Thresholding

Or, "the 2.9 problem"

If I were in some group or subculture and I wanted to do as much damage as possible, I wouldn’t create some singular, massive disaster.

Instead, I would launch a threshold attack.

I would do something objectionable, but technically defensible, such that I wouldn’t be called out for it (and would win or be exonerated if I were called out for it). Then, after the hubbub had died down, I would do it again. Then maybe I would try something that’s straightforwardly shitty, but in a low-grade, not-worth-the-effort-it-would-take-to-complain-about-it sort of way. Then I’d give it a couple of weeks to let the memory fade, and come back with something that is across the line, but where I could convincingly argue ignorance, or that I had been provoked, or that I honestly thought it was fine because look, that person did the exact same thing and no one objected to them, what gives?

Maybe there’d be a time where I did something that was clearly objectionable, but pretty small, actually—the sort of thing that would be the equivalent of a five-minute time-out, if it happened in kindergarten—and then I would fight tooth-and-nail for weeks, exhausting every avenue of appeal, dragging every single person around me into the debate, forcing people to pick sides, forcing people to explain and clarify and specify every aspect of their position down to the tiniest detail, inflating the cost of enforcement beyond all reason.

Then I’d behave for a while, and only after things had been smooth for months would I make some other minor dick move, and when someone else snapped and said “all right, that’s it, that’s the last straw—let’s get rid of this guy,” I’d object that hey, what the fuck, you guys keep trying to blame me for all sorts of shit and I’ve been exonerated basically every time, sure there was that one time where it really was my fault but I apologized for that one, are you really going to try to play like I am some constant troublemaker just because I slipped up once?

And if I won that fight, then the next time I was going to push it, maybe I’d start out by being like “btw don’t forget, some of the shittier people around here try to scapegoat me; don’t be surprised if they start getting super unreasonable because of what I’m about to say/do.”

And each time, I’d be sure to target different people, and some people I would never target at all, so that there would be maximum confusion between different people’s very different experiences of me, and it would be maximally difficult to form clear common knowledge of what was going on. And the end result would be a string of low-grade erosive acts that, in the aggregate, are far, far, far more damaging than if I’d caused one single terrible incident.

This is thresholding, and it’s a class of behavior that most rule systems (both formal and informal) are really ill-equipped to handle. I’d like for this essay to help you better recognize thresholding when it’s happening, and give you the tools to communicate what you’re seeing to others, such that you can actually succeed at coordinating against it.

I.

There are at least three major kinds of damage done by this sort of pattern. The first is the straightforward badness of the behaviors themselves—a hard punch on the arm may be nowhere near as unpleasant as someone breaking your nose, but if you get punched on the arm over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over, it adds up.

A lot of people would rather have two consecutive 3-out-of-10 bad experiences than one lone 6-out-of-10 bad one, because two 3s add up to something somewhat less than one 6. But a dozen 3s-out-of-10 are almost certainly much, much worse than a single 6, in terms of the overall hit to one’s quality of life. People certainly regret the romantic partners who hurt them acutely, but the really awful traumatic stories are the ones where the thousand cuts stretch on for years and years. Someone who manages to stick around and keep on doing harm often does far more damage than someone who is more memorably and explosively bad.

The second kind of damage is institutional. Thresholding exploits a sort of loophole or blind spot in the way we build rule systems (more on this in the next section), with one result being that people lose faith in those systems—

—and understandably so! If the whole purpose of the system is to prevent harm and enact justice, but harm is happening anyway and justice is nowhere to be found, why wouldn’t you start to question whether this system is worth supporting?

But there’s a difference between counting down from perfect, and noticing that the system is flawed and fails in certain cases, and counting up from zero, and noticing all of the ways in which the system is better than nothing. Thresholding can cause people to focus too hard on the frustrating, visible, repeated failings of the system, which can lead people to give up on the system prematurely, which can result in a much worse world for everyone involved.

The third kind of damage is interpersonal. Thresholding drives people apart. For the people who have been victimized, or who see and understand the pattern, there’s a clear and obvious problem with a simple solution—get rid of that guy! Or at least bring the hammer down on him, come on, are you serious, how are we not dealing with this?

But a clever thresholder spreads the badness around, appearing quite innocent before some people, and convincingly contrite/apologetic before others. A clever thresholder will have an established record of vindication to point to, for all the previous times they were accused and found innocent (or at least not punishably guilty) and will be able to convince at least some people that they’re being unfairly persecuted.

And so individuals who were nowhere near the original badness themselves will find themselves on opposite sides of a charged disagreement, with wildly different takes on the ground reality of the situation.

(e.g. Donald Trump was convicted of crimes because he committed crimes, versus the whole thing was based on trumped-up charges from a politicized institution in the first place (although admittedly with Trump there are other things going on, too, like disagreements over whether his targets deserve protection in the first place).)

Like I said: definitely more effective, if I really want to kill a subculture from the inside, than just showing up and giving everybody one or two really bad days.

II.

Rules and laws, in the sense of formal, explicit systems, are largely an attempt to model and clarify (and, importantly, simplify) what people were already doing.

