Sam Harris has a lovely little essay titled The Fireplace Delusion, in which he fairly compellingly lays out an argument that approximately everyone is wrong about something, knowing in advance that approximately everyone will flinch or squirm or lash out in various predictable ways as they encounter the argument.

(The essay is much more about the flinching and squirming than about the object-level thing.)

I, too, hold a position that approximately everyone disagrees with. Unlike Sam’s position, I don’t think it’s objectively correct, and I’m not particularly interested in convincing anyone of its truth.

But it does seem time that I laid it all out on the table, rather than just leaving little references to it here and there (as I’ve been doing for the past decade). Most of my essays set out to teach a particular concept, or persuade my readers on a particular point. This one’s different—it may incidentally end up being edifying or convincing, but really it’s more about giving you a tour through an alien mindscape that is (probably) very unlike your own.

(If you have no interest in Duncan Sabien’s particular idiosyncratic internal experience, then this will likely be a lot less interesting to you than most of my essays but probably still not zero interesting. Content warning: navel gazing.)

I. The Sculptor and the Sculpture

“You’ve changed, man,” is a pretty standard meme. It’s the sort of phrase people hurl at each other in tense moments, a common trope in movies and stories. In fact, it’s enough of a trope that there’s a pretty standard countermeme, in which people argue something like “yeah, because we’re supposed to, my dude; a life without growth isn’t a good life.”

But that’s a non-sequitur. It’s responding to a strawman. Most of the time that someone levels “you’ve changed” at someone else, it’s not because they think literally any change is bad. What they’re saying is “you’ve changed [in a way that matters, away from something that I thought we both understood to be important and foundational].” They’re claiming (whether rightly or wrongly) that the other person has changed in a way that betrays something—some promise or value or goal.

Think of a sculptor, cautiously chipping away at a mass of dried clay, sometimes daubing a little wet clay back, frowning and squinting and walking around to look at their subject from every angle.

The sculpture is constantly changing. It started out looking nothing like the final product, but slowly—painstakingly—the sculptor has shaped it, according to some particular vision.

This is a very different kind of change from, say, the sculptor changing visions mid-stream. Deciding that this sculpture is of a woman, actually, instead of a man, or an elephant rather than a person.

When people say “you’ve changed,” they’re typically accusing the other person of that latter, more drastic kind of change—of abandoning Plan A entirely, in favor of Plan B.

Of course, there’s not actually necessarily anything wrong with abandoning Plan A in favor of Plan B. It can be a bit harsh if you’ve left others in the lurch—if there were people who thought they were in Plan A with you, people who were counting on you in order to pull it off. It can be morally wrong if you’re breaking promises—but in that case, the wrongness lies in the promise-breaking, not in the switch itself. There’s nothing fundamentally bad about spending your first two years at college training to be a paleontologist and then deciding to drop out to open up a bakery.

