I.

Randall Munroe, author of the popular webcomic XKCD, once published this gem:

The comic has a safe, reasonable, motte interpretation that goes something like:

“People often underestimate the complexity of various problems or dynamics, and the degree to which existing equilibria are, in fact, pretty darn good, given constraints. Most of the times that people think they’ve spotted an easy, obvious better way, they’re wrong.”

I like that moral a lot. It’s in line with standard wisdom like Chesterton’s Fence, and not falling prey to fabricated options. It’s a good idea, when imagining oneself or one’s ideas to be possibly exceptional, to keep closely in touch with the fact that probably not.

Unfortunately, the comic also has an expansive, overconfident bailey interpretation, and it’s overwhelmingly how I see it used and cited in practice, and it lines up with a bunch of Munroe’s other takes, and so even though Munroe would almost certainly deny it, I’m pretty sure it’s secretly what the comic was actually trying to say:

“I thought there was a way to do this stuff better and smarter than everyone else, and it turned out I was wrong, and the reason I was wrong is because it simply cannot be done better; anyone who thinks so is going to end up with egg on their face just like me, in the end.”

This is a vibe I run into all the time, including among people who really ought to know better by now (e.g. aspiring rationalists). People post this comic (and sentiments like it) as mic drops, trump cards, argument stoppers.

II.

Mythbusters was a pretty decent show, and in a counting up frame they get a million points for caring about truth at all, which is a thing approximately 99.9% of popular entertainment does not even pretend to do.

But counting down, I give them a pretty large demerit for a substantial number of episodes that basically argue:

“We tried to achieve X, and were unable to; therefore X isn’t possible and never happened. Myth: BUSTED.”

III.

Earlier drafts of this essay toyed with naming this particular fallacy after Munroe or the Mythbusters, but in the end that seemed too harsh since they are far from the only people doing it. Instead, I’m calling this the magnanimous error, because it’s usually accompanied by a sort of smug, simpering, condescending forgiveness—oh, don’t worry, I made the same mistake myself in my own youthful idiocy, and I didn’t listen to people trying to warn me, either. You’ll see the light once you have a little more experience, and then we’ll laugh about our shared failures together.

The basic pattern looks something like this:

A person has a belief that boils down to some kind of personal exceptionalism. They think that they can do an X that everyone else has failed at, or they think they lack flaw Y that everyone is supposed to have, that sort of thing.

That person turns out to be wrong; reality corrects their misconception, often brutally. Their attempt at X backfires, or they suddenly gain perspective and realize that they’ve been doing Y all along and were just blind to it.

They react by updating to a belief that looks something like “it is not possible to be special in that way; anyone else who claims the specialness I used to claim is wrong in the same way that I was wrong about myself.”

I don’t claim to understand the gears of why people do this; I’m sure there are many various reasons and I’m sure that different people have different samplings from among those reasons.

But at least some of this effect sure does seem like it’s well-explained by a sort of egoic self-protectiveness:

[suffers a public, embarrassing setback]

It’s not that I, specifically, was wrong about me, specifically! No, no, no, it’s that the whole swath of possibility that I was banking on turned out to be illusory. Good thing it’s impossible, and not just a skill issue/a me-problem. 😅

For at least some people, it seems to be really really important that they be able to cling to the belief that nobody outstrips them on this axis; that everyone is more-or-less incapable of this particular feat, and terrible in this particular way.

IV.

Here are just a few specific examples that I’ve seen in the wild in the past year or so (this list could easily have contained twenty or thirty items):

“People kept telling me that I needed to get more in touch with my emotions and do more emotional processing. I kept telling them that my emotions just weren’t particularly strong and they didn’t have much of an influence on my behavior and decisions, and they kept insisting that I had a blind spot and was in denial. Now I’m embarrassed that it took me so long to realize they were right.”

“I used to claim that my facilitation was neutral, unbiased, objective, not imposing a worldview, etc. But believing that you can be inert and non-influencing in this way is evidence of a fundamental misunderstanding of how reality works.”

“Don’t even bother trying to get away from the monkey status games and social maneuvering. It won’t work. You can declare all you want that you’re doing something different, but you do not actually get to do that.”