People knew it was bad to kill people—

(at least, other members of your ingroup who were in good standing 🙄)

—long before Hammurabi. People were responding to other people killing each other long before Hammurabi. What Hammurabi did was sort of analogous to what grammarians do: he looked at the evolved responses to various acts, and tried to describe them and codify them. The Code of Hammurabi was an overlay, a set of crisp comic lines drawn over top of the more complicated, preexisting reality.

“We all pretty much know what ‘fair’ is, but here, I’ll spell it out just so there are no misunderstandings. If you get drunk on wine and get in a fight with your ex’s new squeeze and in the tussle his eye gets poked out, then your eye is going to get poked out, too. If you don’t like it, make sure you don’t poke his eye out in the first place.”

Sure, there was probably some degree of imposition, in that Hammurabi was probably trying to put a stop to various scurrilous excesses and get the most aggressive people to pull back a bit. But the median Babylonian was most likely not actually being asked to change their behavior. The code of Hammurabi was a formalization of principles that were probably already largely in play throughout much of the kingdom.

Today, we often formalize rules and regulations to cover novel ground—our legal system is sort of desperately scrambling to keep up with swiftly shifting social mores and whole new swathes of possibility opened up by technology and globalism. Even so, though, when we write new laws to try to cover new territory, we’re still usually relying on some preexisting sense of how-things-go and what-would-be-good. People ask questions like “is it fair for the developers of AI art programs to get to piggyback off of the expertise of unpaid artists?” and then try to hammer out structures and systems that will shore up the places where the incentives aren’t quite right.

But—as is almost always the case—the superimposed, after-the-fact structure isn’t a perfect match for reality.

Laws—

(and codes, and principles, et cetera)

—like maps, have the benefit of being (relatively) streamlined and simple. They (supposedly) break things down into clearly defined buckets and categories. They’re (meant to be) straightforward and unambiguous in a way that reality often isn’t. There are uncountably myriad awful things that one human being can do to another with a raw potato, but if they do something that meets the criteria for “aggravated assault,” then we know how to respond even if the specific atrocity is one we’ve never seen before. We don’t have to account for every possible little variation; we don’t have to make up a brand-new response for every different act. We can cluster things—abstract away all the messy detail and focus on the crux of the issue…

…ideally, anyway. The very fact that this isn’t actually how it works is precisely why lawyers make so much money. You can define a category like “aggravated assault” and list its defining characteristics, but reality isn’t that simple or straightforward, and there will always be ambiguity, at the edges, about which things fall inside the bucket versus outside of it.

