Author’s note 1: There are several preexisting essays that sort of dance around the point I want to make here. One of them is Scott Alexander’s excellent The Categories Were Made For Man, Not Man For The Categories. Another is Eliezer Yudkowsky’s sequence titled A Human’s Guide To Words, particularly the essays Taboo Your Words and How An Algorithm Feels From Inside. Another is Logan Strohl’s Patient Observation, part of a sequence on Naturalism. Yet another is Collin Lysford’s Representation and Uncertainty. I’ll be drawing on and possibly explicitly referencing some of my own points from previous pieces.

But none of the things I’ve previously read or written seem to me to come right out and just … point directly at the mistake, and clearly state an alternative, in a way that would make a precocious twelve-year-old nod and go “ah, okay, got it.”

So, my apologies if you’ve already put this one together yourself (and thus none of this feels revelatory), but at least now there’s a primer to point to. This is (trying to be) a rationality 101 essay.

Author’s note 2: this essay takes its time strolling through the landscape, and it does so on purpose, for what I consider to be good reason. I didn’t put a concise thesis statement up front because in this case I think that would leave the reader genuinely less likely to come away with anything new and valuable (c.f. sazen, c.f. idea inoculation). But if you absolutely must have the abstract as an appetizer, you can ctrl+f The problem: and then come back to the top.

Content warning: mentions of SIDS

I. Belief

Most people do belief in a way that feels really alien to me.

I don’t feel capable of (for example) believing that my preferred sports team or political candidate is going to win. I don’t feel capable of believing that the weather will be nice tomorrow. I don’t even feel capable of believing that the next marble out of a bag that’s 95% red marbles is going to be red.

(I also don’t feel capable of professing those things, while not really actually believing them, which is a thing people do for all sorts of reasons like fitting in or inspiring others or motivating themselves or avoiding thinking about scary stuff or whatever.)

Belief doesn’t feel like a thing that I do. It’s not a choice. It’s not even an action. It’s just … the state of reality, to the best of my ability to perceive and understand it. It’s something I discover.

To the extent that I have a belief about the bag of marbles, it’s “well, as far as I know, 95% of the marbles are red, so the next one is probably going to be red, and if there’s a string of, like, ten non-reds in a row then I’m going to start getting suspicious.” It doesn’t feel like I could believe something different from that, via an act of will.

(“Just trust me!”

“Um…”)

Crucially, basically all of my beliefs are probabilities, even the ones that are easiest to express with absolute-sounding language. I do occasionally say sentences like “I know that the sky is often blue during the day,” but the word “know” is shorthand for “really pretty confidently believe, since I’ve seen it a bunch of times, assuming I’m not colorblind or crazy and I’m not being tricked by the Matrix Overlords or something.”

I try to keep my pedantry down to a tolerable level, so I leave off those disclaimers a lot of the time, but they’re always there if anyone feels like double-clicking.

II. You keep using this word. I do not think it means what you think it means.

You can do words and concepts in an analogous fashion.

(You should do words and concepts in an analogous fashion, according to me. I think it’s a better way, just as I think my way of doing belief is better.)

What do I mean by “concept”? Here are a dozen examples:

Chocolate

Narcissism

Country music

Male / Female

Abuse

Gay

Reasonable

Green

Alive

Friend

Trying

Vegetable

I think that most people, when they come into contact with/try to use words like those in the list above, do a wrong thing that is similar to the wrong things people do with their beliefs.

By “wrong,” I don’t mean that they fail to communicate. Most people use words the way that humans use words, and so the problem isn’t about confusion between individuals (I’ve got a different essay on that).

Rather, the problem is that most of the time both of the humans involved in the conversation are confused in the same way, and thus neither of them notices. You are probably using words wrong, in the sense that you are doing a (very normal and commonplace) thing that just … fundamentally doesn’t line up with reality. It’s wrong in the same way that Newton’s laws of motion are wrong.

(Newton’s laws of motion get you pretty darn close, to be clear, and that’s part of the metaphor! It took a long time for us to notice that Newton’s equations were off. The problem I want to point at is subtle. If it were bigger, more people would’ve noticed it, and I wouldn’t be writing an essay to explain it.)

