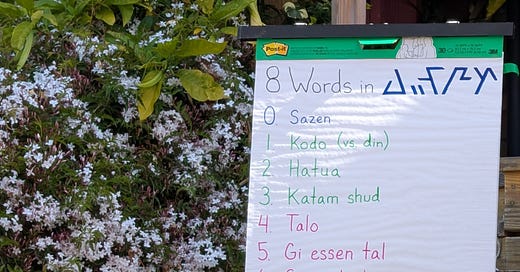

I recently gave a talk at DunCon titled “Eight Words in Agori.” My thinking was that, if I could highlight a handful of places where Agor wanted there to be a word, where English doesn’t already have a word, this would be a good way to point at the differences between the culture of Agor and the culture of e.g. the rationalist enclaves of California.

(Both Japan and America have sunlight filtering through the leaves of the trees, creating beautiful dappled patterns of light and shade. But Americans don’t have the word komorebi. I’m not full-blown Sapir-Whorfpilled, but I do notice that Japanese animation à la Miyazaki prominently features komorebi and American animation almost entirely lacks it, and this feels like an important hint about how language and culture influence each other.)

I generally agree there should be a pretty high bar for pushing new jargon, so I’m not currently intending to share all eight of the Agori concepts I talked about at DunCon. But the one (pair) that seemed most useful to the attendees feels worth writing about, similar to how I previously swallowed my embarrassment and wrote up the Agori concept of sazen.

Kodo (lit. “that which cuts”)

You’ve bought a new outfit, and you’re not sure whether it looks good or not; both “my new outfit looks good” and “my new outfit does not look good” seem like possible worlds and you don’t know which world you’re actually in.

A journalist critical of the Russian government has died under suspicious circumstances; it seems likely that they were poisoned, though it also seems possible that this was just an unfortunate random coincidence.

You’d really like to know whether things like autism and gender dysphoria are actually on the rise, or whether their apparent rise is just due to increased awareness and diagnosis.

You’d really like to know whether there’s an afterlife.

A kodo is a thing which tells you which world you are in. It’s something that behaves differently, depending on which world you’re in. It cleaves the two possibilities apart from one another.

If you ask your friend whether the new outfit looks nice, they might be the sort of person who gives blunt, honest, and well-calibrated feedback. But they might be the sort of person who just says Nice Things, to be nice. Their opinion is a kodo in the former case, but not the latter.

If you ask the Russian government whether they assassinated the journalist, their answer of “no, of course not” is not a kodo. They would deny it either way. The fact of their denial gives you no new information whatsoever, unlike (say) an autopsy and some security camera footage.

(It’s sort of like in the riddle of the Two Guards, one of whom always tells the truth and the other of whom always lies. There are some questions, such as “are you telling the truth?” that are useless in this situation. The truth-telling guard will (honestly) answer “yes!” and the lying guard will (deceptively) answer “yes!” Hearing a guard explicitly claim to be telling the truth simply does no good.)

Din (lit. “it says nothing”)

The opposite of kodo is din.

(I give you permission to write it as “dyn” if you want to go out of your way to make it clear that you’re not using the English word for “noise,” but the cognate is a feature, not a bug. Din is the noise to kodo’s signal.)

Something is din if you would expect to observe it in all cases—the Russians denying the alleged assassination, the guards claiming to be honest, your gentle friend assuring you that your outfit is fire. Because you would see it no matter what, it doesn’t help you when it comes to figuring out which world you’re actually in.

Imagine, for instance, that the afterlife is real, and that this information was somehow conveyed to our ancestors in the ancient past. Then you would expect people to tell you that the afterlife is real. You would expect them to offer it up as reassurance to children afraid of death, and as a comfort to those grieving at funerals. You would expect people to treat the knowledge with reverence, to pass it on from generation to generation with evocative stories and memorable details.

But! Imagine for a moment that the afterlife is not real. In this world, what would you expect to see?