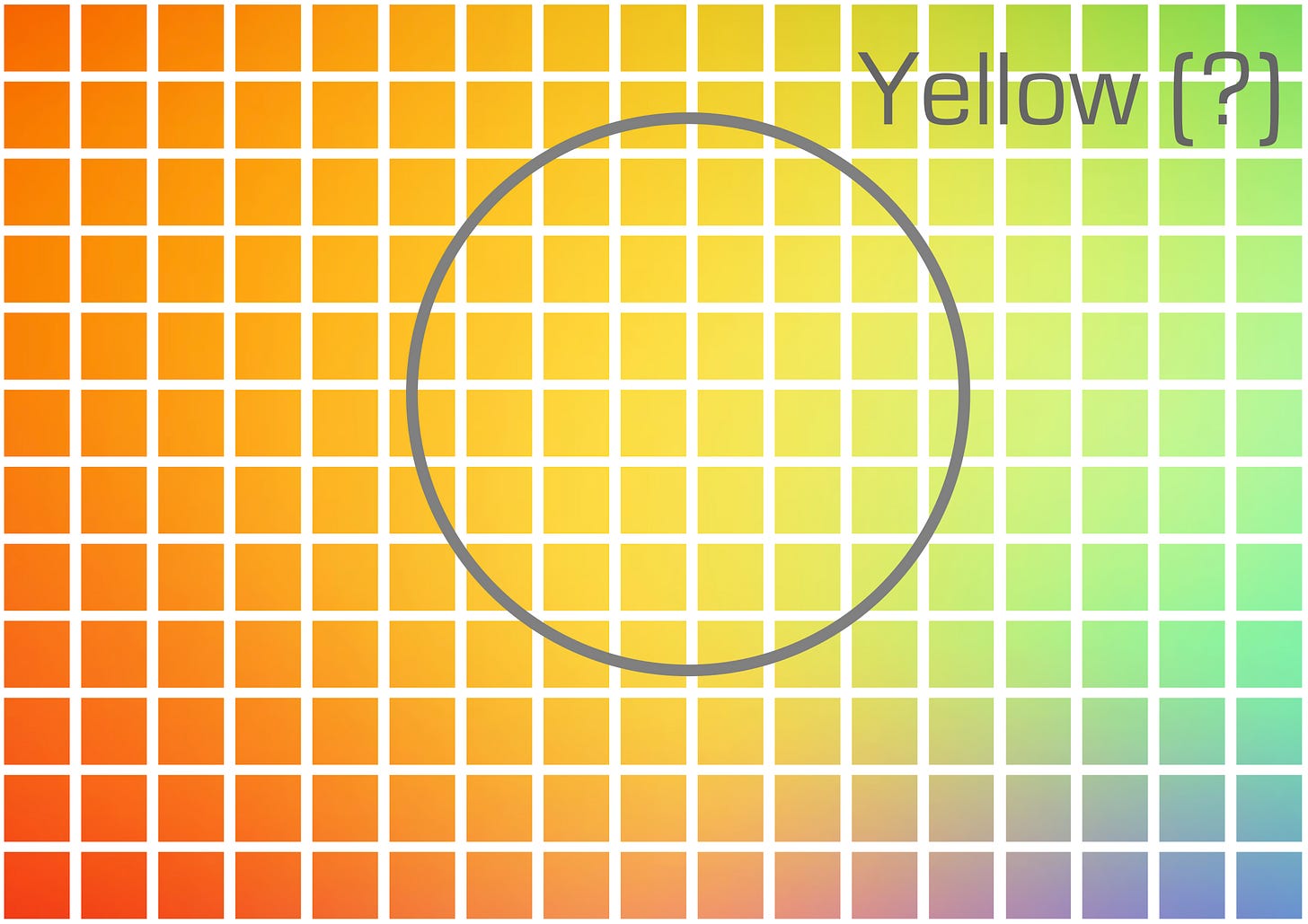

That’s because there isn’t actually a bucket, out there in the territory, and so our attempt to pretend that there is is like…

Hm. This is a little bit clumsy, as a metaphor, but imagine a world made of large, toddlerish pixels, and a bucket that’s defined to be a perfect circle:

…sure, the things near the center of the bucket are yellow—

(or are they more golden?)

—but there’s stuff near the edges that could go either way, and there just isn’t actually a clear distinction between yellow and not-yellow the way the bucket wants us to pretend.

The matchup between [the framework of rules and laws] and [reality] is like that, except they’re not just pixels, they’re multi-dimensional n-voxels that are wriggling around at random and sometimes changing position—

—and also there’s wind that’s blowing them around so they’re not falling straight down into the bucket, sometimes they’re being scattered in unpredictable directions and other times there’s a consistent wind so that some stuff that belongs in the bucket systematically ends up outside of it and ugh, it’s all a mess.

All of which is to say: behavior X and behavior Y might be very similar, almost indistinguishable, and yet because legal systems have thresholds, X might fall on one side of the line and result in jail time while Y falls on the other and gets probation, and that’s true even if the system is working properly. It’s an inescapable side-effect of trying to impose crisp boundaries on a reality that is fuzzy and messy—even the best, most well-intentioned, most carefully applied legal framework will still result in arbitrary-feeling distinctions, at the boundaries.

(And things get even worse when standards are imperfectly and inconsistently applied, e.g. to favor some demographics while penalizing others, which happens approximately always.)

III.

When I say “the line,” above, I’m mostly talking about whether [the people who are in a position to respond to a given behavior] choose to do so, or not.

Response is expensive. It takes time, attention, and resources that often feel like they could be better spent elsewhere, especially since the recipient of the response is frequently not particularly receptive or cooperative.

(Imagine what it would take to secure justice from someone who’d hurt you on the order of stealing five dollars of value from you. Under most circumstances, it would cost you a lot more than five dollars to try to get that money back, or to try to get the person punished, or whatever.)

It can also be socially expensive. Other people, looking in from the outside, won’t necessarily understand or agree that you have, in fact, been wronged (or that you are, in fact, attempting to mete out impersonal justice, if you’re not the victim yourself). Unless the violation that occurred was clear and explicit and there are preexisting, unambiguous rules about it, it’s pretty easy to be pigeonholed as vindictive, unfair, “making too big a deal out of it,” fascistic, etc.

(This is a major part of why people are motivated to create crisp, legible rules in the first place—so that when transgressions do occur, registering a complaint is seen as not-your-fault rather than as being petty or cruel or what-have-you.)

Other factors that are often in play:

Uncertainty about the magnitude of the badness, and therefore the magnitude of an appropriate response

Uncertainty about what actually happened, and whether or not it meets the criteria for whatever rule is allegedly relevant

Uncertainty over whether the guilty party has actually been identified; how likely it seems that the accused actually did the thing

Uncertainty over motive and intent, and whether the alleged culprit was being knowingly bad or should be treated as unfortunately oblivious or otherwise unlucky

Uncertainty over extenuating or ameliorating circumstances, i.e. even if we’re sure they did it and even if we’re sure it’s bad, were they provoked? Did the other side do it first? Was their judgment impaired in some way that wasn’t their fault, or which we have sympathy for?

