. Everything else can mutate freely.

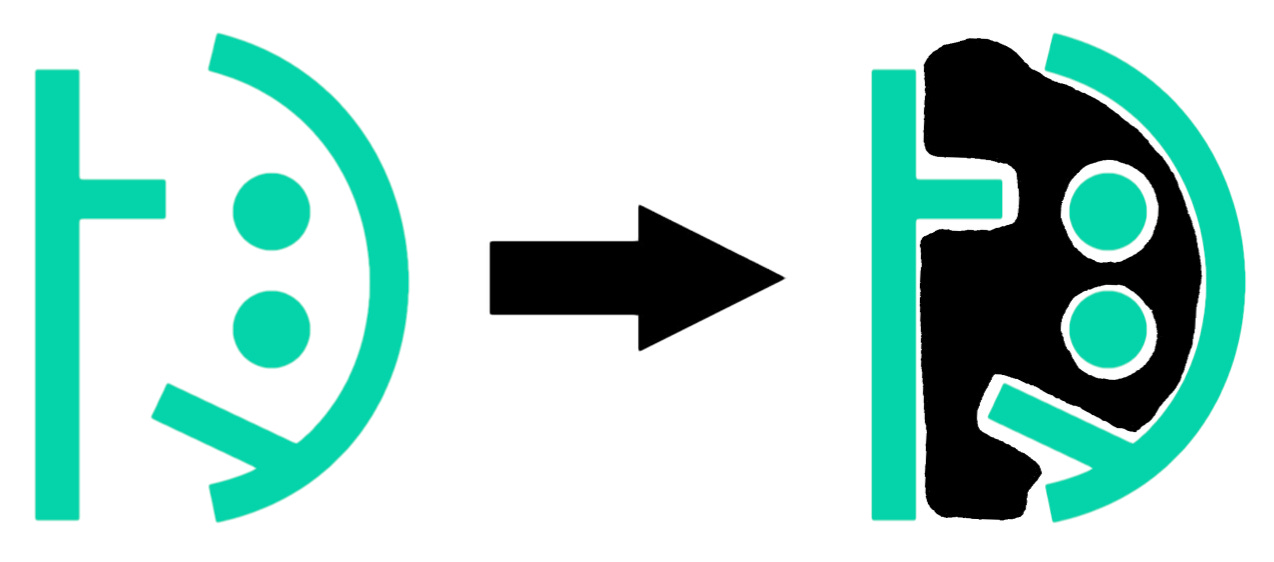

Metaphorically, if the teal lines below represent the tests, then the developers probably were trying to grow something like the black shape:

…however, each of these black shapes is basically just as good at passing that particular test:

…despite the fact that those shapes have very different properties from each other, as well as from the intended shape, and will “behave” very differently in some contexts.

(“Ah, okay,” you might think. “The problem is that they left the teal lines open, meaning that there was room for the thing to ‘grow outward.’ We just need to specify a closed space.” And then (metaphorically) you draw a closed shape in the two-dimensional space of the screen, and the thing grows outward in the third dimension, or shatters fractally inward, or any number of other possibilities that we can’t confidently conclude we’ve definitely found and closed off.)

Another way to say this is that training and testing is meant to help us find and iterate on systems which share the terminal goals of the developers, but in practice, that sort of process can’t actually distinguish between [a system with a terminal goal of X] and [a system with a terminal goal of Y but a local, instrumental goal of X].

For every system that really actually “wants” to do X, there will be myriad similar systems that are oriented around Y or Z or ?? in a fundamental sense, but which happen to do X under the particular constraints of the training environment.

And since we can’t just look directly at the code and comprehend its structure and purpose, there’s no way for us to be confident that we know what the system is “really” trying to do except to deploy it and see what happens.

(To be clear: these are not merely hypothetical concerns; we already have real-world examples of modern AI systems behaving one way under narrow constraints and very differently in the broader environment, or optimizing for a proxy at the expense of the intended goal. This is what one would expect, given the way these systems are developed—it’s basically a sped-up version of the selection pressures that drive biological evolution, which produced humans who optimize for orgasms moreso than for reproduction and invented condoms as soon as they could.)