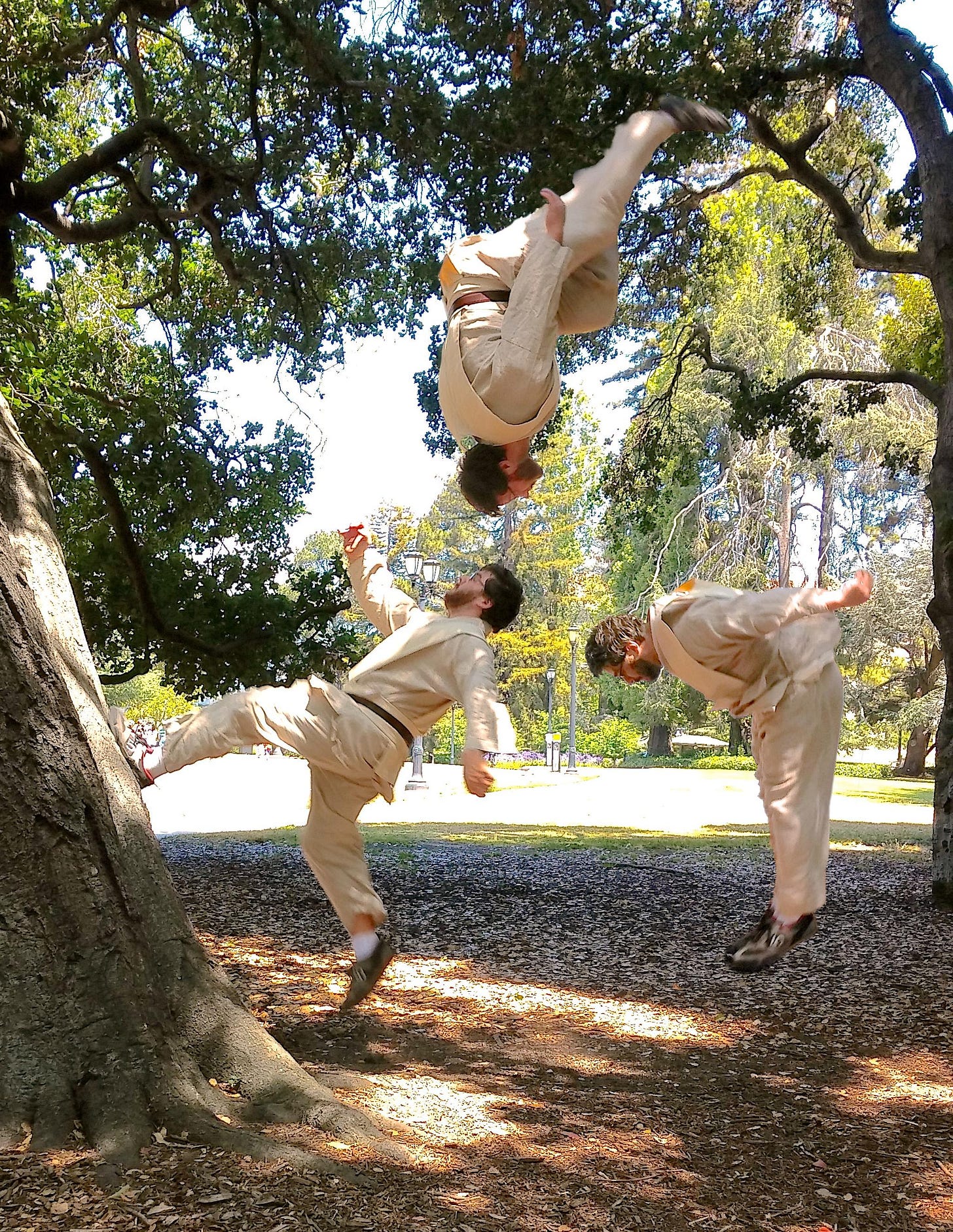

Indeed, even the shift from paleontology to baking might not be the second kind of change! When I was twelve, I saw The Matrix and assumed that the part about running straight up a wall and doing a backflip was just as fake as the bit about leaping off of skyscrapers, so I joined Lee Brothers Tae Kwon Do academy as the next best thing and spent five years becoming a black belt and an instructor.

Then I saw this video in 2004 and realized that I should have questioned several of my assumptions, and immediately set about re-sculpting various parts of my life to bring them more in line with the original vision that had previously settled for martial arts as the closest possible approximation to the thing I actually wanted.

Given the information available to him, Master Lee would have been pretty justified in saying “you’ve changed, Duncan,” but in fact he would have been wrong. I made a pretty drastic and noticeable change to my tactics, but it was just a newer, better plan for sculpting the statue I’d been trying to make all along.

I met other people in the world of parkour and freerunning who’d also come from a martial arts background, at least one of whom hadn’t been “looking for parkour all along,” and who had instead made a genuine “you’ve changed” sort of shift. He’d been actually pursuing martial arts, for the sake of martial arts, and then decided he was done with it and switched to actually pursuing parkour, for the sake of parkour. Given that it’s been over a decade, he’s presumably switched to something else, possibly more than once.