Unfairness within the system itself (e.g. punishments that are too harsh relative to the transgressions they’re punishing, or bias against various groups such that they receive punishment for transgressions that others don’t)

The importance of the people involved in various social or political dynamics; whether there are pressures toward or away from punishment in general

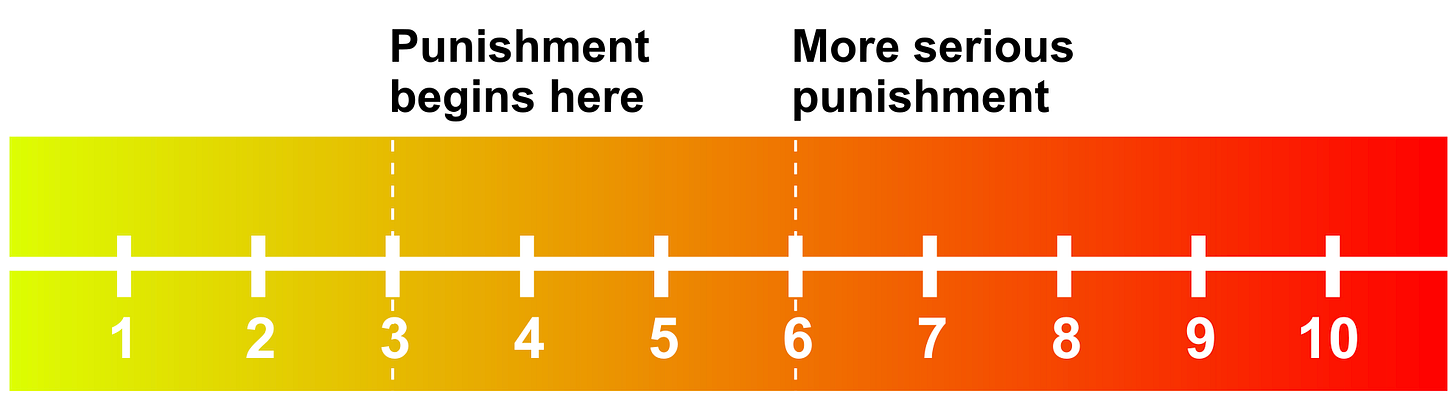

…all of these things (and more that I haven’t listed) come together in a complicated and often implicit calculation that cashes out to a gestalt sense of “how bad” a given behavior was. Something that’s a 4 on some arbitrary linear scale might end up being treated like a 3 because of various uncertainties, or like a 5 because they’ve been caught doing 4s before and (apparently) need to be taught a lesson.

But ultimately there’s still (usually) a binary sort of are-we-doing-this-or-not quality to the overall decision. Are we citing them, or letting them off with a warning? Are we filing a formal complaint, or not? Will there be a fine, or jail time, or neither?

And so there’s still something like a linear scale with thresholds for various responses, even though there might be dozens of factors going into the calculation of how-bad-it-was-on-a-scale-of-one-to-ten.

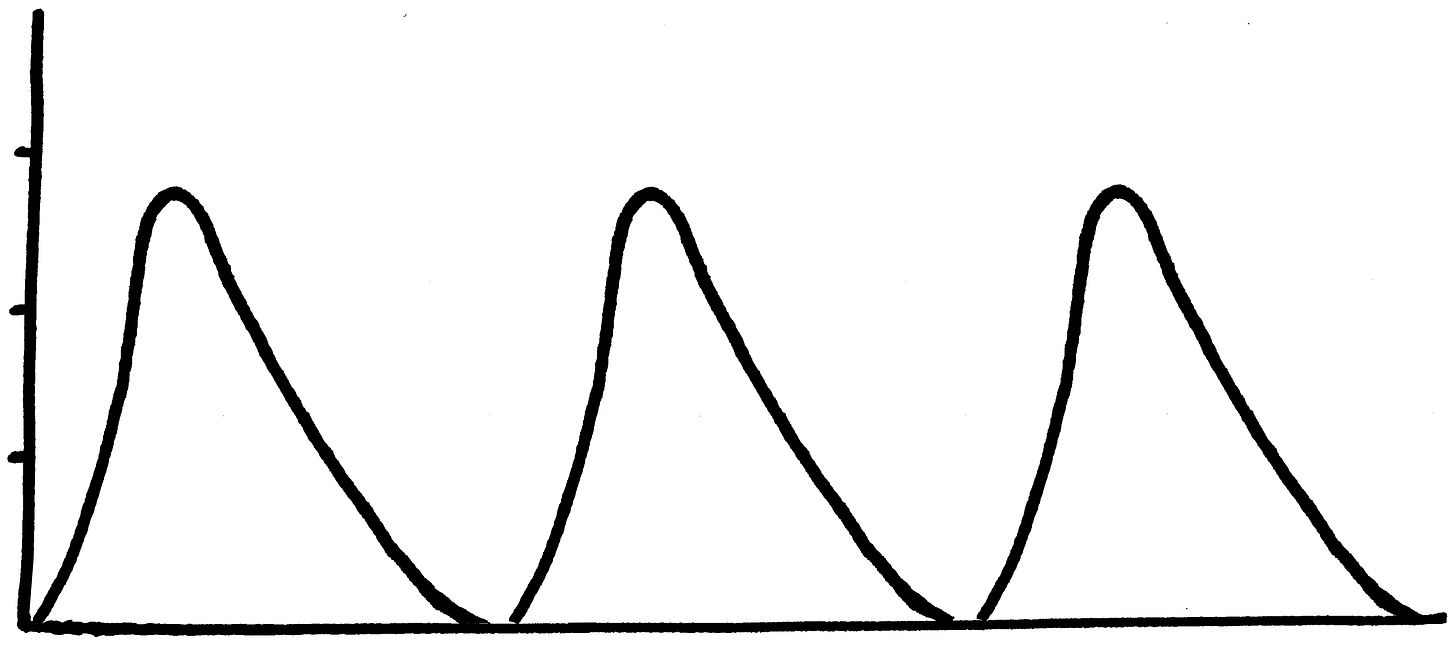

…and what happens, in a situation like this one, is that there’s a strong incentive to pull 2.9s (and to a lesser extent 5.9s). 2.9 is an attractor, in the sense that it’s the best purchase for a rulebreaker—you get the most of whatever-it-is you were getting out of breaking rules, without actually having to pay for it.