III. _______________

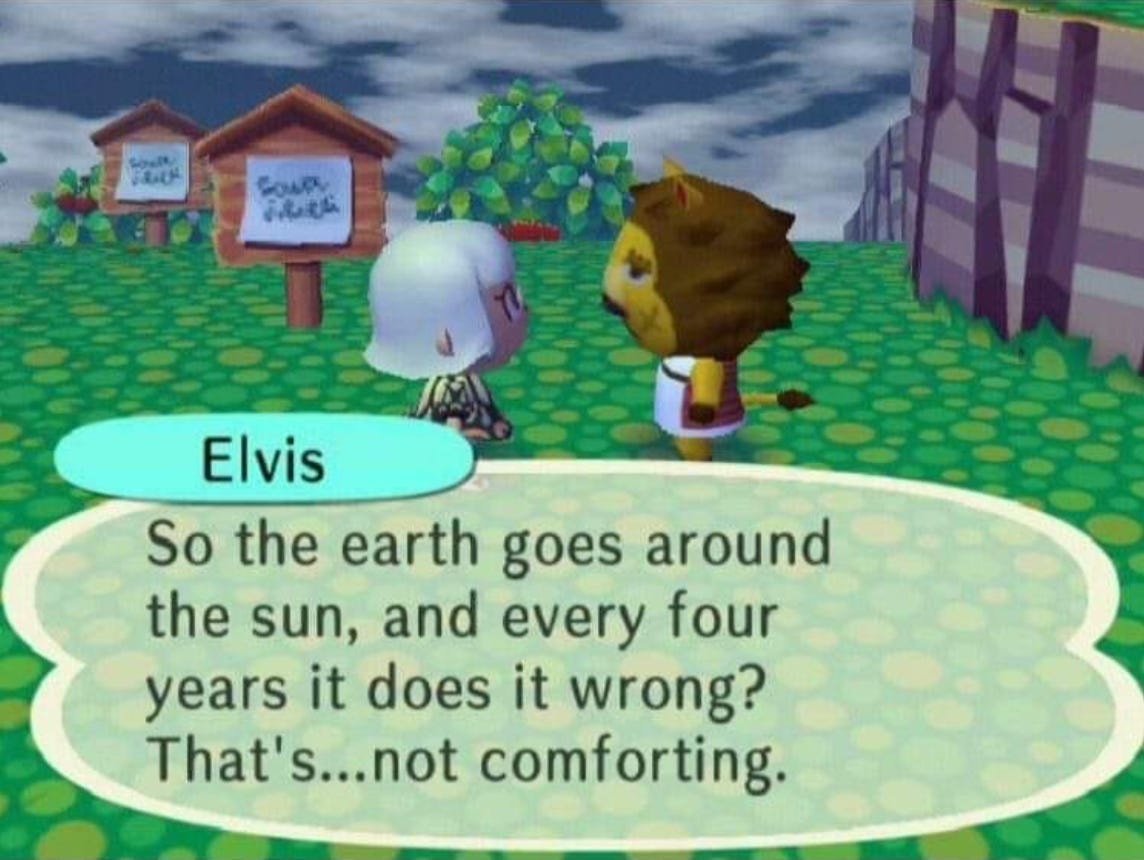

In another timeline, this essay was titled “White Chocolate Is Not Chocolate, Because Nothing Is Chocolate.”

In another, it was titled “Pshhhh—As If ‘Gay’ Is Even A Thing It Is Possible To Be.”

In yet another, it was titled “No True Scotsman Is Not A Fallacy, It’s Simply How The World Actually Works.”

(Sorry, this is all rather more loose and extemporaneous and beat-poet than most of my essays are. Think of this as a buffet of thoughts that you’re sampling, and do not take rigorous notes; the point is the gestalt and there’s a concise recap at the end.)

IV. Strange Attractors

Imagine you are a boy, and over the course of your first few years after puberty, you notice attraction to:

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

“Aha,” you say, quietly, in your own head. “I see what’s going on. I, as a boy attracted only to girls, am Straight™.”

To be clear, this is a completely justified and reasonable conclusion. What does “straight” even mean, if not “consistently and exclusively attracted to the opposite sex”?

Over the next few years, you notice attraction to:

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A girl

A boy

A girl

“Wait, what? But—but—but I’m straight!”

