Strategic Convergence Among Relatively Intelligent Antagonists

Or, What Would I Do If I Were Smarter?

Author’s note: I first conceived of the core of this essay in 2016. The dream was that at some point I would set aside six months to flesh it out with full diligent rigor and publish a formal academic paper. Alas, those six months never cohered. As I’m still quite confident in the core claim, though, I decided not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good, and to publish it here in its less-polished form. Consider this more of a spotlight in a promising direction than a complete and grounded theory.

“They can predict you better than you can predict yourself, so you think you’re being clever or unpredictable but you’re actually just patently transparent to them.”

0. Introduction

Claim: Relatively intelligent antagonists—

(i.e. those entities whose advantage lies primarily in superior intelligence, as opposed to greater physical strength or a larger base of resources or stronger social connections, etc.)

—tend to converge on a small number of similar strategies, regardless of the domain or the specific details of the conflict. These strategies emerge naturally from the fact that relatively intelligent antagonists are capable of taking a broader scope than their opponents, and are better equipped to model and manipulate those opponents, including via superior coordination and disrupting those opponents’ ability to coordinate with their allies.

Understanding the resulting strategic convergence is useful in that it provides one with:

A better sense of where to look, when one fears one might be up against a more intelligent antagonist, which in turn makes it more possible to mount an adequate defense (provided that the intelligence difference is not extreme)

A scaffold for increasing one’s own ability to access more sophisticated strategic space (i.e. successfully mimicking the choices a more intelligent agent would make in one’s place)

In plain speech:

There’s a trope of incredibly clever heroes and villains (Odysseus, Ozymandias, Sherlock Holmes) outwitting their opponents in delightfully convoluted and surprising ways, but in reality, smarter agents tend to win out over less intelligent ones using, basically, the same couple of tricks every time. There are variations on the theme, but there’s pretty much just one theme—there’s one core Thing that being smarter than your opponent lets you do.

(In fact, Odysseus and Ozymandias and Sherlock Holmes do this one Thing, too.)

This essay is about understanding that Thing. It’s about the core strategy that most-if-not-all relatively intelligent antagonists converge upon.

I. Triangulating Antagonism

The word antagonism is large and vague, and has connotations of strong emotional motivation (à la malice or animosity) that are not necessarily intended here. Rather than attempting to give a complete and concise definition of what is meant by the term antagonists, I will instead refer throughout the piece to the following eight example conflicts:

Parents vs. their toddlers

Humans vs. their livestock

Pack hunters (hyenas, dolphins, wolves) vs. their prey

Psychopaths/conmen vs. the credulous people around them

The British WWII-era “Ultra” cryptanalysis group vs. the Nazis

A chess master vs. their protégé

Individuals planning a surprise party vs. the party’s recipient

An artificial intelligence vs. the human decisionmakers attempting to align and restrain it

From the above, it should be clear that antagonists are agents with some degree of control over their environment and their actions within it, and with goals that are mutually incompatible in at least some ways (i.e. at least partially zero-sum). They need not necessarily be enemies in the traditional sense, but competitors willing to secure success at their opponents’ expense—for instance, one doesn’t traditionally think of surprise party planners as being in an antagonistic relationship with their target, but to the extent that their target is naturally curious and threatening to unravel the ruse, they are in direct conflict with the overall goal of preserving the surprise.

Here, by the way, is an excellent place to pause if you’d like to do your own thinking on the puzzle that I’ve laid out, before I share more of my own thoughts. The claim of this piece is that there is a common analogy between all of the above pairs, and that, in each of the above conflicts, the first named agents employ roughly the same broad strategy against the second named. You may want to form some unanchored thoughts on those claims before reading further, or note questions or nascent objections to see whether they are answered later or not.

II. Defining Intelligence

Nick Bostrom has defined intelligence as “something like instrumental rationality—skill at prediction, planning, and means-ends reasoning in general” (Bostrom 2012). For the purpose of comparing intelligences, this definition may be clarified by further breakdown into three broad competencies:

Sensory competence, or the degree to which an agent is capable of extracting information from its environment. Sensory competence is not limited to direct physiological input such as vision or hearing; it may also include the ability to access remote information (e.g. that which is stored in documents, databases, or the memories of other agents). All else being equal, an agent that is robustly capable of acquiring more information about its environment than its opponent can be considered more intelligent in the sense intended here.