IV.

The problem isn’t when somebody pulls a 2.9. That does kind of suck, for the system as a whole, but eh—if it’s true that a 2.9 is not really worth the time and energy to hunt down and consequent—

(i.e. if the line was in fact drawn in basically the right place, as opposed to maybe underweighting the badness of a given sort of misbehavior)

—then people occasionally getting away with 2.9s is sort of the standard cost of doing business. Like “breakage” or “shrinkage” in retail—you sort of expect that you’ll take some damage below the level of what calls for a response.

The real problem arises when someone begins 2.9ing on the regular—either deliberately or unconsciously exploiting the lack-of-response on one side of the line.

Most people are already not very good at tracking behavior across time; most people have a hard time remembering the details of various interactions and largely allow their overall feelings to a) color what they do remember, and b) fill in the cracks.

This “problem”—

(I’m putting the word problem in scare quotes because it’s not actually clear to me that it is a problem, overall; it could be that the standard amount of mild amnesia is actually a good thing most of the time)

—is only exacerbated once there’s some sort of system for tracking and taking care of misbehavior. As soon as there’s an authority that is willing to write down everyone’s misdemeanors and felonies, everyone else breathes a sigh of relief and starts doing “background checks” that just look for a Y/N on “is this person a criminal?” People (in general) outsource their record-keeping to the authority, once it exists. They rely upon it, to track what would be expensive for them to track, themselves.

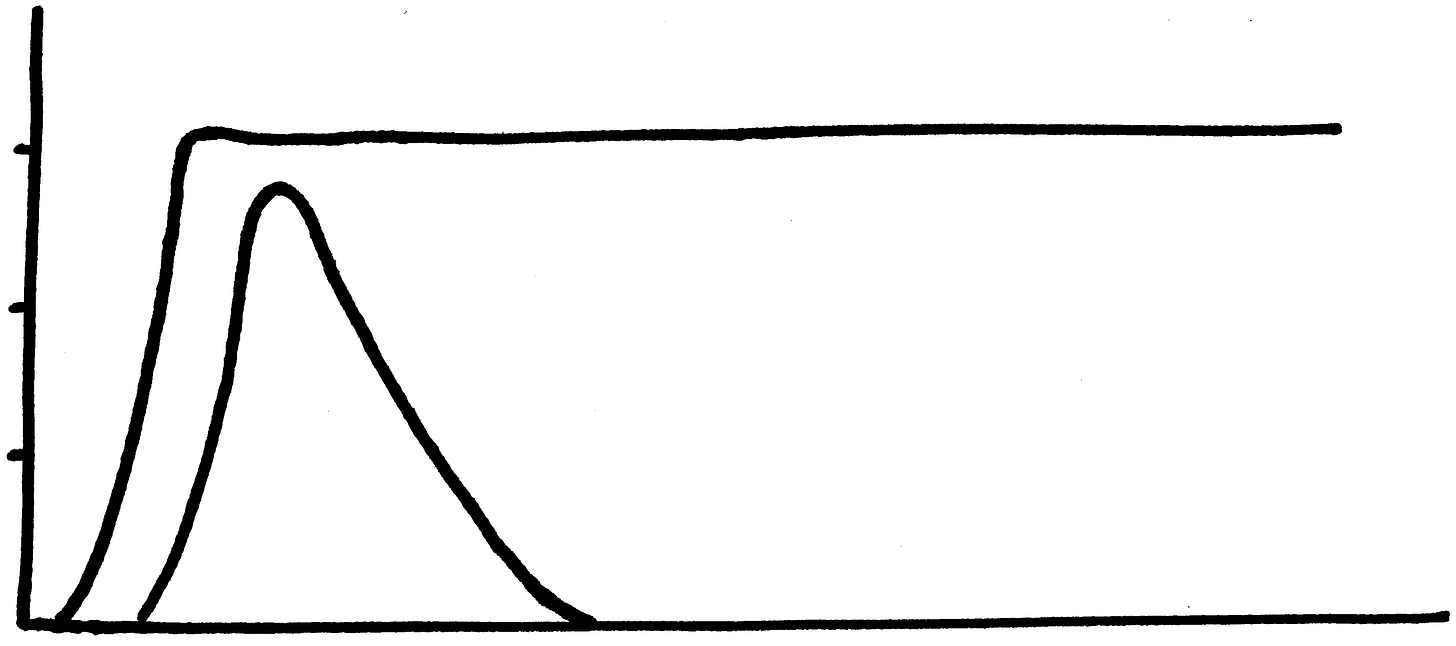

Which means that 2.9s tend to be forgotten much more easily, relative to 3s, than you would think, based on how similar in size they are. 3s get written down, whether literally or metaphorically; the guilty verdicts get recorded and the consequences stick in memory (and in many formal systems, after a couple of 3s in a row, further 3s start getting treated as if they were 4s or 5s or 6s; think three-strikes laws or traffic cops noticing that you’ve already been let off with a warning for a similar infraction).