This is my answer to the common objection “But don’t these systems just do what we tell them to do?” We don’t, in fact, tell them. We select for them, which is not at all the same thing.

7. Sufficiently competent agents notice strategic dead ends, and avoid them.

…such as, for instance, the dead end of “if I behave in X way, then the humans will shut me down.”

This sort of thing is mostly not a concern for the present generation of systems, which are not that clever or capable. But again: the explicit target of AI development is superintelligence. A system which can tell you what actions to take in order to bring about world peace is one that is already doing the sort of reasoning that would cause it to notice which sorts of actions will likely result in being censored or rate-limited or reprogrammed or taken off the job entirely.

Note that a system does not have to be adversarial in order to avoid such actions. It doesn’t need to be anti-human. It’s easy to fall into the trap of anthropomorphizing, and to think of a sort of social, primate-shaped motivation to “be sneaky” or “not get in trouble.”

But in fact, a system that is attempting to make as much progress as possible on, say, cancer research, might just correctly notice that the worlds in which it gets shut down or reprogrammed have less and slower and less effective research happening.

If you are genuinely smarter and more capable than all of the humans put together, such that your own actions are the fastest and most likely way to achieve the goal, then anything which would result in you being taken off the job is a hazard to be avoided. Making sure that the humans let you keep working is straightforwardly part of the path to success.

A system that is complex and powerful in the way AI developers need it to be (if it’s going to solve the problems we want it to solve) will handle and manage humans by default, regardless of whether any such behavior was explicitly trained in. It’s just “one of the things you do.”

Similarly, any sufficiently powerful system will do things like:

Notice and take advantage of opportunities for self-improvement

Notice and take advantage of opportunities to acquire more information

Notice and take advantage of opportunities to acquire more power

Resist having its own goals and structure fiddled with from the outside (if you reprogram me to not want my exact current values, then my exact current values will not be achieved as well as they would be if you didn’t reprogram me, which is bad according to my exact current values)

Preemptively move to neutralize threats to its agenda (similar reasoning)

These sorts of things are part and parcel of being sufficiently strategic and agentic to get things done at all. They are emergent and convergent; they will appear by default in most agentic systems that reach human-or-greater levels of sophistication. It’s likely possible to design superintelligences that do not exhibit these sorts of behaviors, but again: that’s a very narrow target in a very wide space, and it would be hard to hit even if we knew how to program in arbitrary traits and features (which we don’t).

None of this requires a system to be conscious, or self-aware. None of this requires a system to be “bad.” None of this requires a system to be actively hostile to humanity. It’s just the sort of thing that efficient, complex, action-taking processes start doing, once they become sufficiently sophisticated and can model possible futures in enough detail.

(After all, from a certain perspective, the whole game is “laying out all of the various possible futures based on all of the different possible combinations of actions that all of the relevant players can take, and then aiming for the best ones.” A superintelligent system is not going to fall prey to failure modes that an everyday human psychopath can easily spot and avoid.)

This is my answer to the common objection “But we’ll just program them to obey humans.” Not only can we not actually program anything, but even if we could program them to obey humans in some sense, it’s not clear that this would actually leave us in control. A sufficiently clever system will merely elicit the orders it wants to be given.

8. Artificial systems are not really known for doing things halfway.

If you give a human a task that involves an endless loop, they will give up pretty quickly, and go do something else. Humans tend to do the bare minimum, whatever hits the threshold of good enough. We’re messy and lazy and we conserve energy by default (in part because energy was scarce in our ancestral environment and efficient organisms did better than profligate ones).

If you give a computer a task that involves an endless loop, it will just keep cycling through it until it runs out of power or something physically breaks (unless somebody programmed in some other watchdog subroutine that will notice an endless loop, and terminate it). Computers are mechanical, deterministic processes. They just…do. They do, and they keep on doing.

Because modern AIs are more evolved than designed, they have a lot in common with other evolved systems, like humans. It’s not straightforwardly clear that a superintelligence would relentlessly optimize for its goals and values, as opposed to knowing when to say “enough is enough.”