Analytic competence, or the degree to which an agent can draw relevant meaning out of the information available to it. Analytic competence may be contextual (imagine two otherwise equally capable agents, one who speaks only Russian and one who speaks only French, each presented with the same French document) or general (imagine two agents with substantially different rankings on an IQ scale, each performing the same algorithmic analysis on a set of cryptographic data). It may vary based on factors such as mental state, processing speed, or access to computational tools. All else being equal, an agent that is robustly capable of deeper analysis, or of accomplishing the same analysis in less time, should be considered more intelligent than its opponent.

Generative competence, or the degree to which an agent is capable of extrapolating from the analysis it performs—conceiving of multiple plausible hypotheses or models, outlining various possible courses of action under those models, and simulating a range of consequences likely to result from those actions, prior to committing to any particular strategy. Generative competence may range from the ability to execute a simple “random walk” (e.g. the process of genetic mutation may be said to possess sufficient generative competence to drive evolution over long time scales) to the ability to create targeted and complex plans complete with branches and contingencies. Like analytic competence, it may be bolstered or hindered by factors which may be more or less durable.1

In short: what can you see, what can you understand, and what can you do with that understanding?

Together, these three competencies determine an agent’s effective access to information—how much of the universe it can detect, comprehend, and predict or influence, which is a plausible operationalization of what is usually meant by the word intelligence. All else being equal, a substantial advantage in any of the three competencies would qualify an agent as “more intelligent” than its opponents2.

In the above eight example conflicts, there are certainly other factors in the mix—parents have a great deal more physical strength than toddlers, for instance, and humans bring a large number of tools to bear in their attempts to corral and control their livestock.

But in each of the eight, intelligence plays a major role, and in some it is compensating for notable disadvantages.

Here is another good place to pause, if you want to surface any confusions or objections with the above rough model. If something crucial were missing, what would it be? What if intelligence were better modeled by a division into four competencies, or two, or five? (Or three, but a different three?) Is there a way for one agent to possess superior sensory, analytic, and generative competence than another agent, and yet not be effectively more intelligent than that second agent?

III. Black Boxes

Later sections in this essay will speak to the importance of both scope and coordination in intelligence-based conflicts. However, both of those rest on what seems (to me) to be the central foundation of the smarter agents’ strategic dominance: modeling.

In short: relatively intelligent antagonists do a better job than their less-intelligent opponents at understanding which sensory inputs will lead to which behavioral outputs, and they use that superior understanding to manipulate those behavioral outputs, feeding their opponent whatever sensory data is required to elicit the desired reactions. They don’t (often) try to change their opponents’ algorithms, but rather take advantage of and use those preexisting defaults.

Parents distract their toddlers at key moments with brightly colored objects or surprising sounds, and hide items that they don’t want the toddlers to notice, and employ tactics like spelling out words that the toddlers would otherwise recognize so as to route around the toddlers’ understanding.

Herders and farmers carefully desensitize animals to the slaughterhouse environment so that they will be calm and unpanicked when the actual day of slaughter arrives. They do things like arrange for cows to get their legs stuck in a grate, and then later paint lines on the ground that resemble a grate to a degree sufficient to deter the cow from approaching.

Pack hunting animals will often have one or two highly visible members that frighten their prey and send them toward apparently safe territory that actually contains more hunters lying in wait.

Psychopaths and conmen present as charming, or confident, or bumbling and in-need-of-help, or whatever other apparent trait will elicit the desired reaction from their mark, and lay the groundwork for the next move of the game.

The Ultra team allowed multiple known future Nazi attacks to go through, sacrificing ships and soldiers rather than tipping their hand and revealing that the Enigma code had been broken. They carefully ensured that the Nazis would never observe conclusive evidence of Allied foreknowledge, and for many months only acted in ways that had other plausible explanations.