Because death is frightening, and because people tend to flinch away from fear and seek comfort, and because people make up all sorts of stories all the time, and because people don’t often care all that much whether something is true or not so long as it makes them feel better, and because people tend to believe things if enough of their friends and family and respected elders all say it…

…I would expect to see the same sorts of claims, about the afterlife, in a world where it doesn’t exist. I would genuinely expect people to invent the afterlife, and the thing that I would expect them to invent looks a lot like what they would say if it were true, actually, and therefore hearing the-sorts-of-things-people-typically-have-to-say about the afterlife doesn’t tell me anything at all. It’s din.

(Rule of thumb: be prepared to encounter din wherever people would benefit from the appearance of X, regardless of whether X is true or false.

e.g. performative outrage tends to garner support and status whether the-thing-they’re-outraged-about is actually a big deal or not; the existence of performative outrage doesn’t tell you whether it is.

e.g. if your romantic partner is considering leaving you but hasn’t actually decided to yet, then there’s a good chance they’re going to decide to say soothing, reassuring things to you. And if your romantic partner is not considering leaving you, and you’re just caught in an anxiety spiral, then there’s a good chance they’re going to decide to say soothing, reassuring things to you! There are some partners out there whose reassurances are not din, but there are a lot of people whose reassurances would be.)

Isn’t this just…?