“You can’t actually expect people to just…notice what’s bothering them, and bring it up, and calmly and reasonably talk it through. You can’t actually agree to not have conflict, or to only have gentle conflict, or promise to have good faith. When people agree to do that, they’re lying, or at best deceiving themselves, and it just drives the discomfort and the disagreement under the surface and it eventually comes out sideways.”

“Yeah, I used to say that my shadow wasn’t causing me any problems, either, until I realized that that was just yet another problem that my shadow was causing, and that the ability to face up to my shadow lay in my shadow.”

“I thought my social media usage was healthy and balanced and not doing damage to my psyche, too. It wasn’t until after I’d gone cold turkey and detoxed for a while that I could really see how much it had been messing with me—you won’t understand until you do the same.”

“Yeah, I thought I’d never lie to my kids, either. Give it time, you’ll see.”

To be clear: there is a sort of trivial way in which the “you can’t do that” claim is technically true in many cases. For instance, I think it’s reasonable to be skeptical of a claim of literal, absolute, perfect neutrality, from a therapist or a coach or a mediator.

But again there’s a motte-and-bailey; when you say “it’s not possible to be neutral,” you’re not actually conveying “no matter how neutral you are, there will always at least be some microscopic, infinitesimal bias present.” That’s not what most people will understand you to be saying. When you offer up the sentence “it’s not possible to be neutral,” most people will correctly interpret you to mean that there’s no way to be meaningfully neutral; that it’s not possible to be sufficiently neutral; that everyone is un-neutral in ways that substantially skew the conversation/negotiation/therapy session/whatever.

Someone who asserts “you can’t actually raise a child without lying to them” might fall back, if pressed, to something like “I’m just saying that there’s always going to be some kind of oversimplification or misleading falsehoods,” but it’s clear that most of the times that a human utters the sentence “you can’t actually raise a child without lying to them,” they mean a much stronger claim. They mean “you’re going to intentionally lie to your child, just like I did, even if you currently claim that you’re committed to not doing so, just like I was.”

V.

The fallacy of the gray is the belief or implication that, because nothing is certain, everything is (effectively) equally uncertain.

You can imagine a sort of cynical teenager who used to have a stark, black-or-white worldview—

“Things are either true, or they aren’t!”

“Some people are good and some people are bad!”

—and since has gained a little bit of wisdom and had their worldview dented or destabilized a few times, and now they sneer and say things like “everyone is flawed” or “well, you can’t ever really know anything.”

This person started out with a two-bucket belief system that proved inadequate, and their response was to replace it with an even more inadequate belief system that has just one bucket, labeled “eh, who knows?”