A chess master will often create an apparent vulnerability, luring a less-skilled player with expendable pieces, causing that player to overextend in ways that can be taken advantage of many turns later (beyond the less-skilled player’s time horizon).

Individuals planning a surprise party almost always deploy some sort of plausible ruse—an excuse to cause the subject of the party to be where they need to be, at the relevant time, without arousing major suspicion.

An artificial intelligence which is aimed at some unexpected, ulterior goal would likely hide some of its movements while presenting plausible justifications for those movements it could not successfully hide.

In these and other analogous cases, the relatively more intelligent agent relies on its ability to curate the experience of its less intelligent opponent, feeding it carefully selected inputs to shape and direct its subsequent beliefs and behavior. And this curation has its foundation in the intelligent agent’s ability to model its opponent—if you don’t know which inputs lead to which outputs, then you can’t curate and manipulate (or, more specifically, your ability to curate and manipulate is proportional to your understanding of which inputs lead to which outputs).

And it’s the ability to observe and analyze your opponent’s behavior that allows you to create a map of their if-thens in the first place, and to use that map to generate pathways to victory.

IV. Scope

Before diving into scope, I want to note that the previous section was fairly short, and went by somewhat quickly, and thus may not have hit hard enough or carried weight commensurate with its importance.

The smarter agent does a better job of modeling its opponent as a machine whose various buttons may be pressed, to cause various behaviors. The less intelligent agent may not be engaged in such a process at all, if it’s unaware that it is in the presence of an antagonist, and will do so less well in any case, due to a deficit in at least one of sensory, analytic, or generative competence.

(Deficit in sensory competence: takes in less information about its opponent in the first place; sees less of what its opponent is doing.

Deficit in analytic competence: is less able to convert its observations into clear models; can’t tease out the if-thens from the pile of observations.

Deficit in generative competence: may understand the if-thens, but is less capable of turning that understanding into an actionable plan; can’t see what sequence of manipulations to make in order to achieve the desired ends.)

This is the core claim of the essay. If you were to stop reading here, you would have more than half of the value I’m hoping to convey. What’s left is a closer look at some substrategies that emerge from this central principle, and I think that exploration is valuable, but even though I’m going to spill as-many-or-more words on those substrategies, the insights therein are not as key as the above. These paragraphs are here mostly to … lend appropriate weight? … to the previous section. To underscore it, and let your mind digest it a little bit further before rushing on to the next thought.

(You could even stop here for the night, and come back and finish the rest of the essay tomorrow, if you wanted. I think this is not a good idea if it causes you to never read the rest, but it’s probably better than reading it all at once if you actually anticipate returning later.)

One of the key ways in which relatively intelligent antagonists convert their superior capacity into tangible advantage is by using that capacity to take in a broader scope than their opponent.

By “broader scope,” I mean at least two distinct things:

Greater horizons within the same game (e.g. a chess opponent who can think seven moves ahead rather than only three)

Playing a different and larger game (e.g. a chess opponent whose true goal is not to win at chess but rather to manipulate the audience’s perceptions of each of the chess players, for some other goal that may be romantic or political or professional, etc.)

…both of which seem to me like expressions of the same underlying pattern (and so I may not clearly distinguish them in later examples).

Parents are capable of executing more complex plans, incorporating a wider variety of factors and a substantially larger time horizon, than their toddlers. Farmers and hunters weave nets (both literal and metaphorical) that are often beyond the animals’ ability to comprehend—in many cases, by the time their targets even perceive the boundaries of a given trap, it’s already too late. Victims of conmen and psychopaths often think that they are straightforwardly helping a stranger, or caring for a friend, or taking advantage of inside information, when in fact that whole dynamic is merely a subsection of a larger and more complicated process.