This is the problem I’d like to point at, in a nutshell.

What has happened here?

(This line inserted to give you a chance to form your own thoughts, if you feel like it.)

There are a few different ways to cut at the mistake.

One way is to note that binaries are more-or-less fake. There are things out there in reality like, say, copper atoms, which have a single defining characteristic (29 protons in the nucleus) and are basically unambiguous—something either is a copper atom or it isn’t.

(Let’s not fret about isotopes.)

But most things are more like, say, chairs, in that there are some things that are pretty obviously chairs and some things that are pretty obviously not chairs and a surprisingly large number of things that are kind of chairs, or maybe chairs, or very weird chairs, or definitely not chairs but with a few oddly chairlike properties.

And “straight” (as well as “gay” and “bi”) is much more like “chair” than it is like “copper atom.”

Another way to model what’s gone wrong is to note that “straight” was an accurate label or summary at the time it was applied, but that data collection continued. If you’re polling 1000 people, the first 100 you poll might be non-representative in any number of ways, and that limited data set might lead you to different (and less accurate) conclusions than the ones you’ll draw at The End.

There’s nothing wrong with having a preliminary or tentative label, of course. The problem with our hypothetical boy is that his label has taken on a life of its own—what started out as a post-hoc description has become an inflexible prescription. Somewhere along the way, he forgot that “straight” came from simply looking at reality and reporting what he saw, and it became a Thing that he is now failing to live up to. By having his heart flutter at the sight of another boy, he hasn’t discovered that he’s straight-with-an-asterisk, or bi, or whatever—he’s discovered that he’s a bad straight person, a flawed straight person, a messed-up, broken straight person.

The standard rationalist-flavored advice “keep your identity small” is meant to protect people from this sort of crisis—

(And it is a crisis, for many people. This sort of experience—a sudden, disorienting, unprecedented attraction—causes very real distress for people. And that’s not only because our society is particularly tangled-up about sexual identity. Similar disruptions occur when people unexpectedly find themselves liking or disliking math or poetry or broccoli or Star Trek, or suddenly gaining or losing faith, or coming into conflict with their fellow Xicans or Ymocrats, or receiving an injury that changes what they can do with their mind or body, or waking up the morning after impulsively stealing or cheating on their partner, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. Experiences that are discordant with one’s preexisting self-image can and do throw lives into chaos—not always, by any means, but certainly often enough that we regularly use the word crisis1 to describe it.)

The standard rationalist-flavored advice “keep your identity small” is meant to protect you from just such a crisis, but I think that advice doesn’t go far enough.

Similarly, it’s become fashionable in certain circles to disdain arguments that are “merely semantic,” and to look down on people who fight over whether a tree falling in the woods with no one around to hear it makes a sound or not, and I think that, too, is not going far enough.

Both of these snippets of advice (technique?) are cutting at different upshoots of the same weed, and it needs to be pulled up by the root.

Looking in on the humans from the outside, it seems to me that whenever they create a new conceptual handle like “gaslighting” or “sealioning” or “feminism” or “censorship,” they immediately become more concerned with the shape and scope of that handle than with the reality it was invented to gesture toward in the first place.

(And with winning fights over how the handle is used, because its usage comes with consequences and those consequences change who has power over whom.)

But all of that is getting lost in the weeds. And the whole enterprise rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of what words/concepts even are.