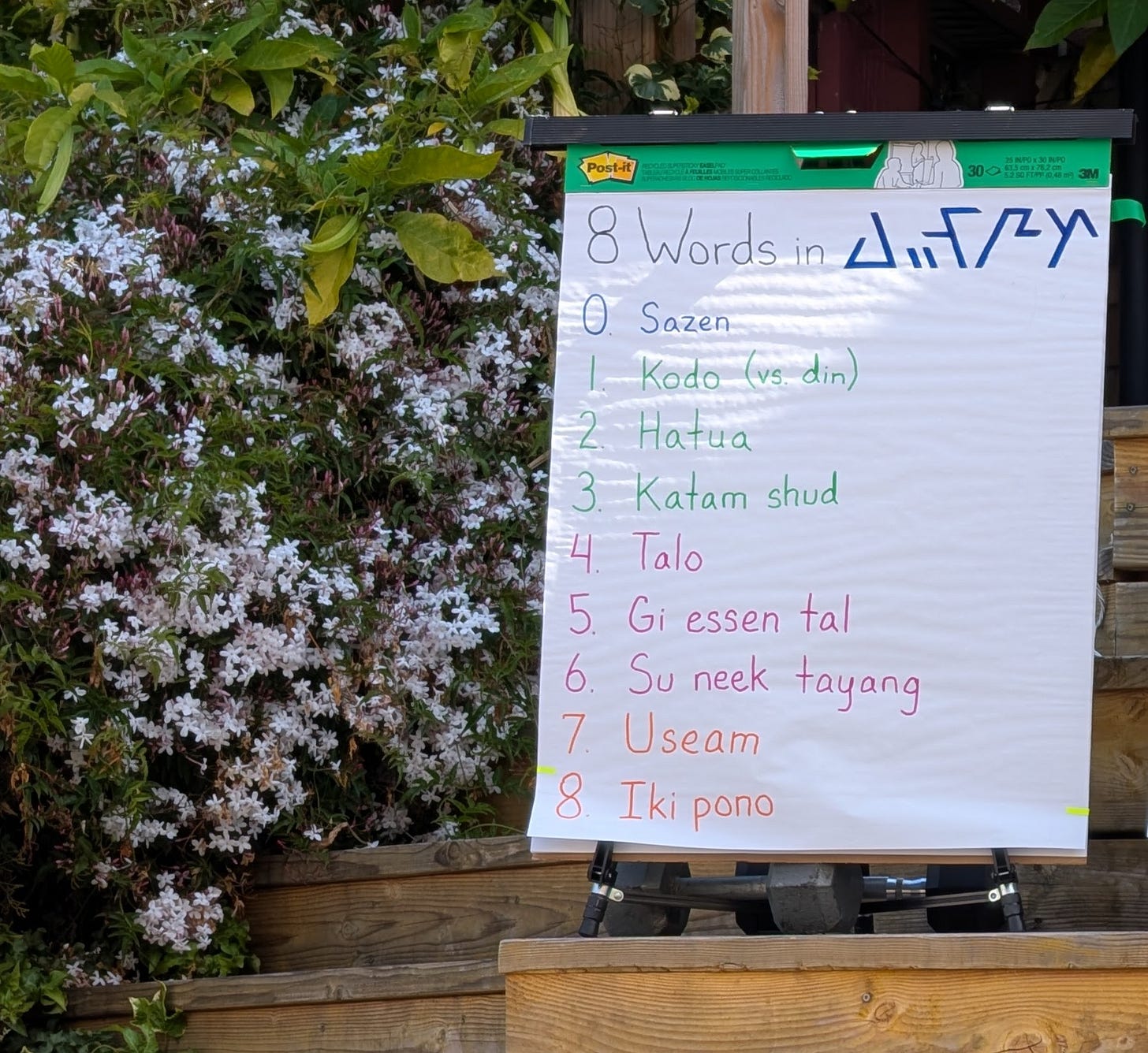

Yes. This is just the scientific method, in which you look for some kind of observable that behaves differently depending on whether the hypothesis is true or false. Yes, this is just information theory 101, in which making an observation of X tells you something about Y if and only if the possible values of X have different probabilities given different states of Y. Yes, this is just the concept of a “discriminator,” or “strong Bayesian evidence.”

(Yes, this is just the final step of split and commit, in which, having thought about what would be an appropriate action in World A, and what would be an appropriate action in World ¬A, you set about trying to figure out which world you’re in so that you know which action to actually take.)

But concepts like “discriminator” or “strong Bayesian evidence” are not lay concepts, in English. They’re the sorts of things that a certain kind of college graduate may take in stride, but they are not generally accessible.

Kodo and din, on the other hand, are kindergarten words. In the imaginary culture of Agor, they’re baked in, taught and exemplified and practiced from early childhood—

“Wait, wait—hang on, Finley—remember what we said? A big apology right here in front of everybody isn’t quiiiiite the thing we’re looking for. If you do this right now, Elliot won’t be able to tell if you really mean it, or if you were just doing it because everyone was watching. Why don’t you go over to the reading corner and think for a little bit about what you actually want to say, okay? And then you can talk to Elliot after lunch, if you both want.”

—and this has profound and pervasive effects.

(Importantly, it’s not just about the concepts themselves seeing regular use. It’s also about living in the sort of culture that would invent the words, that sees from a perspective in which of course these things should be taught early and taken seriously, of course we need short words so that we can refer to them quickly, of course we want to be able to take them for granted, treat them as universal background knowledge that can be leaned upon without explanation or elaboration.)

It’s a little bit like what happens when [basic economic literacy] or [the principles of operant conditioning] reach a tipping point, within a subculture. When enough people understand how incentives and reinforcement work, lots of things change. Teaching and parenting start to look a lot less authoritarian, and a lot more like a combination of training and employment. Engineering shifts (e.g. fewer big signs directly telling people what they’re supposed to do and more intentional design that makes easy and intrinsically rewards the desired behavior). A culture that thinks in terms of incentives and disincentives and paths-of-least-resistance starts to have a lot less in the way of friction and papercuts and wasted motion.

Similarly, a culture that has prioritized teaching its children to understand the difference between kodo and din—

(And given them practice in seeking out kodo, and encouraged them to disregard din)

—has a lot less of a fairly common (in this culture) kind of confusion.

e.g. the kind of confusion that leads media outlets to feel obligated to repeat what the Trump administration claims is true about such-and-such problem or such-and-such initiative, even though the Trump administration has demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that its spokespeople will emit exactly the same sentences regardless of whether that problem is actually real or that initiative is actually working.

e.g. the kind of confusion that leads people to believe that they generally understand the psychology and behavior of psychopaths and pedophiles, because they happen to know things about the psychology and behavior of the tiny fraction of psychopaths and pedophiles who both a) go on to become serial killers and child molesters, and b) also get caught.

(The entire essay Social Dark Matter was written from an Agori perspective and its thesis is basically “most of your observations on these topics are inescapably din; most of you are not even trying to find an actual kodo.”)