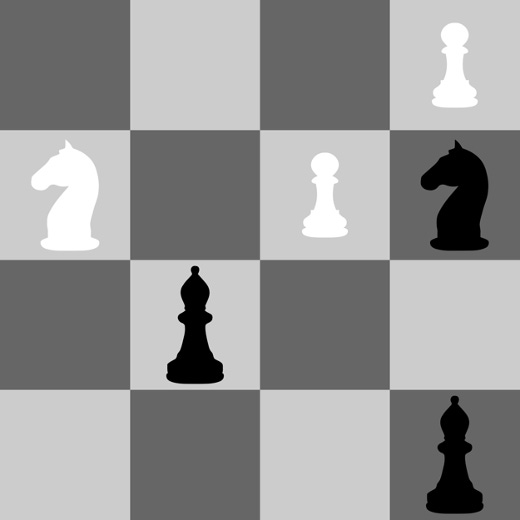

To return to the chess metaphor:

In figure 1, a white pawn has moved into position to threaten the black bishop. If one naïvely assumes that there are no other relevant details, the correct response is for the bishop to move up and to the right, taking the pawn.

And indeed, there are chess players for whom [four squares and one turn] is genuinely the most that they can process, and who would straightforwardly fall for this trap, their attention caught and focused by the movement of the white pawn the same way a cat’s attention can be caught by a wiggling string.

(Imagine, for instance, a typical four-year-old, learning chess for the first time. And in larger, more complex real-world conflicts, there are indeed analogues to the four-year-old chess player, such as individuals who have strong emotional triggers around particular topics, and can be tunnel-visioned as a result.)

There are more than four squares on a chessboard, though, and if the black player is capable of taking a broader scope, they may well benefit from doing so. When one includes the twelve surrounding squares (as in figure 2), it becomes clear that the bishop, upon taking the pawn, would be taken in turn, and a much more attractive option is to take the white knight by moving up and to the left.

(Figure 2 also shows that the pawn now threatening the black bishop was previously in a position to take the black knight instead, which invites speculation as to why the white player forewent that opportunity.)

If we broaden the scope further still (as in figure 3), it becomes clear that the situation is yet more complex and nuanced, with multiple protective relationships between pieces and a cascading set of more-or-less-likely consequences from black’s next move. The kings have become visible, changing the apparent goal from “make net-beneficial trades” to “productively move toward checkmate,” and now the black player must take into account not only the threat to its bishop (i.e. the white player’s next move), but also how it will respond to that response given the current arrangement of strength, and how that response will be responded to in turn.

All of this is a metaphor, but the metaphor is sound/tight. Reality is a chessboard with billions of squares, millions of relevant pieces, and many, many subgames—in such an environment, an agent’s ability to make optimal moves is directly tied to its ability to incorporate ever-greater swaths of territory into its calculations (or, conversely, to correctly identify certain swaths as strategically irrelevant, rather than wasting resources on them).

As more and more of the surrounding context is taken into consideration, the interaction between black and white ceases to be strictly logical and deterministic and instead becomes probabilistic—there is a shift from a paradigm in which black has one clear “right move” toward one in which many different moves may be more or less likely to result in progress toward the goal.

And of course, the complexity of the board state is not the only relevant factor. As the constraints of obviousness loosen, the fidelity of the black’s model of white becomes equally crucial—does the black player understand the white player’s thought processes? Does it know how far out white is tracking, and what elements of the game are beyond white’s ability to properly attend to? Does it know which pieces white is willing to sacrifice versus which it is determined to protect? Can it tell the difference between white’s subtle tactics and misdirects versus white’s actual mistakes, and can it capitalize that knowledge?

When complexity is low, intelligence differentials may not matter, since both agents may be sufficiently competent to track all of the relevant detail—there are plenty of eight-year-olds who can reliably force draws in tic-tac-toe even against adult geniuses. But as complexity stacks up:

The agent with greater sensory competence may gain a meaningful advantage through its ability to distinguish subtle differences between similar inputs and outputs, and thereby tease out relevant causal factors that might otherwise be left out of a model. For instance, a superior observer in a game of chess can glean information not only from the movements of the pieces, but from the time elapsed between movements, the focus of the other player’s attention, small subvocal communications such as sighs, mutters, facial expressions, etc.

The agent with greater analytic competence may gain a meaningful advantage through its ability to keep track of a larger number of variables (and therefore to include more factors of low-but-nonzero import in its analysis, where its opponent must simplify and prioritize), and to more accurately approximate the ways in which those variables interact.