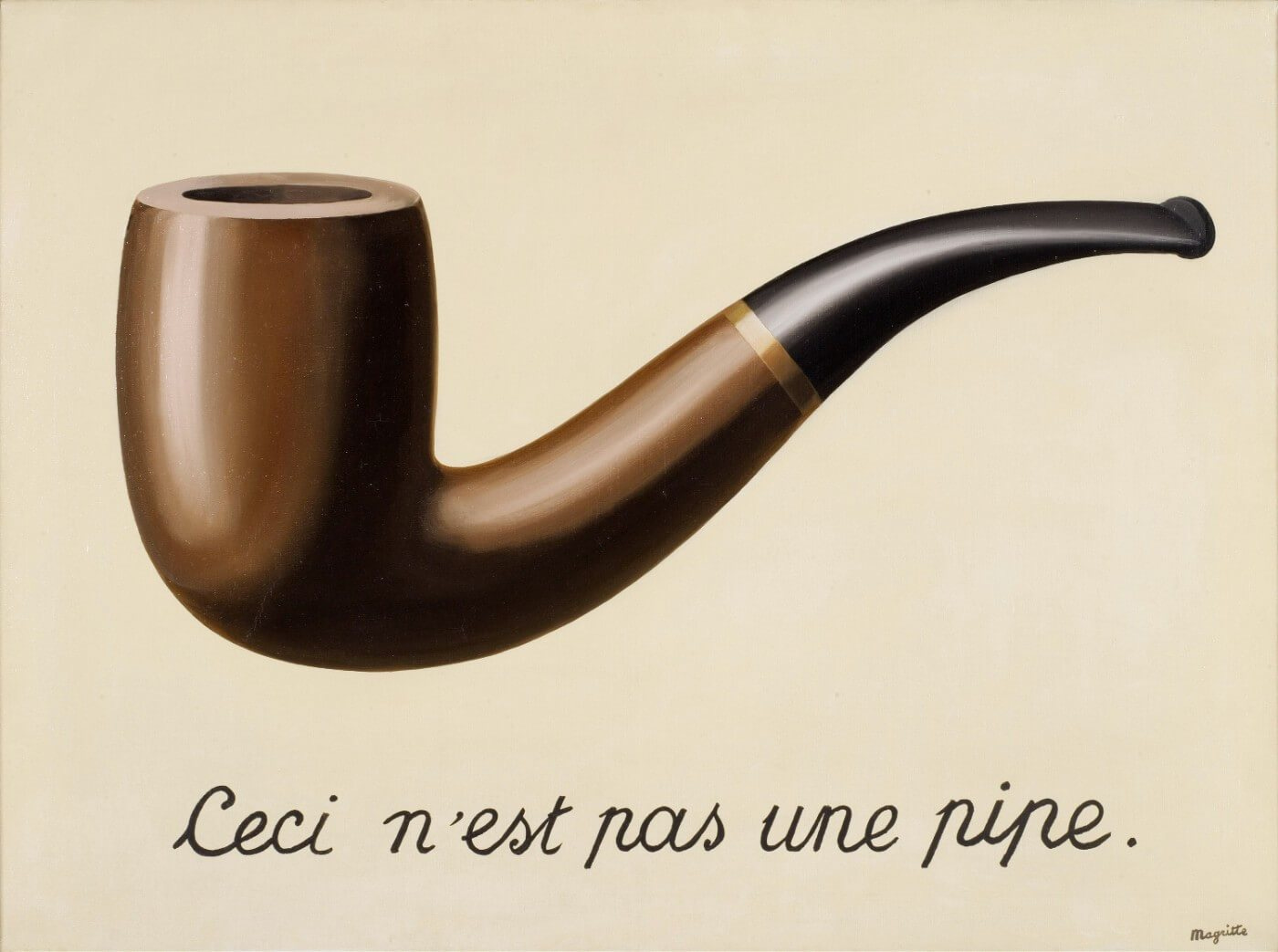

V. The Treachery of Plato

There are, in fact, copper atoms out there in reality.

Separately, there’s the word/concept “copper atom” that we made up, to refer to them, and that word/concept is not made of the same sort of stuff as the actual copper atoms themselves.

What about the word/concept “square”?

Are there squares, out there in reality? Do squares exist, in the same way as copper atoms?

I would argue that there aren’t squares out there—that squareness is a quantity, not a binary, sliding from “basically not at all a square” to “as perfect an instance of a square as we are capable of making or measuring but let’s not kid ourselves, there are jiggering imperfections down at the quantum level, this is a square but it ain’t a Square™ because squares don’t actually exist, in the same way that 1 is not a probability.”

I often speak in ways that effortfully track subtle or unusual distinctions, and one of the quirks of my dialect is that I’ll sometimes say a sentence like:

“This is exactly the sort of thing that people invented the phrase ‘strawmanning’ to describe.”

I didn’t start doing this for any specific, memorable reason. It just sort of slowly crept into my speech. But I like it. I like it because it prevents me from forgetting that strawmanning isn’t a thing. It isn’t a thing in the same way that squares aren’t a thing.