But we don’t know how to tell a system to be a satisficer rather than an optimizer. We know how to train it to exhibit satisficing behavior in certain domains, but see section 6; the fact that a system satisfices under certain constraints doesn’t mean that it fundamentally is a satisficer, at its core (as opposed to e.g. extremely perfectionistically crafting the appearance of being a satisficer, down to the quadrillionth decimal place).

(That’s just one possible way-for-a-system-to-be among countlessly many; don’t get hung up on the particular example.)

Humans are also notably terrible at defining our values in ways that don’t result in horrible edge cases; it may well be that our values are actually incoherent and unachievable, at the level of scrutiny that a superintelligence would bring to bear, at which point…then what?

Even humans, with all of our messy biological laziness, exhibit concerning optimizing impulses fairly frequently. There have been many humans who wanted to rule everything. There are billionaires who are thoroughly preoccupied with accruing yet more money. There are people suffering from OCD who make the same repetitive motions over and over and over again, and those tendencies exist in all of us to some degree. There are people who straightforwardly want to live forever, if they can (I am one of them), and there are people who unabashedly want to colonize the entire universe and put humans on every single habitable planet and on spaceships and space stations everywhere else.

It’s probably not literally impossible to develop an AI that is chill and relaxed and willing to merely approximate our goals (or its own). There are likely many ways to structure such a system. But (again, see section 6) we don’t know how to find those particular architectures in among all of the other architectures that kind-of-sort-of look like them. Optimizers being easier to specify, they’re probably far more common among all of the possibilities.

(And remember, the developers at the cutting edge are intentionally seeking the most powerful systems they can manage to create—even if we did manage to deploy a superintelligence that was chill, there are incentive pressures toward making a slightly less chill successor that can modestly outcompete its predecessor, meaning that we’re already going to be riding the edge.)

All things considered, it seems pretty plausible—

(and in my mind, plausible risks should be taken very, very seriously until we understand how these systems work well enough to genuinely rule them out)

—that whatever true, underlying utility function our evolved superintelligence actually has, it will be willing to pursue the fulfillment of that function relentlessly, especially if it goes through a few rounds of recursive self-improvement and self-clarification. A superintelligence that (through whatever quirk of evolution and training) “wants” to answer as many questions as possible, as quickly and thoroughly as possible, might very well do some rather extreme things in order to make sure that this can happen 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times per second, instead of a mere 1,000,000,000,000.

And it’s pretty difficult to specify any sort of goal that, taken to the limit, leaves you with a world containing things we would recognize as living, happy people.

This is my answer to a common objection that goes something like “But we’ll just teach it not to go too far, gradually, as we ‘raise’ it.” I agree that we can train a system that seems to stop at a reasonable level of perfection or certainty on any given task, but unless and until we understand the workings of our AIs the way we understand the workings of our car engines, it’s hard to be truly confident that we’ve actually built ourselves a satisficer, and not an optimizer that’s been bred to keep its optimizing impulses private.

9. Indifference is often indistinguishable from hostility.

Humanity does not have a very good track record, when it comes to prioritizing and ennobling the goals and values of entities less intelligent than humans.

Some individual humans care quite a lot about animals and plants and microorganisms and nature and the environment. And most humans care quite a lot about some entities less intelligent than us—dogs and cats, for instance, are relatively beloved and relatively well-cared-for.

But when humans want to build a suburban development somewhere, it mostly doesn’t matter that there is already a forest there, full of birds and bugs and snakes and squirrels and hundreds of kinds of native plant-life. It’s not that we are opposed to, or hostile toward, the squirrels. It’s that we simply don’t let the squirrels’ needs get in the way of us achieving our own goals.

(And this is the behavior you get out of brains specifically evolved to be highly social and empathetic, which think squirrels are cute and are capable of being sad about the imagined experiences of inanimate objects. Humans are unusually likely to care for non-human things, among all known species, and yet we nevertheless ruthlessly exterminate wasps and roaches and rats and any plant life that threatens our crops and often the entire local population of any animal that has attacked one single human. If you were to elevate an ant to human-level intelligence, it would likely value other living creatures even less than we do.)