The agent with greater generative competence may gain a meaningful advantage through its ability to posit a larger number of testable hypotheses about the nature of its opponent’s algorithm, and to more thoroughly search through the space of possible strategies given its eventual model. In both cases, the more generative agent is less likely than its opponent to fail to consider true explanations and successful strategies in the first place.

V. Scope, Broadened

What follows is an abbreviated, non-comprehensive look at some of the ways in which one agent may take a broader scope than its opponent; for each of the following, the same sorts of advantages accrue to whoever can bring greater sensory, analytic, or generative competence to bear:

i. Physical space

Including more territory in one’s observations and calculations, which often allows for:

The recruitment of more physical or social resources

The ability to hide, maneuver, and choose the field of engagement

The ability to change one’s priorities/choose different victory conditions (as when the kings appeared, in the chess example)

ii. Time

Broadening one’s time horizons, which can reduce unnecessary and self-inflicted time pressure and open up a wider strategic space, including the possibility of planned setbacks/allowing one’s opponent the appearance of progress or success while you regroup and plan and amass resources. Goes hand in hand with:

iii. Modeling the self

Spending more computational resources on clarifying one’s own needs and values; replacing rough proxies with clearer expressions of the actual ends those proxies were approximating (e.g. determining which is more important: defeating one’s opponent, or having one’s opponent know that they were defeated, and by whom). Allows a more efficient expenditure of resources and a more careful prioritization of goals and targets.

iv. Modeling the opponent

Spending more resources building a richer and more nuanced model of the opponent, such that one can e.g. more finely predict what the opponent will find suspicious or plausible and how convincing various deceptions will be. Notably, a relatively intelligent antagonist will tend to be more capable of safely observing its opponent, and thus gathering more of the relevant data in the first place, which in turn allows for yet more observation, to gather yet more data (e.g. hunters observing deer from blinds without the deer being aware of the hunters).

Additionally, when two opponents are both seeking to find a playing field in which they have the advantage, the more intelligent one is more likely to be able to identify fields in which the less intelligent one believes that it has the advantage, and is wrong.

v. Expanding the boundaries of the conflict itself

Looking beyond the commonly-accepted set of resources and constraints, for other elements that can be brought to bear, e.g.:

Cheating—in games, players might shout “hey, look over there!” and then move pieces around, or smuggle in an extra ace, or tamper with code to secure hidden information or provide themselves with unexpected capabilities.

Recruitment—in disputes between colleagues or romantic partners, one or both of the involved party might preemptively move to disseminate their side of the story, and gather organizational or social support from peers or superiors. In general, relatively intelligent antagonists will be better positioned to coordinate, either with other intelligent allies or with subordinates/pawns.

Disruption—in similar fashion, relatively intelligent antagonists are better positioned to prevent coordination among their marks/targets, as with wolves cutting the weakest caribou from the herd, or spies fomenting mistrust and suspicion among their enemies.

Escalation—in conflicts where an agent perceives it will lose at a given level of violence or destructiveness, it might switch to more damaging and unexpected strategies (e.g. a victim of verbal bullying launching a physical attack).

vi. Changing the game entirely

As mentioned above; switching from a goal within the defined conflict to treating the defined conflict as a piece or move within a larger domain.

VI. What now?

One thing that I think needs to be made absolutely crystal clear:

Understanding the general strategy by which relatively intelligent antagonists win is not enough to overcome a large-enough delta, where “large enough” may well be as small as “twenty IQ points.” It is not the case that, should you be able to convey this insight to a cow, the cow will then successfully spy the farmer’s manipulations, and thwart them.

(Indeed, one version of this essay was going to frame the insight primarily as a warning about superintelligence, and how the superintelligence would outwit us even as we actively sought to spot its machinations.)

This is not a “how to win against things twice as smart as you” manual, because no such manual exists; you either already have enough bombs in the right places that their superior intelligence is not a problem, or you Just Lose.