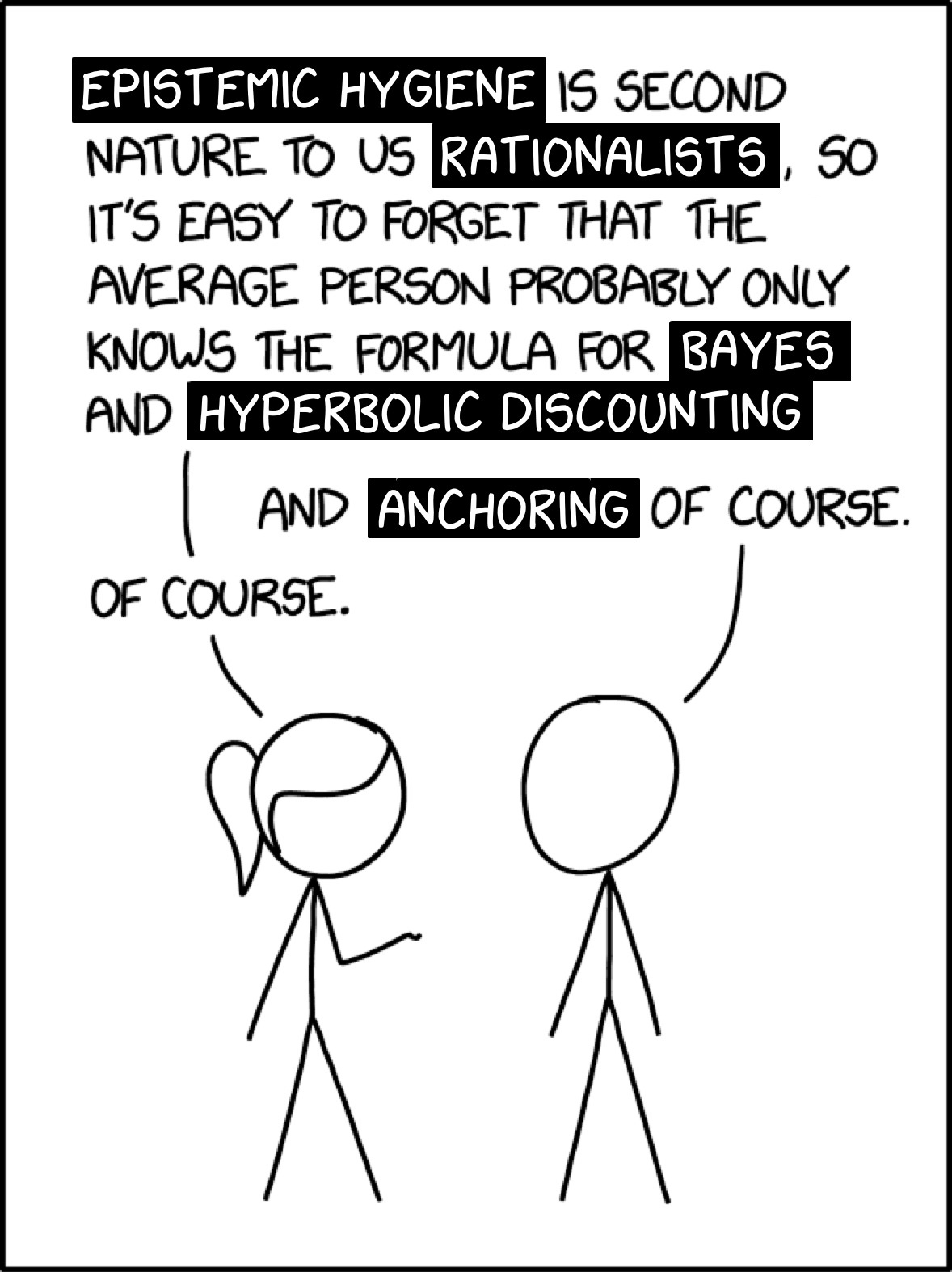

e.g. the kind of confusion that leads to dynamics like this:

Growing up with kodo and din in the water supply leaves people more likely to notice that they would be criticized in every single branch, and that therefore the criticism isn’t actually a response to their actions and isn’t especially valid or worth attending to.