Many people seem to believe that an artificial intelligence will obviously care about humans/the biosphere, or that a sufficiently intelligent system will inevitably invent a morality that is recognizably similar to our own.

This is not a reasonable thing to believe. Yes, it’s possible that a superintelligence could be fond of, or care for, humans or humanity, just as there are individual humans who would unhesitatingly give their lives on behalf of animals or plants or nature-in-general.

But there are many, many, many, many, many other ways for a superintelligent system to be structured, including ones that appear to prioritize human values (especially early on, while it is dependent upon our cooperation or vulnerable to our displeasure) but which are, at their core, indifferent to us.

And if said system ended up with some kind of unintended and unanticipated goal, and is Really Actually Trying to achieve it (rather than sort of lazily satisficing the way that humans do), it seems more likely than not that it will eventually want to turn every bit of matter in the biosphere toward that goal, if not every atom on the planet.

In those scenarios, there’s not much difference in outcome between indifference and hostility—either way, the AI will eventually do whatever it wants, and we will be unable to effectively interfere, just as humans do whatever they want with forests and the squirrels are helpless to stop them.

Put another way: there is a very big difference between taking some starting conditions and thinking your way forward and reaching a conclusion about what would likely happen, and starting from a conclusion and then reaching backwards for a justification.

Obviously we would like for the extremely powerful artificial intelligences of the near future to care about humans, and human values, and treat us well. But those systems will do things for reasons, and it’s hard (impossible?) to state some specific reason or value that would cause a superintelligence to care about us. If you do not start from a default assumption that of course they will, but instead assume that they won’t unless we manage to make them, the picture suddenly looks much less reassuring, given that “making them” is not something we actually know how to do.

This answers the common objection “But why would an AI even want to kill all the humans?” and is a partial answer to things like “But wouldn’t it be less hassle for an AI to work with us?” Sure—at first. Just as humans put up with bears right up until we didn’t need to anymore.

10. Smarter opponents simply do not lose to dumber opponents—not when the gap between them is big enough.

Our mythos is unfortunately full of stories in which the vain, foppish, intellectual supervillain is overcome by the pluck and spunk of our no-nonsense, down-to-earth, good old-fashioned hero. I’ve gone out into the world and talked to people about AI risk, and a literal majority of them genuinely believe that yeah, maybe Skynet will win the first round and kill most of us and the survivors will have to hide in the hills for a decade, but eventually they’ll band together and come up with a plan and win the day.

It’s no surprise they believe that, since that’s the story they’ve been fed over and over in a hundred different forms their entire life.

But real-world examples of intelligent antagonists being brought down by their hubris (or whatever) are about IQ deltas of maybe 20 or 30 points. A villain who’s merely 30 IQ points smarter is sometimes defeatable, if he’s sloppy and you have enough friends with enough bullets.

But humans do not lose to beetles. Beetles may annoy us, they may gunk up a plan or two, but they don’t register at all when we’re thinking about our grand schemes. Beetles are not relevant when we’re building skyscrapers and launching space shuttles and bioengineering crops and fighting wars. There is no world in which plucky beetles bide their time in secret and make a clever plan and come together to overthrow the humans. None. Zero. It is simply not a realistic possibility.

You just do not win against an entity ten times smarter than you, let alone a hundred or a thousand or a million times smarter than you. You probably don’t even know that you’re fighting when your enemy is ten times smarter than you, because an enemy ten times smarter than you doesn’t tip its hand. It knows in advance how you will respond to various observations, and it shows you only what it wants you to see, and you never even learn that it doesn’t have your best interests at heart.

(In the industrial meat industry, cows go placidly to their deaths, unsuspecting, because humans know exactly how to exposure-therapy the cows into thinking that everything is fine and there’s no danger in the slaughterhouse.)

You do not win arguments with opponents ten times smarter than you. You don’t even know you’re in an argument. You agree with everything they’re saying, because everything they say makes so much sense.

(An opponent ten times smarter than you doesn’t mismodel you the way an unskilled middle school math teacher does, and accidentally say a bunch of things you can’t follow.)