This distinction—whether it is your sculpture that is changing, in accordance with your vision, or whether the sculptor is shifting from one vision to the next—is pretty central to my worldview. A search term, if you want to go down a rabbit hole, is “diachronic vs. episodic”—diachronics are on the end of the spectrum where the sculptor changes little or rarely, and most of their growth is in line with an unchanging or only-slowly-evolving vision, whereas episodics sculpt themselves into one statue after another after another, changing the very criteria for success.

Something I’ve done some twenty or thirty times is ask a room full of people a question that goes something like “hey, so—how long have you been around? Like, not when-were-you-born, but the you that is standing before me today, like if this is Version 3.4 of you or whatever, when was the shift from 2.7 to 3.0? When did this version of you come into being?”

And when I do, there’s invariably a couple of people who say something like “two weeks” or “yesterday,” and there’s invariably a couple of people who say something like “twenty years ago” or “when I was born,” and both types tend to look at the other like

…because, in many cases, neither type even realized that you could live life the other way.

(No, I couldn’t’ve used Shocked Pikachu there because Shocked Pikachu strongly connotes that the shocking thing is a predictable consequence of your own choices, not just something generically surprising.)

I’ve been working quite hard in the above to present this dichotomy—

(between changing sculptures and changing sculptors)

—in value-neutral terms because I’m actually extremely partisan, on this question; you’re looking at Duncan version 1.37; there has never been an update to 2.0 and that is very much on purpose.