2.9s, on the other hand, fade. Given sufficient time, they round to zero—at least, in the eyes of the system.

(Another piece of why they fade is that it’s generally seen as churlish or spiteful to keep track of them, where it’s generally not considered so with 3s. If I note aloud that someone else was (the equivalent of) tried and convicted and sentenced, I’m not docked points by default for doing the noting, because it’s treated as a sort of objective public fact. It’s fair game. If, on the other hand, I’m visibly paying attention to and tallying up transgressions that are below the threshold, this is often seen as weird or threatening or fundamentally unchill. There’s a (not entirely unreasonable) reaction of something like “hey, didn’t we all agree that stuff below this line was not a big deal? Isn’t that sort of why we have the line, in the first place?”)

The fading-away of low-level fuckups is good, for most people, most of the time. If you’re the sort of person who throws out a 2.9 every couple of years, when you’re unusually tired or clumsy or angry or inattentive, the rounding-to-zero means that you have room to make mistakes, that your embarrassing missteps won’t follow you around forever, that you don’t have to spend inordinate amounts of time atoning or apologizing, that if you are in fact deemed not guilty of a punishable offense then you will actually not be punished, etc.

But it also means that a thresholder can abuse and exploit the relatively shorter half-life of a 2.9 to get away with packing them in much more densely than someone can get away with, with 3s. If things were strictly proportional, you could do 2.9s only about 4% more often than you could do 3s, but between the existence of a threshold at 3 making 2.9 tantamount to “innocent,” the amnesia thing making it easier for people to lose track, and the churlishness thing making it costly for people to try to point out the pattern, it is in practice possible to do 2.9s way more frequently than 3s.

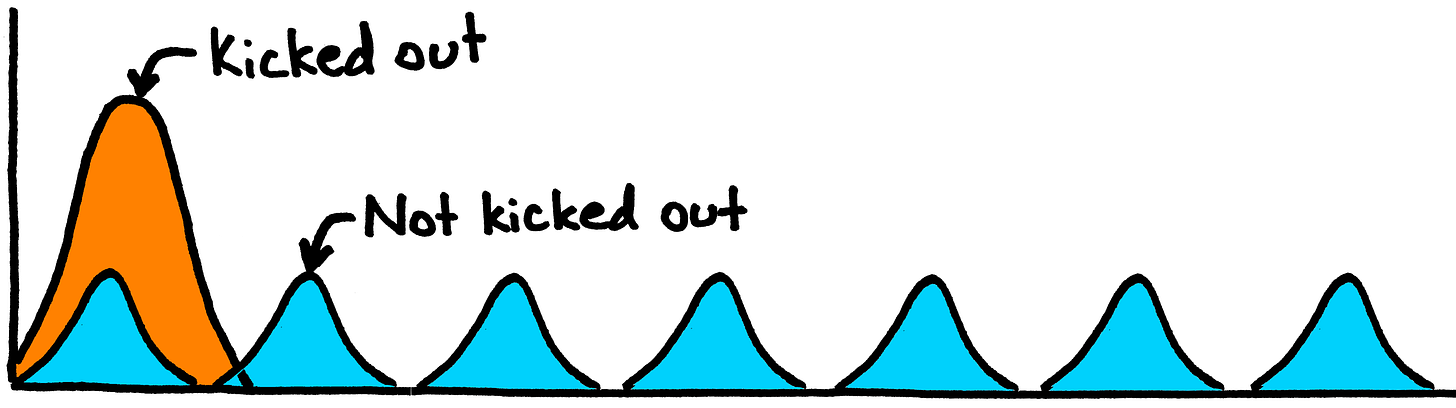

(Usually a thresholder will not literally do them back-to-back-to-back like this, because then the pattern becomes obvious, and the exploit depends at least in part on uncertainty and ambiguity, but the spirit of the above is what I’m gesturing at—as soon as it becomes actually tenable to actually get away with another 2.9, the thresholder goes for it. The more that each 2.9 happens to a different person, or in a different context, such that each onlooker only sees a fraction of the overall pattern, the easier it becomes. And in fact I’ve been in situations where the people who could see the whole pattern (e.g. the HR person receiving each separate complaint) was basically like “yes, I see what’s happening here, but there’s nothing I can do; rules are rules and my hands are tied, come back when they actually do a 3.”)

V.

As mentioned above, some rule systems do try to account for thresholding in a kinda-sorta way, such as highway patrol officers issuing formal, written warnings that will pop up if you get pulled over again (although the first infraction has to already be enough of a 3 to get you pulled over in the first place; they don’t really have a method for writing down stuff that’s bad-but-not-bad-enough-for-the-officer-to-intervene). Similarly, in soccer/football, two yellow cards in the same game gets you a red card; you can’t just stack up yellows ad infinitum.