The way the word “strawmanning” ended up in my head is, there were a bunch of real actual events that took place, and a bunch of those events had some characteristics in common, and at some point some people felt like it was important-enough that they be able to gesture at and talk about that commonality that they invented the label “strawmanning” to mean “that thing that’s going on here and here and here and here and has properties X, Y, and Z” and the label was useful enough that it stuck and was adopted by other people and now here we are.

From a distance, all those little individual dots look like they form a solid shape. But there is no shape. There’s just a bunch of dots that all share a color. There are things out there in reality that have a lot of the property which we call “strawmanning,” but saying “X just is strawmanning” feels like it’s leaning toward the same sort of deep-seated confusion as “but but but I’m straight, though!”

(I still do it sometimes. #workinprogress #icontainmultitudes)

Strawmanning, and straightness, and squareness, and chocolate-ness, and so on and so forth—none of these things are things in quite the same way that copper atoms are. They’re more like constellations than like stars—they’re associations, collections of traits, nearnesses and similarities. When someone says “white chocolate isn’t chocolate,” it’s because they’ve lost track of the fact that Chocolate™ doesn’t exist. There is no hard line separating Definitely Chocolate from Definitely Not Chocolate—you can unambiguously distinguish, say, a confection made with cacao solids from a confection made with only cacao butter, but the very fact that people feel they have to fight over whether the latter is or isn’t “chocolate” is evidence that the answer doesn’t lie in plain sight. People don’t fight over what is or isn’t a copper atom because that would be boring, because “copper atom” is a lasso that neatly separates an unambiguous set of things from everything else in the universe, using a single noncontroversial criterion.

“Chocolate” isn’t like that. It’s more like, I don’t know, “golden retriever,” in that it’s a cluster that has some clear, central examples and some clear non-examples and a fair amount of internal variance and some pretty sharp boundaries but plenty of places where things get fuzzy and porous and convoluted.

VI. The perception of color is always mediated by context

Yes, there is in fact a way that the dress actually is, under pure white light, and sure, it’s worth investigating to find out what that is. But it’s interesting because our perception of the dress in the photograph is so confusingly ambiguous. It’s an optical illusion found out in the wild, and it would be neat to understand how it came about. But there simply isn’t an answer to the question of what color the dress “really” is, in the photograph. The answer is that the dress in the photograph is ambiguous.

(And doing things like taking a single pixel and blowing it up to fill the screen and then color-sampling it to find out its hex code are a distraction because that’s not how our vision was perceiving those pixels anyway.)

VII. Please select all squares containing a stoplight

Copper atoms are a single point in thing-space.

Squares exist on a line stretching from (almost) “0/false/no” to (almost) “1/true/yes.”

Chocolate kinda seems binary at first glance but when you start digging into it it quickly becomes clear that there are at least two or three defining attributes and probably more.

There are some concepts that have five defining attributes, or a dozen, or it-takes-at-least-four-off-of-this-list-of-twenty-but-it-can-be-any-four-and-also-some-of-the-items-are-literal-opposites. And the more complexity you have baked into the concept, the harder it becomes to draw a line that clearly and unambiguously captures every example and leaves out every non-example. There are just a lot of different ways for something to be sort of a chair.

(e.g. what if it was a chair, and I smashed it? It doesn’t have legs anymore. You can’t sit comfortably in it anymore. Is it still a chair, just with the additional modifier tag “broken,” or is it not a chair anymore? Please for the love of god do not spend any time or effort on this question.)

With highly dimensional characteristics (like chairness, or whether a given piece of music is country or not, or what it means for an entity to be considered “alive” or “conscious”), what typically happens is that there are not clear discriminators but rather ten or twenty or a hundred recognizable characteristics, and the presence of a critical number of them tips us over into saying yeah, that’s an instance.

Except it’s not just the presence of a critical number—sometimes some characteristics are more important than others. And some characteristics are anti-identifiers—things that our training data tell us shouldn’t be present, if it’s actually an instance—and if an anti-identifier is present alongside an identifier … what do?? Especially if there’s a lack of universal agreement about which characteristics matter in the first place. When you’re near the center of the cluster, things are pretty easy, but when things get hard, they can get really hard.

Which is why the first half my general prescription is to sidestep the question. Stop asking it. Stop caring about it. The second that the word/label/concept/category stops being useful in excess of its costs, and starts to become the center of attention in its own right, set it aside and proceed without it.