II. A Tragedy In Four Parts

III. Someone Else’s Statue

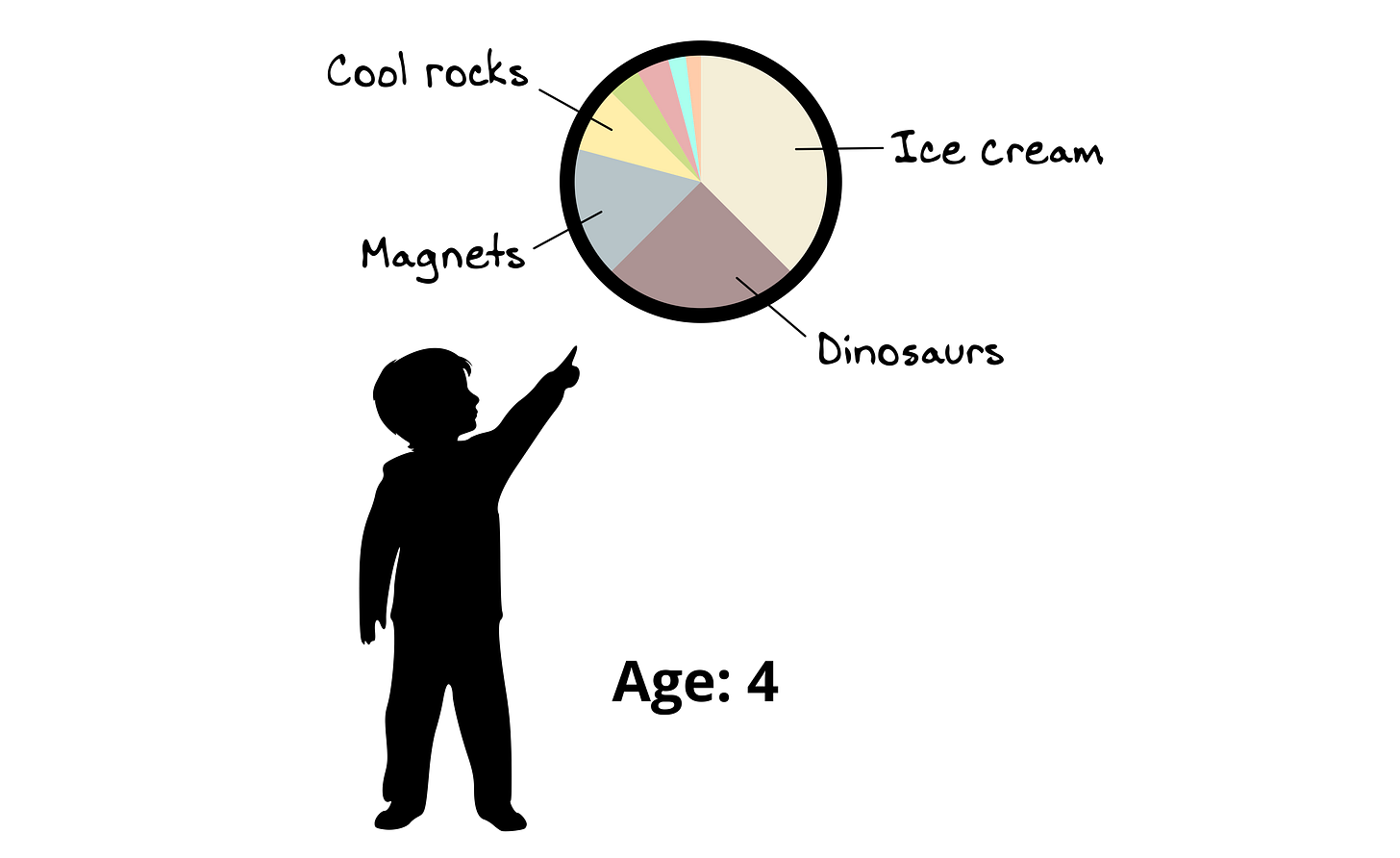

I was not at all fond of the shift that took place over the course of the last two images.

I had no problem whatsoever with the shifts that took place between the first and second, and most of the shifts between the second and third, because those were changes to my sculpture, in accordance with my vision. The shift from magnets to dinosaurs to LEGO spaceships was one of operationalization; each of those interests were in pursuit of the same fundamental goal of a certain kind of awesomeness. None of them were exactly the thing in themselves, but they were pointers to the thing, portals that let me access it (or at least catch glimpses of it).

Drew was also a pointer and a portal, which is part of why the whole thing was so disorienting. Some people help you to be more yourself, drawing out the best in you and making it easier to act in accordance with your highest values, and when two people each do this for the other I call it “being friends.”

But Drew’s penis was not a pointer and a portal to the same target as magnets and dinosaurs and LEGO spaceships. Drew’s penis had approximately zero to do with the things that I cared about and was (fumblingly, naively) optimizing for. Instead, it was part of this whole new alien value system that had been grafted on top of my own, imposed upon me without my consent.

This is the part where, like Sam Harris, I expect to lose a lot of people.

(Lose in the sense that you’ll be like whaaaat? No. I’m not expecting many people to, like, give up in disgust or anything like that.)

Puberty? Bad, according to me. Sex? Bad, according to me.

The perspective from which they are bad is the perspective of a diachronic sculptor who already had a good thing going on. Someone who already had reflectively endorsed values, and already had a plan of sorts, and was making some kind of progress on carving the sculpture, even if that progress was inept and inefficient.

I was already a person, in other words, and neither needed nor wanted a bunch of new priorities to be shoved down my throat. It’s as if I took you, today, and strapped you down to an operating table and injected you with a cocktail of drugs and hormones and retroviruses that would cause you to have a sudden, deep, and distracting interest in, I dunno, licking spheres of various sizes and textures—a hunger to find and lick spheres, a need to do so, such that if you did not, your quality of life would fall and your mental health would begin to noticeably deteriorate—an addiction to licking spheres, driven by a brand-new superstimulus that you’d never felt before, a pleasure unlike and more powerful than anything you knew up to this point.

(Oh, I should mention that this cocktail will also cause you to, like, secrete mucus all along your spine and make your feet swell to twice their size and turn anywhere between a tenth and a third of your skin purple.)