But most formal rule systems seem (to me) to have no guardrails against thresholding whatsoever. Below the level of what qualifies for punishment, it’s a total free-for-all.

This is interesting (to me) because people, acting on their own moral and ethical intuitions, definitely do have guardrails against thresholding. When an individual is keeping track for themselves, they tend to notice thresholding quite quickly. Parents and teachers, for instance, will let certain borderline misbehaviors slide a few times, but then start cracking down. People will break up with romantic partners for stuff that was fine twice, but not four times in a row (or over and over again forever). Small, intimate workplaces (like startups) where individuals spend a lot of time together are pretty good at finding an official pretext for firing someone when that person’s actual problem was “you didn’t break any of our explicit rules or norms but you came right up to the line one too many times.”

But once people outsource things to The System, a sort of apathetic bystander effect seems (to me) to creep in, short-circuiting the usual fuzzy safeguards.

And it’s not clear to me why The System so rarely takes thresholding into account. I think it’s at least in part because The System is meant to be legible and clear, and its actions meant to be justifiable, and “you’re innocent until proven guilty unless you were innocent by too small a margin too many times” leaves an ugly taste in the mouth, and “we empowered this particular agent of the system to use their judgment” tends to backfire, resulting in the agent themselves being punished unless they have a rule book to hide behind.

But in Duncan-culture, thresholding is very much a part of The System. It’s recognized and accounted for, not just with yellow cards and three-strikes laws, but in every attempt to model natural human interaction.

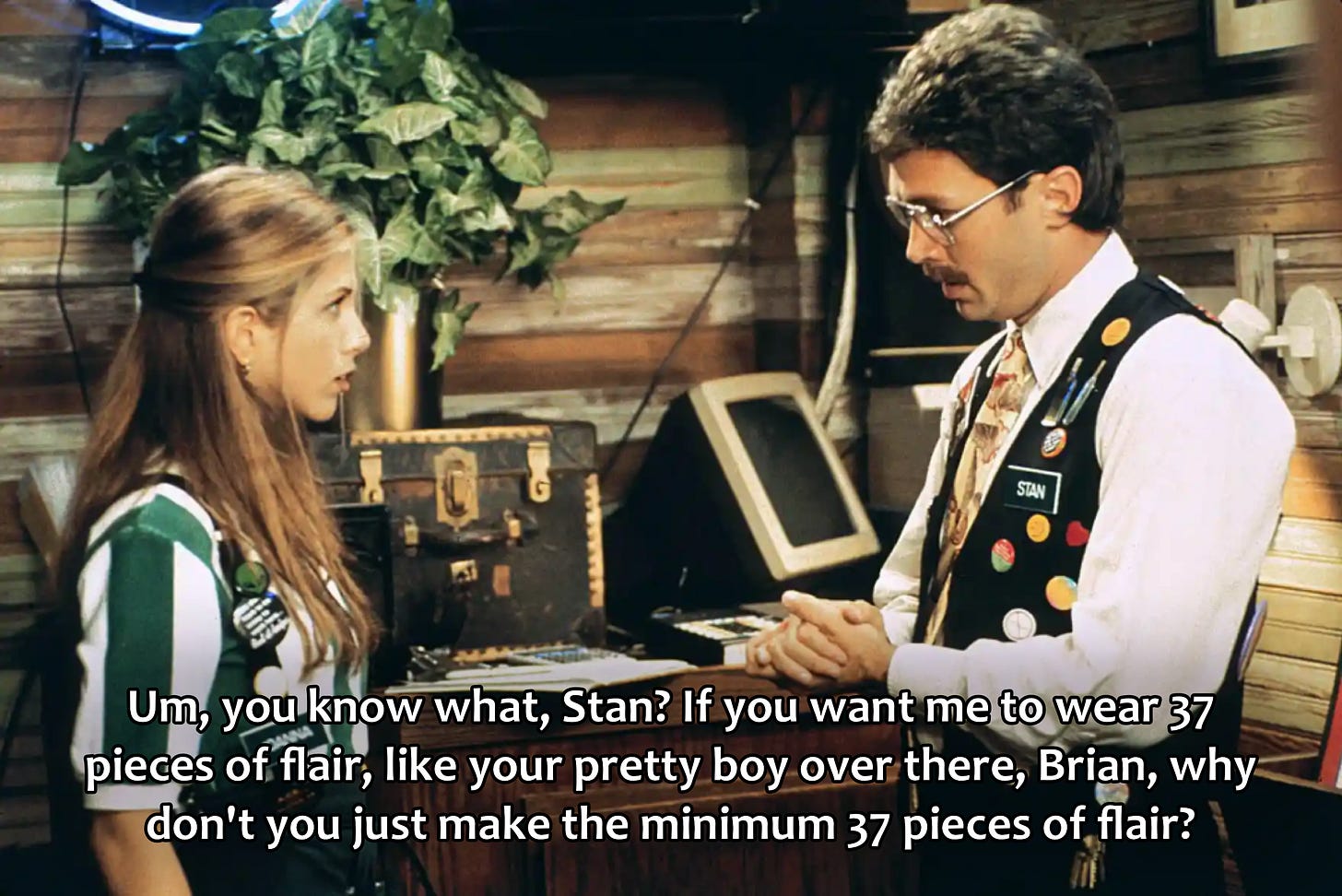

“Okay, but Duncan, I thought you were kinda autistically all about clear, explicit standards. It seems incongruous for you to say that the rule is ‘stay below 3’ but secretly the rule is ‘if you come within some unspecified distance of 3 some unspecified number of times, you’ll get in trouble’.”