To select an example that has been oddly central in the culture wars of late: “Woman” is obviously a word that our ancestors invented for good reason. It’s a useful and valuable concept. It points at a genuine natural category out there in reality.

But there isn’t actually a clear boundary to that category. It’s not like copper atoms. Our “woman” recognizers look for countless little traits and features—

(like breasts and wide hips and long hair and soft skin and lower musculature and higher body fat and lighter body hair and no penis and two X chromosomes and a higher voice and a hormonal profile dominated by estrogen and makeup and dresses and earrings and jewelry and maybe still being paid less for the same work though it kind of depends on your baseline assumptions and on and on and on)

—and when those recognizers get 47 positives alongside 51 negatives, you could respond by feeling anxious and scrabbling for clarity—

—or you could pause and remember that “woman” is simply not a thing. Not in the way that each and every one of the individual monkeys out there, with all their confusing and fascinating variation, are. “Woman” is a conceptual bucket that we made up, to simplify a fuzzy and complex reality that does not care about whether we have a hard time processing it.

In other words: when you start debating What Really Makes A Woman A Woman (or Is J.K. Rowling A Transphobe) you’re not actually dealing with a question about the deep and fundamental nature of reality. You’ve been hoodwinked into a far more trivial game of which stickers we’re going to put on which objects and you can, in fact, just … recognize this for the distraction that it is.2

This is slightly stronger than Scott Alexander’s “just define the words in the way that lets you actually do good in the world.” It’s slightly stronger than Eliezer’s “replace the question about terminology with the question about characteristics, which is what you really care about.” It’s closest to Logan Strohl’s “this is probably just … not the question you should be asking.”

VIII. Syndrome Syndrome

Sometimes, babies just die, especially in the 1-4 month range. Sometimes, they die, and we can’t figure out what happened, and the parents are desperate for something to grab on to, something to make it all make sense, and sometimes they feel strangely better when the doctor says “it was SIDS.”

SIDS stands for “sudden infant death syndrome.” In essence, the parent is being told “your infant died of that thing where infants die sometimes.”

(There’s a little more detail in SIDS, but not much. This is really only a very slight caricature.)

And yet, this helps. Not for every parent. But for enough of them, it is a meaningful reassurance. There’s some part of some parents that relaxes, because the label “SIDS” exists, and now they Know What Happened (even though they really don’t).3

IX. Certainty Seeking

In Patient Observation, Logan Strohl writes:

When someone comes to me for advice on a long-standing adaptive challenge, the most common recommendation I give is, “Stop trying to solve this problem for a while. Start investigating the underlying territory instead.”

I recently chatted with someone who was worried that she might be a narcissist, and wanted to know what to do about it. She gave me permission to share these (anonymized) excerpts from our conversation.

Logan: my first thought is that this sounds like a situation where you'd do well to put "what should i do about it?" on hold for a good three months, and focus instead on "what is actually happening? how can i tell? what is it like? what is my brain doing by default in various situations, and which situations are the ones i care about here? which phenomena and mental motions seem important for understanding what's happening here?"

Crystal: That seems smart. But, seems better to know I am a narcissist than to be uncertain about it for three months... more comfortable I mean

Logan: i imagine that you have a question like "am i a narcissist?" in your head, and it's really salient because things you care about depend on the answer to it, and it's uncomfortable to not know the answer because you'd ideally orient to the two different worlds differently, and when you don't know which you're in you don’t' know how to orient. is that right?

Crystal: Yeah

Here, Crystal is demonstrating a need for closure. She is uncomfortable (understandably!) with being uncertain. She would like to make plans for the future. Those plans may be substantially different in worlds where she believes the answer to the question "am I a narcissist?" is "yes" than in the world where it's "no." She wants to know what to work on, in herself and in her relationships. She wants to know what to expect.

So when I recommend to her that she deliberately hang out in uncertainty while she gradually increases her contact with the territory, it feels bad to her.

Back to the conversation, jumping ahead a bit:

Logan: i tend to operate under the conjecture that when there is a thing that's been a problem for most of a person's life, that person's way of conceptualizing the problem is very likely to be incorrect or incomplete in ways that make investigation that's not driven by the concept more productive than investigation that is driven by the concept.