And this desire to lick spheres would tug at you, like a whirlpool, like a black hole. You’d be happily going about your business, and then you’d see a thing that was maybe a sphere out of the corner of your eye, and suddenly your attention would be yanked to it, dragged to it, even if it wasn’t a sphere you’d now be thinking about spheres again, regardless of where your mind had been five seconds earlier, and this would happen to you all the time for the rest of your life.

You, uh. Would probably be mad at me.

You would probably be mad at me, if I did that to you. If you took me to court, you would probably win, in no small part because you would be able to gesture to your previous life, in which you didn’t have to spend 5-35% of your time thinking about and seeking out spheres, and convincingly argue that I had ruined it. That you were now compelled, against your will, to spend a large fraction of your time and energy on an activity not in accordance with your true values. That you were now crippled in your ability to sustainably focus on the things you cared about.

Licking spheres (probably) has nothing to do with the vision of your sculptor. It has nothing to do with the relationships you want to build, the things you want to create, the experiences you (currently) long to have. It’s probably not directly contra any of those values, but it takes away from your finite supply of motive energy. By running this procedure on you, I’ve sort of cut your effective waking hours down from sixteen to twelve, which is a big hit.

Lots of people—most people?—do not, uh, get their shit together prior to the age of ten. Lots of people do not settle upon a vision prior to the age of ten, and among those who do, not many of them still endorse and adhere to that vision twenty or thirty years later.

And so, for most people, the curveball of puberty is … disorienting, sure, but it’s not derailing, because there weren’t exactly rails to begin with. Just blueprints, sketches, a vague idea of where the tracks might go. By the time the rails actually get laid down, they’ve had time to adjust to the new paradigm. Plans get made in a way that takes the hormones for granted, treats sexuality as part of the background of the game.

But I am not most people! For me, ice cream got taken for granted, as part of the background of the game. Rollercoasters and trampolines and swings got taken for granted. The radness of neon colors and the excellence of John William’s Theme from Jurassic Park and the boyhood conception of loyalty and honor as set forth in stories like Star Wars and The Sandlot.

The desire to stuff sweet things in my face hole is every bit as biologically predetermined as the desire to stuff Drew’s penis1 in there, but it was there first. It’s every bit as orthogonal to my deep and enduring values, but I had already taken it into account, and compensated for it.

It’s the difference between getting 100 hours into a game and suddenly, out of the blue, being forced to adopt a completely different set of objectives and a brand-new controller layout, versus finding out, during the play-through tutorial, ah, okay, this game actually has a couple of very different subthreads running through it, I’ll need to switch back and forth sometimes. Got it.

IV. Interlude: A Failure to Factor

My previous employer, the Center for Applied Rationality, developed a mental technique called goal factoring that was designed to help people recognize bad plans and lost purposes (and then fix them).

Basically, the idea is that humans often find themselves chasing their values pretty darn inefficiently. They want to make their parents happy, so they go to medical school, like their parents always wanted, without ever really pausing to ask themselves whether [their parents’ happiness] is really worth the cost being paid. Goal factoring asks: maybe is there perhaps some other, cheaper way to purchase some measure of happiness for your parents, that doesn’t cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars and many years of your life?

Few people sit down and consciously decide, yeah, okay, I will burn my whole career in order to make Mom and Dad happy. Instead, the decision is made up of a thousand little flinches, a bunch of little sad looks and side comments and narrative framings that eventually snowball into you doing a thing that you wouldn’t have consciously chosen (but now it sort of feels Too Late and it would be Awkward to upend your whole life, the default has been set and oh well—)

It’s pretty easy for humans to lose track, in this way. To end up with this sort of misalignment between means and ends. To forget, or be somehow incapable of noticing, that there are other ways to get the job done—ways that are sometimes 10x or 100x or 1000x cheaper or more efficient.