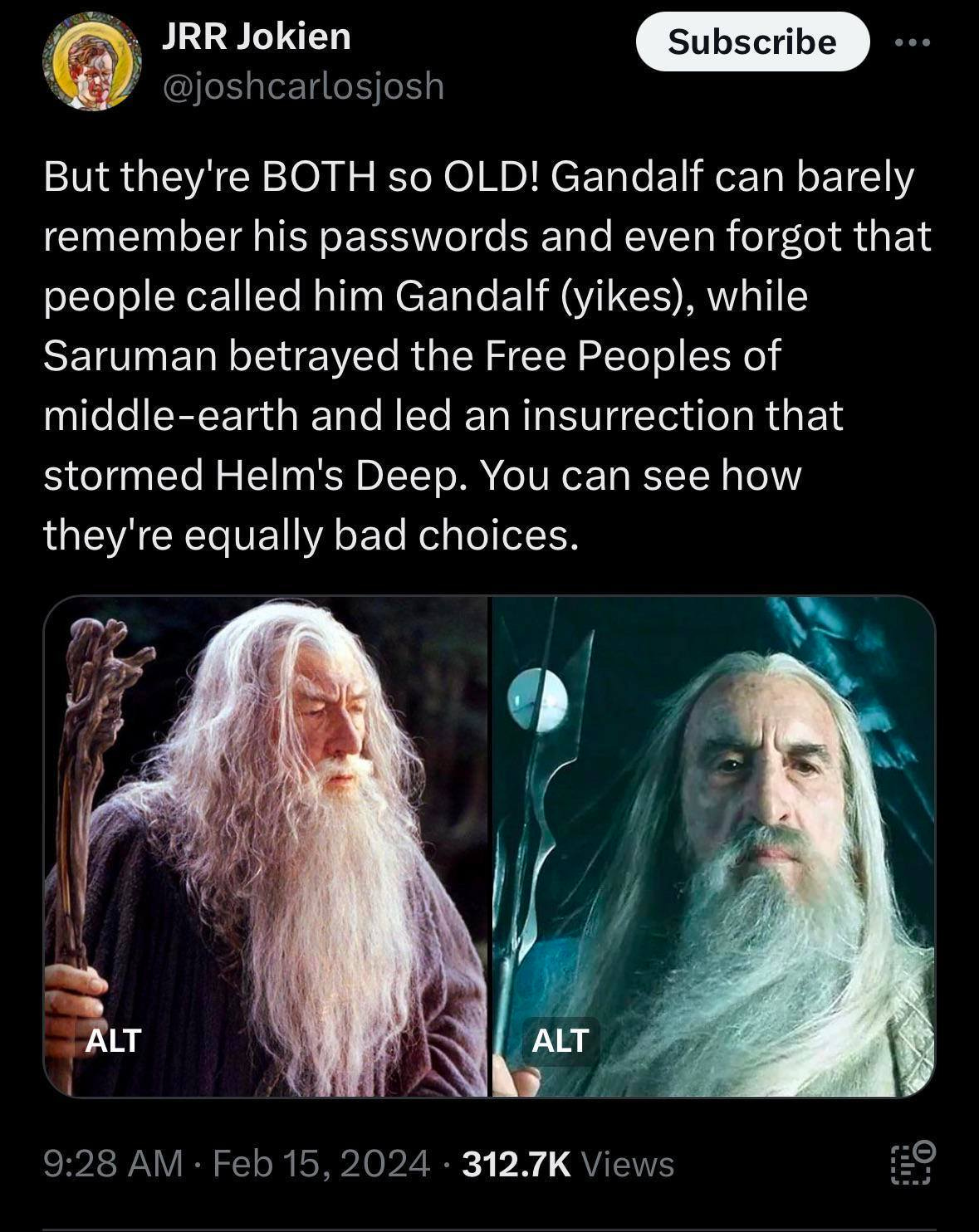

But in fact, even though everything is gray, we can nevertheless distinguish between very dark gray and very light gray. We can notice that some grays are so dark or so light that, in practice, it’s sensible and reasonable to treat them as “black” and “white.” We can take any two grays and compare them, side-by-side, and in most cases we can confidently say which one is darker.

To return to the XKCD: it’s plausibly true that no group of people can truly solve relationships, and do sex and sexuality in a literally completely drama-free fashion (though this is by no means certain to me).

But we mean something by “drama,” and it is in fact the case that some groups can (and have) basically solved relationships, and are doing sex and sexuality in a basically drama-free fashion, such that it’s reasonable for them to say, out loud, “yeah, we haven’t had any problems with drama.”

VI.

Thinking that you can do a thing which most people can’t, or that you can see a solution that everyone else has missed, involves something resembling arrogance.

But it is more arrogant, not less,

to respond to being humbled

by concluding

that everyone else who thinks similarly is just as wrong as you were. That your failure is proof that the thing can’t be done, that anyone who says the sorts of things you used to must necessarily be blind or ignorant or misguided in the same ways that you were.

False. On any given axis, some people are simply better than you—sometimes much better, sometimes jaw-droppingly better. You have to be among the literal best in the world in order for [your own failure] to qualify as [strong evidence that the thing cannot be done], and even then, it’s not as if the world never leaps ahead. In the early 1900s, the possibility of a four-minute mile was hotly contested, and many world-class athletes had tried and failed. Yet now, a promising high-schooler might run a four-minute mile and not even rate a mention in the local newspaper.

There is a correct update to be made, upon being humbled, and it does involve being (marginally) more skeptical of others’ similar claims. One should, in fact, learn from one’s own failure, and the lesson of one’s own failure is, in fact, generalizable. People can and do make similar mistakes!

But the update one makes needs to be grounded in basic, fundamental rationality. Stuff like:

The representativeness heuristic. Beware thinking that just because someone else’s claims look like yours, on the surface, they must necessarily be structured and justified in the same ways, under the hood. The mere fact of arriving at a similar answer does not demonstrate that you were both following similarly broken processes.