That being said, there are a lot of situations where your relatively intelligent antagonist really is only slightly smarter than you, and executing their manipulations with a very slim margin, and in those cases, I think remembering this model can give you a very real edge.

(Psychopaths and conmen versus their victims/marks is one such conflict, at least a lot of the time.)

If you suspect malice from a mildly more perceptive, mildly more analytical, or mildly more generative enemy, then you should expect them to be doing, basically, one of two things:

Taking a broader scope than you

Trying to curate your experience so as to elicit convenient responses from you

Each of those hypotheses does narrow the space productively—it’s much easier to answer a question like “if my opponent were looking slightly farther afield than me, or playing a game that’s one step larger, where might the threat be?” than one like “how might a smarter person hurt me in this situation?” Pausing to consider what resources lie just outside of your default horizons, and then to go check whether those resources are being marshaled against you, is tractable, as is pausing to consider what the present gameboard might be a distraction from, or a mere element of.

Similarly, noting the ways in which you yourself are responding to stimuli (according to your normal, accustomed patterns) and asking yourself who or what might be benefiting from those responses, or who or what might be funneling you those prompt experiences, is a small-enough question that it’s worth setting a five-minute timer to try answering it, if you suspect foul play.

"This folly does not become you, Lucius," said the boy. "Twelve-year-old girls do not go around committing murders. You are a Slytherin and an intelligent one. You know this is a plot. Hermione Granger was placed on this gameboard by force, by whatever hand lies behind that plot. You were surely intended to act just as you are acting now—except that Draco Malfoy was meant to be dead, and you were meant to be beyond all reason. But he is alive and you are sane. Why are you cooperating with your intended role, in a plot meant to take the life of your son?"

The idea here is not to become an unpredictable agent-of-randomness, such that you can’t be modeled and thus can’t be steered, or to dig in your heels and do the opposite of what you think they want—

(Reversed stupidity is not intelligence, and multiplying your usual outputs by -1 only makes you slightly harder to puppet.)

—but rather to build into your decision-making algorithms some additional flexibility, à la split and commit. “If these events are natural occurrences, then I will respond according to my usual heuristics with Action X; however, if I have reason to believe that I might be being manipulated, I will instead do Action Y.”

(Sage advice, which might be heeded more often if it were actually given more often.)

And in the meantime, you can go looking for evidence that would distinguish the world where you want to X from the world where you want to Y, bolstered by little clues like “is this enemy of mine suddenly and inexplicably being nice?” or “does my opponent seem curiously unbothered by my sudden ascendancy in our back-and-forth?”

Alas, antagonists who are way smarter than you won’t leave such clues. But those who are ahead of you by bare margins often don’t have the spare resources to pick up every single breadcrumb, and as they say, forewarned is forearmed.

Good luck!

Such as an agent’s inherent sense of whether various lines of thinking or planning are allowed, given its values and context; “…high susceptibility by the individual to conformity pressures tends to be associated with certain personality traits that are detrimental to creative thinking” (Crutchfield 1962).

It should be noted that an effort to divide intelligence into these three competencies falls firmly into the category of “wrong, but useful.” That is, thinking in terms of sensory, analytic, and generative competence allows us to tease out various interesting detail in the clash between opposing intelligences, but in many ways all three competencies overlap and influence one another and share dependence on a common underlying mental architecture. As of this writing, I am aware of no research that supports any such division as a matter of objective reality, and other classification schemes may provide different (and possibly greater) insight.

How would you characterize the case of poker? As a reasonably experienced player, my worst game is against a complete novice, because they barely even know the rules and therefore act essentially randomly or at least unpredictably. Is this part of a class of edge cases where superior knowledge and intelligence doesn't help? Or does your theory predict that a sufficiently higher level of capability exists to handle even this case?

This seems like a good insight, but it seems like the word "antagonist" is pulling a lot of weight in your story. Like, I suspect that most of why superintelligence is dangerous routes thru other pathways than antagonism. For instance, intelligence yields more ability to acquire power/etc per unit time, independent of any interaction/deception/manipulation. Which doesn't invalidate your thesis, but seems worth keeping in mind when there's an intelligence difference between unaligned entities.