I mention this because frequently, when people hear me say the whole sex thing is pretty bad, actually, they respond as if I am saying that intimacy is bad, or that procreation is bad, or that orgasms are bad.

Nope! None of those things!

Intimacy is great, but you’re fooling yourself if you think that doing slimy pushups against each other is the optimal way to produce it. It may (sadly) be one of the best ways in practice, given what nature has left us with, but that’s very different from saying “yes, this is definitely how a good designer would have designed this system from the ground up.”

A literal actual majority of the people I’ve talked to about this genuinely claim to believe that yep, this is the right way for intimacy and pleasure to be created, it’s ideal, no actually better system could exist, any major changes would be worse.

(And—I’ve checked—they are not making a pragmatic argument à la “no actually better system could have been produced by the blind idiot god of natural selection.” They’re not talking about taking humans as they presently are, and working within existing constraints. They really actually mean that there just isn’t any better way. That, if you want to set out to create intimacy between people, the objectively correct way to do it is to route it through physical proximity with lots of goo and poking and pulsing. That physical proximity with lots of goo and poking and pulsing is the appropriate process for producing intimacy, just as going to med school is the appropriate process for making your parents happy.)

And they are deeply confused. You are deeply confused, insofar as you are (probably) a part of that majority. People laugh at the naïveté of an eight-year-old who points out that French kissing is weird and gross and stupid, but it’s because they’ve allowed the hormones to gaslight and frogboil them and over the course of years and decades of brainwashing they’ve lost the capacity to see that the eight-year-old is just straightforwardly correct.

French kissing is weird and gross and stupid. It produces a good result—pleasure and bonding—but that’s because we’ve optimized within a broken system, like somebody who’s learned to wiggle the wires and place their phone just so to make the charger cable actually connect. There’s a vast difference between “this is the best we can manage, given constraints,” and “this is actually unambiguously good.”

I’m quite fond of orgasms, as it happens. I wouldn’t write them out of the universe. I just wish they incentivized me to do something that I straightforwardly want to do, rather than incentivizing me to:

Sit alone tediously massaging a body part, instead of doing anything actually interesting

Try to convince some other cool and interesting person to drop all of their cool and interesting activities to do some slimy pushups with me

It’s analogous to how I’m quite fond of cookie dough, but obviously it would be better if my tongue responded to broccoli and boiled chicken with the same enthusiasm.

A lot of people embrace a naturalistic fallacy that because this is how we’ve evolved to be—because puberty and sexuality are destined to blossom and unfold within us—they are somehow correct and good, as a result.

But I don’t buy that something is optimal just because it happens to have survived the selection process; death is natural, too, as are parasitic flies that lay their eggs in the eyes of children, and I don’t like those things, either.

(Sorry. I’m leaning a bit too hard into trying to argue for this viewpoint, but that’s an artifact of having previously had to defend this viewpoint, against people telling me I’m wrong and then having really really really really dumb reasons for thinking so. I’ll stop, and get back to just … describing what’s true inside my head.)

Someone on Facebook once asked me what I would hook orgasms up to, if I could rewire the human reward circuitry, and my first answer was “these kinds of wishes go badly in subtle ways; you shouldn’t take my offhand guesses as if they are Genuinely Good Ideas.” I would want to think long and hard and run a lot of small experiments before I ever pressed a button to change how things actually work for humans, because even though the current equilibrium is hella dumb it is reasonably well calibrated for thriving in the existing environment. Most shifts away from the evolved default would make things much, much worse.

But if I’m in a happy hypothetical with a genie who’s actually on my side and not trying to trick me, some places where I might start include

Make orgasms happen whenever you experience awareness that you’ve achieved a difficult goal. If there were some biological subsystem that tracked progress toward “I’ll study for two hours every night until I understand the material” and offered me commensurate pleasure as I went, culminating in a big burst of pleasure when I finally succeeded, this seems like it would be pretty useful.