Crystal: The concept being “narcissism”?

Logan: yeah.

Crystal: How is it driven by the concept or not? What does that mean?

Logan: investigation that's driven by the concept looks like: how would i know if i'm a narcissist? what things are evidence for or against? where would i look for evidence of narcissism? what would disconfirming evidence look like? what are alternative hypotheses? how might i test them?

Crystal: That sounds like me

Logan: investigation that's not driven by the concept might look like: what does it feel like to be worried about whether i'm a narcissist? what seems to be at stake? if i go through the week and write down times when something related to the-thing-i-care-about-here happened, what do i end up writing? what was happening around me and in my head during those times? which of the things happening in my experience seems most closely tied to the-thing-i-care-about-here? how can i tell when that thing is happening in my head? if i watch for times when that thing is happening in my head and write down instances, what do i write?

Logan: in other words, it's possible to gain a lot of information about what's actually going on without having pre-decided most of what's going on. my suspicion is that this is a time when it makes sense to not pre-decide most of what's going on before you try to really seriously get in contact with the relevant region of territory

I often call the latter type of investigation—the kind that’s not driven by the concept—”exploratory investigation”. I’ve never used a word for the former type, but here I’m inclined to dub it “certainty seeking”.

Certainty seeking is often the right approach. It’s the right approach when you have good reason to think you mostly understand the situation and just need to fill in some details, or to determine the truth values of a couple central propositions. In that case, a more exploratory investigation style would be needlessly inefficient.

But people very often fall into certainty seeking when they are impatient. They already have a sketch, and for one reason or another, they just want to fill in the details and be done. They’re willing to shift a line here or there, but mainly they’re motivated to complete the drawing. “All I want to know is, is this narcissism or isn’t it? Yes or no?!”

A person in the grips of this impatient mode is not so much trying to learn the shape of reality, as to crystalize a satisfying concept so they can relax into certainty.

X. On autism and witchhunts

This is the last section of the essay. Before we get into it, I want to restate the problem as I see it, in brief.

(Again, the reason I didn’t lead with the concise statement is because the concise statement is a sazen and I genuinely think starting off with the sazen does more harm than good.)

The problem: People often treat conceptual handles (like “autistic” or “witchhunt”) as if they represent something real, such that there’s a real answer, out there in the territory, to questions like “am I really autistic?” or “is this a witchhunt?”

This habit (reflex?) comes with multiple downsides, among them:

People losing a lot of their connection to the observable phenomena around them and getting caught up in their predictions and preconceptions, the way that cops often really actually see a gun in the suspect’s hand even though the suspect was holding a phone and there were no gun-photons entering their retinas

People wasting a lot of time and energy fighting over semantics

I already talked about half of the solution above, which is “you can just not.” Part of the reason why this essay took its time and wandered so far afield was to give you lots of varied training data on the thing, so that you could develop a (dis)taste for it. You are, at this point, marginally less likely to unthinkingly default to the silly wasteful thing the next time an opportunity arises.

But there’s also an active and unusually good thing that you can do, having understood The Nature Of Labels™, and I want to take this last section to talk about how a non-confused, non-crazy person can mine them for value.

(There’s a principle in dog training that it’s much easier to swap behaviors than to stop behaviors; if your dog is chewing on your shoes, it’s easier to get it to chew on something else than to get it to give up chewing entirely.)

Here’s the recommended strategy:

When you start getting little pings in your X-recognizer—

(e.g. you begin to suspect that maybe there’s a witchhunt afoot, or you begin to wonder if perhaps you are autistic)

—instead of completing the analysis, and seeking a final and definitive answer about whether this is a Real X Or Not,

just go ahead and use the existence of a pre-collected and pre-organized corpus of data on X to make headway on whatever it is you actually care about. Let X narrow your search and focus your attention, and don’t require that X justify its usefulness by passing a bunch of arbitrary tests.

If it’s maybe a witchhunt and maybe not—well, now that the term “witchhunt” has occurred to you, you can start looking for what people do to stop or ameliorate witchhunts. You can skip the middleman, so to speak, and just do the things that are good in this situation regardless of whether it’s “actually” a witchhunt.