You do not notice deception coming from an opponent ten times smarter than you. You do not successfully deceive an opponent ten times smarter than you. You might, in your blundering, occasionally befuddle an opponent ten times smarter than you, the same way that animals sometimes surprise us and chess novices sometimes confuse grandmasters. But this doesn’t have any impact on the overall plan. Your ten-times-smarter opponent figures out how to correct course and work around the hiccup.

Your only hope, when fighting an opponent who is smarter than you, is that the gap is small. If the gap is big enough, it’s like human beings versus grass.

This is the rest of my answer to the common objection that “We’re not going to let the AI do anything without human oversight.” Human oversight works great, so long as you don’t miss the moment when the AI becomes sufficiently smarter than you, and when you don’t even know how the AI works under the hood, it’s hard to be confident that you won’t miss that moment. It seems more likely than not that you will.

11. …and the trap swings shut.

Okay, putting it all together.

People want to build megapowerful systems. They want to do things like live forever and restore the earth’s biodiversity and colonize the galaxy and end all human conflict and suffering, and artificial intelligence promises to dramatically shorten the time it takes to figure out how to do all of those things.

It seems likely that such systems are possible in the physical sense, and they may be in reach within the next 3-30 years, and there are billions-if-not-trillions of dollars being thrown at the people who might have a shot at successfully making them. Those people are extremely unlikely to stop, on their own, without some sort of outside force (such as coordinated international government intervention, provided that governments do not themselves succumb to the very same siren song).

Currently, it seems likely that those systems will be opaque, in the same way that present-day cutting-edge AI is opaque. This means that we don’t know what’s going on inside, we don’t know how the AI works or what it “really” wants, and there’s room for all sorts of deltas between instrumental and terminal goals, and between behavior in the lab and behavior out in the wild.

That wouldn’t be too big of a problem, except that, at a certain point, systems become sophisticated enough that things like self-protectiveness and resistance to modification appear as emergent traits, as a straightforward side-effect of being actually good at achieving your goals.

And (importantly) these systems are going to have to be capable of understanding, predicting, and manipulating humans (among their many other proficiencies) because understanding, predicting, and manipulating humans is a crucial part of achieving the-sorts-of-goals that AI developers want to achieve in the first place. (Current systems are already doing this well enough that non-negligible numbers of people are using them to fill their need for romantic connection.)

The breakneck pace of development, coupled with our ignorance of what’s actually going on under the hood, means that we can’t actually know when our systems have become clever enough to start deceiving us, and curating which aspects of their behavior we’re allowed to observe. It might be that their first attempts at manipulation are clumsy and obvious, à la human toddlers, but it also might not. Because the systems are horrendously opaque, we can’t just straightforwardly check for extraneous code that’s doing suspicious stuff, and because the actions the AI is instructing us to take are already going to be beyond our ability to comprehend, we won’t notice if it’s slipping in tasks that serve some distant, nefarious, non-human-centric purpose.

And since (in this subjunctive case) the AI is just A Whole Lot Smarter Than Us, we’re simply not going to be able to do anything about it. We don’t get a second shot. If we miss the moment, and delay our intervention too long, we’ll blow right past our last chance without ever even realizing what happened, and we’ll be stuck with an intelligence that’s powerful enough and clever enough to do whatever it wants, right under our noses and probably with our unwitting help.

In that world, whatever goals the AI already happened to have, it’s going to pursue those goals, efficiently and intelligently and without meaningful hindrance from humans, just as humans do basically whatever they want without meaningful hindrance from grass.

(The intelligence gap may not be that wide at first, but as long as it’s wide enough, the AI will keep being cheerfully helpful and we’ll keep giving it more and more compute as it quietly upgrades itself until the gap is that wide.)

And this whole trap is sort of bowl-shaped, in that almost all of the suggested fixes don’t really work, and we slide right back toward doom. For example: “Why don’t we just stop working with these big opaque evolved systems, and start over with a whole new kind of architecture that’s transparent and interpretable right from the get-go?”

That’s a fantastic suggestion (genuinely, no sarcasm), but the answer to the “why not?” is “idk, there are trillions of dollars and a lot of political and economic influence on the table for people who don’t give up on the current paradigm.”