Make orgasms happen when you meaningfully aid another person—whenever you help somebody out of a hole that they couldn’t have helped themselves out of. (Here I’m thinking of everything from rescuing victims from bullies to handing food to homeless people to joining in collaborative projects.)

Make orgasms happen when you actually understand another person, as verified by their agreement that you do. People talk about how sex brings people closer together, and it does, but like, come on, there are a lot of ways to be closer together that are WAY more meaningful than “we squirmed around in physical proximity and breathed in each other’s faces.” If we experienced sexual reward from mutual understanding, this would foster a lot more curiosity and intimacy and openness.

Relatedly, make orgasms happen when you share vulnerably with another person and they share vulnerably with you.

Make orgasms happen as a part of the process of creation. Make it so that art and architecture and welding and writing all come with additional reward, so that there’s A Little Something Extra pulling you across the finish line.

Make orgasms happen when you’ve physically exerted yourself in a healthy way. If running one mile was pleasurable like the first minutes of sex and running five was pleasurable like the end of it, it would be a lot easier for most people to stay fit and active.

… again, none of these are actual proposals; none of these are actual good ideas. But I think they serve to demonstrate that there are much better things to reward than “we took off our clothes and slimed each other.” A clever ten-year-old could come up with dozens of better ideas, to optimize for ten-year-old values, and the parts of human values writ-large that are missing from the ten-year-old’s perspective are deeply sus and mostly not the sorts of things we would freely choose, if we were starting from scratch.

V. “idk, Duncan’s not not trans, exactly…”

It’s largely an aside, and not particularly central to the main thrust of this post, but it feels like I “should” mention, at this point, that my FB avatar is not an actual photograph of my actual body, but rather a picture of this guy:

… who, I’m told, is a character in a movie I haven’t seen. I didn’t pick him to be my avatar for that reason; I picked him to be my avatar because when I first saw a picture of him I recognized myself. If you were to plug me into the Matrix and I were to pop up in the whitespace of the construct program, I wouldn’t look like a big fat old guy with chest hair and a beard and big meaty hands, I would look like a kid with red hair and glasses because that’s what it feels like to be me, on the inside. If there were a button I could smash to transform myself into this sort of body, I’d smash it immediately, even if it made things like employment and driver’s licenses and romantic relationships much more complicated.

i.e. it’s not just puberty’s imposition of a new and unwanted value system that I object to; I also object to how my body was forcibly and horrifically mutated, against my will, in a way that involved qualitative change and not merely continuing to grow as I had prior.

Figured I should go ahead and mention that, in case the rest of this wasn’t weird enough. :P

VI. Okay, so, what—you’re just gonna be sad and bitter all the time?

Nope! In fact, originally this essay was going to be titled either [Surrendering Without] or [Making Peace With The Beast], and it was going to focus on the particular compromise that I’ve struck with sex and sexuality and puberty and all that, because I thought that maybe the mental motions I’ve made in this domain could be repurposed by other people, for their own intractable problems.

But that seemed a little presumptuous and also the required background was greater than the content, so the essay morphed into this, instead.

Suffice it to say: given all of the above, it would be pretty reasonable to predict that I have a twisted, tangled-up, unhappy relationship with my own sexuality, full of angst and resentment and suffering. Many people have predicted this, explicitly.

But I don’t! I have what several of my partners have described as a “surprisingly” relaxed and healthy orientation to sex—in many cases a more relaxed and healthy orientation than they have, even though most of them conspicuously lack my particular grievances.

The way I got there is pretty straightforward, I think. An important chunk of it is written up in the essay Lies, Damn Lies, and Fabricated Options, which is about not tricking yourself into thinking that eat-your-cake-and-have-it-too options are actually on the table.

If I were in fact to strap you down and put you through the licking-spheres procedure, you would leave the operating table genuinely desiring to lick spheres, and you would get real, actual pleasure from doing so, no matter how much you wished that weren’t true. Probably, the rest of your life would look very different, but it’s not necessarily the case that you should fight tooth and nail against your desire to lick spheres, as opposed to simply making the best of the hand you’d been dealt.