If you’re maybe autistic and maybe not—well, something promoted the question to your attention in the first place. Are you struggling with your interpersonal relationships? Having a hard time with sensory sensitivity? Unsure whether it’s healthy to pursue a special interest on Into the Night, week in and week out?

Great—go look for tweets and subreddits associated with the hashtag #actuallyautistic and just … see what the autists have figured out. You don’t have to be autistic to benefit from the research and experimentation of people with autism.

I’m exaggerating a little, here. I don’t actually recommend that you try to force some sort of fake incuriosity about whether you would in fact qualify for a diagnosis. If you’re curious, you’re curious, and there is real value to be had in gaining clarity.

(For instance, taking a bunch of online autism assessments could open your eyes to areas that you might not have even known were associated with autism, and where you might not have been actively struggling but could nevertheless benefit from intervention anyway.)

The point is to treat (e.g.) figuring out whether the present situation in your workplace meets the literal definition of “witchhunt” as a means to an end, and not as an end in and of itself. To be wary of getting caught up in the game of wordplay for its own sake, to the detriment of your real goals. If you make a Compelling Argument that your colleagues are engaged in a witchhunt, via researching and referencing other instances of witchhunts and the general dynamics of witchhunts, you will have clarified your thinking and focused your investigations on the interesting and relevant parts of reality, and that’s all to the good.

But once you’ve done that—once you’ve clarified your thinking and focused your investigations—at that point, the question of which word means precisely what things should hopefully seem pretty uninteresting, actually. The value of having the words be precise and unambiguous is so that they can guide you through the territory. Once you know the trail by heart, the exact lines on the map shouldn’t feel like they matter all that much.

(To you, in your current situation. If you want to make a better map, for the next person to come along, that’s also good and noble.)

A whole other way to say all of this is that you can replace questions like “is this a witchhunt?” with questions like “if I run with the tentative hypothesis that what I’m seeing is a witchhunt, what does that buy me? What resources does that make me think of accessing, and what subquestions does that make me want to investigate, and what next actions does that hypothesis suggest?”

(There’s also “and if I’m wrong, and it’s not what it looks like, and I’m being fooled by a mere surface resemblance, then what’s the next most likely explanation for what I’m seeing, and how would I come to discover that that’s what’s actually going on?”)

In short, you can treat the conceptual handle as a muse. A lens to look through, a light to guide you, a source of inspiration and a way to sort the wheat from the chaff.

And it can be all of that without you precisely pinning down every last inch of its borders. In many cases, the effort to pin down every last inch of its borders comes at the expense of what actually matters.

“Hey, instead of fighting over whether X means that this is ‘abuse’ or not, can we maybe just, y’know, solve X? I mean, even if we decide it’s just barely not ‘abuse’ in a technical sense, it still, uh, sucks, right? Like if it’s so hard to tell that we’re fighting over it, then it’s got to be near enough to abuse that it’s worth changing, no? And since it sounds like nobody’s planning to go to court over this, I don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish by litigating the terminology.”

… that seems a little bit less like losing the thread, to me.

“Crisis” is a word that very easily could have been on our first list.

There is a very different thing, which is recognizing that which stickers we put on which objects informs and influences some other very real games, like war and bigotry and politics and so forth. The thing I’m saying here is not “there’s NEVER a reason to care about the stickers.” It’s “don’t lose track of the plot and get all caught up in caring about the stickers if there ISN’T an external, compelling reason to do so.” I think it’s entirely reasonable to fight over definitions of race or gender or religion because those definitions carry power within our society, and the specifics of how we draw the lines will change the shape of the future. But I think it’s very very easy for people to lose track of the “because,” and get caught up in this sort of hand-wringing without an endorsed reason, and to reach for “but this matters because of the culture war” as a post-hoc justification when really something else was going on under the hood.

Another piece of this puzzle is that parents often feel guilt, and want to know whether it’s their fault/whether they should have done something differently, and a diagnosis of SIDS tells them “no, it’s not your fault, you didn’t do anything wrong.” This is a different vein of reassurance than the mere wanting-to-know, so it’s worth noting separately.

This is useful, thanks

Nirvana is often translated as either "emptiness" or "freedom". Specifically, emptiness or freedom of *concepts*. I am pretty sure that in a previous life, Duncan was a Zen master.