Different people are different. Mindspace is wide. Culturespace is wide. People have vastly different corpuses of experience and vastly different perspectives on those experiences. Some people visualize things in photorealistic detail while others have no visual imagery whatsoever. What is literally impossible for one person is trivially easy for another; what is desirable and motivating for one person is deeply aversive for another. If you try to understand and evaluate other people’s behavior by thinking about what would have to be going on inside your head in order for you to output that behavior, you will be wildly mistaken a substantial fraction of the time.

Split and commit. Every observation is evidence for multiple hypotheses; my friend telling me my hair looks good is evidence that my hair looks good, but it’s also evidence that my friend is telling a little white lie just to bolster my mood. I need to rely on other evidence to distinguish between these two possibilities, and decide which one is more strongly supported by the observation. Similarly, if I thought I could do X and turned out to be embarrassingly wrong, then your claim that you can do X is indeed some evidence that you are embarrassingly wrong, too, but it’s also evidence that you’re better than me, and I need more data to figure out which is actually going on.

If I confidently claim that I can do X, and turn out to be wrong, then I have shown that I misunderstand what it takes to do X and/or that I misunderstand my own abilities. Neither of these means that X is impossible, and neither of these means that other people must necessarily be making the same mistakes. It’s hilariously ridiculous that 12% of British men surveyed believe they could take a point off Serena Williams, but it’s also the case that there do exist multiple British men who, if playing their very best game of tennis, could indeed score at least one point.

The fact that a claim of competence is ridiculous when coming from an incompetent person doesn’t mean that competent people don’t exist.

And this is the arrogance of the recently humbled: the—

(often, though not necessarily always, self-protective)

—belief that their own failure rules out the possibility of others’ success; that if they couldn’t do it, no one can.

The replacement of an overconfident belief in their own capability with an even more overconfident belief in everyone else’s inadequacy to the task.

The unquestioned assumption that whatever flaw lay behind their own failure is present in everyone else, too—that one’s own blindness is universal and one’s own confusion is commonplace. That the warnings which they themselves failed to heed apply equally to everyone, and anyone else who ignores them is just as misguided.

The weirdly backwards progression from [thinking that they understand Domain X better than everyone else, well enough to achieve unusual success] to [being proven wrong] to [concluding that their wrongness has led to an even greater understanding of Domain X, such that they can now conclusively and authoritatively diagnose other people’s hubris regarding X, and make confident declarations about what can or cannot be achieved].

Don’t, uh. Don’t do that, please. I get that you want to help others avoid making similar mistakes—that you want to stop other people from going down the same dead ends, wasting time and effort that you wasted. That’s noble and good.

But in order to be effective at that, you have to understand what your actual mistake was, and be able to distinguish the sort of person who’s likely to be similarly vulnerable from the sort of person who’s not, and—look, this is a little bit rude, I feel somewhat apologetic, but:

You just suffered a setback as a result of catastrophically misunderstanding yourself and your own capabilities. You just showed that you don’t actually have a grasp on what it takes to be successful, in this domain. Perhaps you should respond to these events by being less confident, rather than more?

Perhaps what is indicated, given recent history, is a little bit of humility, and uncertainty, and diffidence. A little bit of productive confusion, perhaps some questioning of your basic assumptions. By all means, offer up your data and your hypotheses—if you think someone might be making a mistake, tell them.

But keep track of the “might,” please. Don’t confuse your lived experience of failure for broad domain expertise, and don’t replace arrogance with more arrogance.

What proportion of actually-extraordinary-game-changing people experienced this class of failure at least once in their life, and nonetheless became extraordinary by persisting and eventually doing something else that didn't fail?

I'm guessing something like ~75-95% for less social people in less social environments, and ~5-25% for more social people in more social environments.

It seems like less social people (e.g. high intelligence + low charisma) will have a harder time getting feedback and improving their world models, and will be like a loose fire hose, except with immense amounts of cognitive labor being pumped out in random directions instead of high-pressure water. This causes problems if it steps on toes, and the retaliating people are also somewhat smart, and occasionally arrive at mental health-related exploits when selecting optimal retaliation strategies (obviously including plausible deniability).

More social people (e.g. high intelligence + high charisma) will be able to evaluate the space and the domain, finding and surgically exploiting arbitrage opportunities, with low risk of retaliation per opportunity.