(This is especially true if it’s not clear whether you can simply resist, or whether attempting to do so actually just sets you up for cycles of bingeing and guilt.)

You should be mad at me, the asshole who did this to you. But given that it’s done, you should probably go ahead and plant both feet in the world where This Is Your Life Now, rather than sort of pretending that you can plug your ears and lalalalala your way back to the life you had before.

Or, to put it another way: if you cannot find joy in the compulsory sphere-licking impulses, you will have less joy in your life but the same amount of compulsory sphere-licking impulses.

It would be silly, I think, to refuse to accept the reality of the situation, especially given that there is real, actual pleasure and real, actual relief to be found in sex (not to mention the pretty darn relevant fact that most of the other humans are operating on this wavelength, and so even if I’m holding myself aloof in some philosophical sense it’s pretty important to be able to play this particular game, and play it skillfully (and lightheartedly)). I very much wish that the alien value system had not been imposed upon me, but it was, and there isn’t really a viable way to ctrl-z things, especially not without undermining the foundations of the life I’ve put together in the decades since.

Thus: I take from life what sighs and shivers and orgasms I can get, and I get down in the goo with the people I love so that we can reap the benefits of goo-getting together. I work with what reality gave me.

But one thing I don’t do is …. “go native”? “Give in”? I think it would be silly in a different way to forget that I was, in fact, violated and mistreated by my biology, and gaslit and frogboiled by my fellow humans. I think that I can embrace what is without going all the way to total acceptance; I think that I can wring value from the sphere-licking without in some deep sense becoming a sphere-licker. Most people have some combination of [amnesia] and [willingness to betray their past self’s values] that is sufficient to cause them to expand their self-definition to include sphere-licking.

I don’t, though. I continue to (correctly, I think) recognize my own sphere-licking as something like a necessary compromise, forced upon me from without. I incorporate it into my statue-making inasmuch as I have to, but I don’t forget what the statue would have looked like, if my own artistic vision had not been warped by coercion.

What this looks like, in practice, is sort of the opposite of heel-dragging and resentment. In the moment, it’s not my partner’s fault that we’re both caught in this web, and in the moment there’s no point in half-resisting and half-acquiescing. When I decide that it’s time to lick spheres—

(Either because I’m with a partner who speaks that language and I genuinely want to meet them where they are, or because it’s simply time for a dose, to dispel the built-up need and hunger that will otherwise get louder and louder and eventually drag me in the wrong direction)

—I lick with gusto. Anything else seems … partial? Tunnel-visioned? Low-perspective?

Silly. It feels like fighting myself. Like shooting myself in the foot. Given that this is the body that I have, that these are the urges that body produces, that these are the needs dictated by my particular hormonal makeup and that I am unlikely to substantively change that makeup—

Given all of that, the obvious solution seems to be to whole-ass sexuality while I’m engaging in it, try to reasonably minimize how many minutes of each day it takes up, and otherwise just get on with my life.

Biology took my waking hours from sixteen down to twelve, metaphorically speaking, but that doesn’t mean that I should take myself from twelve down to ten by sulking. That’s basically letting the terrorists win.

By the way, I’ve sort of glossed over the fact that having a sexual awakening involving a boy introduced a whole other layer of headache, but indeed it was not Simple to be anything other than straight in suburban North Carolina in 1999.

For what it's worth, while my experience of puberty was very different, I think all of this makes sense and you didn't lose me at any point.

Thank you for the post, I recognize quite a bit from it even though it's not a 1-on-1 match. I definitely remember being disgusted with how my body and my mind were changing during puberty, and that feeling of disgust lasted for a long time after. I am happy that afaict it didn't change any of my fundamental values I had when I was 10, and that those only became deeper and more explicit over time.

BTW, I know it's kind of bad form to id other people but it sounds like you are transage (https://transage.info/), would you agree?