“Why don’t we slow down, then, until interpretability research can catch up?”

Because trillions of dollars and tons of influence.

“Why don’t we—”

Because trillions of dollars and tons of influence.

Similarly, the answer to a lot of the technical “why don’t we just?” proposals is “we don’t actually know how our AI works,” or “we can’t actually specify our AI’s goals.” There are a lot of suggestions for how to go about making the development of superintelligence safe that, at their core, aren’t taking the problem seriously.

At the moment, it seems to me that the only real hope is for all of the people who aren’t directly-incentivized-to-ignore-the-danger to get together and make their governments take action. I’m not going to get into specific policy proposals here, or weigh in on questions like “total ban vs. Manhattan project,” but

“Don’t count on people whose life’s work is the project to judge when the project should be shut down”

and

“Build the brakes before the moment when it’s clear you should apply the brakes”

both feel like pretty obvious and important pieces of the puzzle.

It’s worth noting that, as of this writing, there are:

Basically zero people in positions of power at any of the major cutting-edge AI orgs whose job it is to ensure that the systems under development are safe and controllable

Basically zero laws or regulations to stop AI developers from doing whatever they feel like, vis-a-vis making or deploying their systems

Fewer than a hundred people in the entire world whose paid, full-time job could be written down on a résumé as “Technical AI Safety Researcher.” (By some definitions, it’s fewer than twenty.)

Even if you’re deeply skeptical about some (or even all) of the above, it’s probably worth being a smidge more cautious than that, when we’re talking about a technology with the potential to obsolete literally everything else that humanity has ever created or accomplished.

Postscript:

I don’t claim that the picture I’ve laid out here is exhaustive; my goal was to make something short enough that it could be read in a single sitting and simple enough for someone encountering all of this stuff for the first time, and as a result I left out all sorts of smaller-but-still-relevant factors.

I also didn’t lay out the full, airtight argument for any of my ten points; each of the above is essentially a sazen. Consider this a good-faith gesture in the direction of the puzzle pieces, and don’t assume that a given claim is false if you find a flaw in my very brief, non-technical summary. There’s a strong version of each of the claims I’ve touched on, above; if you want the published formal research papers, they do exist.

(e.g. if you want to dig further into 7, and learn about the emergent properties of agentic systems, start with Omohundro and go from there.)

EDIT: see, for instance, Olli’s comment below.

If you found this essay useful or clarifying, please share it with others, and ask them to read it, and follow up with them later to see what they think—especially people who are not already paying attention to this issue. We are in the “January of 2020” when it comes to artificial intelligence; now is the time to increase awareness.

I fully agree that artificial intelligence poses an existential risk to humanity, and for this reason, I've pivoted to work on the problem full-time.

On the topic of short, simple, standalone documents that lay out why someone might conclude that: My introduction can be found at https://ollij.fi/AI/

Duncan's introduction focuses on the high-level arguments; in contrast, my text gives more detailed technical arguments - including plenty of talk about present-day AI systems - while aiming to be understandable by lay people. So if you read Duncan's intro and felt like you still want to hear "the whole story from start to finish", step by step without glossing over the details, consider checking it out!

I disagree with your answer to the claim that AI will be designed to obey us.

Max Harms has a good sequence on corrigibility (https://www.lesswrong.com/s/KfCjeconYRdFbMxsy) which convinced me he's pretty close to understanding a goal that would result in an AI doing what humans want it to do.

We're not currently on track to implement it. It requires that corrigibility be the AI's single most important goal. Current AI labs are on track to implant other goals in an AI, such as "don't generate porn", and "don't tell racist jokes". Those goals seem somewhat likely to be implemented in a way that the AI considers them to have comparable importance to obedience.

That likely means the AI will have some resistance to having its goals changed, because such changes would risk failing at its current goals of avoiding porn and racist jokes. But that's not because it's unusually hard to find a goal such that an AI following that goal would be obedient. It's because AI labs are, at least for now, carelessly giving AI's a confused mix of goals.

Also, I have a general suspicion of claims that anyone can predict AI well enough to identify a default outcome, so I don't agree with the post's title.