(And in a culture where everybody has this sort of grounding, it’s much easier to coordinate effectively to ignore and deplatform sources of commentary which basically only produce din. From the inside of America, it sometimes feels like the problem of alt right media is inevitable and cannot be fixed, but just as many nations do not have a school shooting epidemic, so too do many nations not have a din epidemic. Human culture is not infinitely flexible; there are some things that consensus and education can’t train out of us, or train into us. But there are many things that consensus and education can influence, as evidenced by how wildly different the cultures of Japan, Namibia, Cambodia, and Estonia are.)

Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi

I’ve drifted away from simply explaining what kodo and din are to a bit of a pitch for why the world is better if more people care. That’s because I think the world is better if more people care, and I’d genuinely like for you to start thinking in terms of kodo and din. Not necessarily by their weird, made-up names, but in principle and in practice.

To build the habit of asking yourself, in every case, “wait—but how would I actually know? What sorts of things are detectably different in these two different possible worlds?” until it no longer requires effort and is just … how your mind works.

To in fact learn to tune out, disregard, and the-opposite-of-encourage-or-incentivize people who are spouting din, or paying attention to din. To resist the temptation to fight back and engage with din, as if it will play by the rules and go away once you’ve proven it wrong.

(Remember, by definition, din is something they would have said regardless of the state of the world, so proving that the state of the world is one way and not the other isn’t going to change anything.)

Of the two, I suspect the latter is probably more important? Developing an appropriate distaste for contentless noise feels more like what the average American needs to do, and if you reliably walk away from din you eventually end up at kodo anyway. The problem seems to me to be less about bits of truth being downplayed, and more about vast quantities of anti-truth being up-played. Worthless bullshit is being legitimized, platformed, and taken seriously/argued against at length, when it should in fact be laughed out of the room or just outright ignored. Brandolini’s Law comes to mind, as does the adage “don’t feed the trolls.”

In the end, this feels like an awful lot of words to spend on what feel like some very basic and straightforward points—

Some stuff conveys information and other stuff doesn’t

The stuff that conveys information is good and useful; you should practice the skill of locating it (which starts with forming an intention to try at all)

You should actively guard against the other stuff; being consciously aware that it’s bullshit helps a lot but that’s not as good as actually getting it the heck away from you

—but then again, I’m a boy from Agor. A boy from Japan might be confused at how little we attend to the patterns of light and shadow caused by the sunlight filtering through the leaves; just because something feels basic once you already know it doesn’t mean that it’s easy to crystallize in the first place (especially if you have to do so all on your own). The distinction between kodo and din is clearly not being taught to enough people ‘round these parts, or we would have a very different set of problems.

Well written as usual!

To give one more example, here's a situation I recently encountered where I really would have liked "kodo" and "din" be in the shared conceptual vocabulary.

---

As school ends for the summer vacation in Finland, people typically sing a particular song ("suvivirsi" ~ "summer psalm"). The song is religious, which makes many people oppose the practice, but it's also a nostalgic tradition, which makes many people support the practice. And so, as one might expect, it's discussed every once in a while in e.g. mainstream newspapers with no end in sight.

As another opinion piece came out recently, a friend talked to me about it. He said something along the lines: "The people who write opinion pieces against the summer psalm are adults, every time. Children see it differently". And what I interpreted was the subtext there was "You don't hear about children being against the summer psalm - it's *always* the adults. Weird, huh?"

I thought this was obviously invalid: surely one shouldn't expect the opinion pieces to be written by children!

(I didn't say this out loud, though. I was pretty frustrated by what I thought was bizarre argumentation, but couldn't articulate my position in a snappy one-liner in the heat of the moment. So I instead resorted to the snappier - but still true - argument "when I was a kid I found singing the summer psalm uncomfortable".)

If the two different worlds are "adults dislike the summer psalm, but children don't mind it" and "both adults and children dislike the summer psalm", then you'd expect the opinion pieces to be written by adults in either case. It's not kodo, it's din.