I sympathize with this, but in fact this sort of is my complaint. Most rule systems (such as state laws, or employee handbooks) purport to lay out a clear and unambiguous standard, but in practice people do eventually start to accrue a sort of miasma of demerit-colored blegh even if they really were just trying to do what they were told, and can’t understand why following the directions they were given results in people glaring at them over and over again. Even if you win each individual battle, if you’re not doing thresholding on purpose, and are instead just a bewildered autistic, it’s not pleasant to find yourself called up in front of HR every time someone’s grumpy at you for following protocol to the letter, and it’s not pleasant to have people turn on you socially even if they can’t actually figure out a way to kick you out.

That’s why thresholding is explicitly addressed, in Duncan-culture rulebooks. The well-meaning oblivious people are told something like “yes, your actions in this case technically did not violate any rules, but the threshold is somewhat arbitrary and what you actually did was pretty close to punishable; now that you’ve had one near-miss you need to keep your conduct down under 2 for the next three months, because another 2.9 will be treated like a 4.”

(I’ve actually done this explicitly with people in this culture, in a variety of contexts, and to the best of my ability to judge even the non-autistic people generally found it reasonable, clarifying, and relieving.)

VI.

Things get harder, of course, when the systems get larger and more impersonal; it’s one thing for a teacher to tell that to a student and it’s different for a judge to enforce that when the defendant’s next case could very well come before a totally different judge with totally different standards.

I think that this is a crucial piece of understanding the puzzle of Trump, who is a world-class thresholder (although again he has other stuff going on, too, like preemptively training people to expect scurrilous behavior from him, and thereby getting away with it more easily than someone like John McCain would have—someone we expected better from).

In particular, understanding the way that thresholding builds up damage and resentment over time with no legal outlet for seeking recompense makes a lot of sense out of the left’s reaction to his 34 FELONIES (which were mostly actually just fractional pieces of the same overall fairly modest crime).

You see, both the people on the left and the people on the right have known that Trump was a thresholder all along—he sometimes brags about it explicitly, albeit without using that particular word. The people on the right find it hilarious and laudable, because they largely don’t think the system he’s flouting is good in the first place, and thus his sticking-it-to-the-man is part of his appeal.

And the people on the left have been fuming about it, because they can see the damage he’s doing to norms, to decency, to trust and cooperation, to critical institutions, to the very fabric of civil society, and they can’t stand (and in many cases, can’t understand) the fact that he keeps getting away with it.

So when Trump finally did slip up and do an unambiguous 3—

—only a 3, honestly, not like the 6s and 7s and 8s he gets away with by gaming the system or playing up uncertainty or whatever, most people on the left don’t want to admit it but the technically felonious behavior in his New York trial is way less bad, in an objective sense, than many of the other crimes that Trump has clearly committed, and not at all on the level of badness that people are trying to imply when they say “convicted felon”—

—when he finally slipped up and got himself unambiguously caught breaking the actual letter of the law, it was a lot like Leonardo DiCaprio winning an Oscar for his role in The Revenant. The left’s savage schadenfreude seems disproportionate because it is—it’s not really about minor bookkeeping fraud, it’s about the built-up pressure from Trump’s years and years and years of shittiness, both before and after his ascension to the presidency, none of which has managed to stick to him in a meaningful way until now.

(And even now, it seems more likely than not that this one won’t meaningfully stick, either.)

This is what happens with thresholding, when The System isn’t built to take it into account (and therefore doesn’t), and when the rest of the population can be divided-and-conquered, with those on Team Punish gesturing impotently at the vast pile of 2.9s and those on Team Lighten Up screaming “unfair!” and “vendetta!” This is why people cheer at characters like Batman and Rorschach and the Boondock Saints—because everybody knows that the system, for all that it lacks many of the flaws of mob justice, also lacks some of its virtues. If we were dealing with Trump the way that tribal humans would have dealt with him, back in Dunbar-number societies, he would’ve been thrown into a pit (or out into the wilds) decades ago.

But since we outsourced punishment to a formal system that doesn’t have any process in place for tracking and adding up 2.9s, we’re left with zero legal recourse for a (by this point) incredibly blatant and overt pattern of misbehavior that, in the aggregate, is easily as bad by this point as multiple 8s.

(I mean, the COVID deaths alone, especially in light of his clear foreknowledge as early as February and his refusal to take any responsibility at all…)

VII.

Okay, so: as an ambassador of Agor, what are my actual concrete recommendations?

First and foremost: start using the term “thresholding”—or point at the problem using your own words if you prefer, but do actually point at it.

This is one of those problems that largely goes away once everybody is clear about it being a problem—once people gain the ability to notice it happening, and have language for pointing at it and discussing it. Have your friends and family and colleagues read this essay, or summarize it for them. Ask them whether they agree that a string of 2.9s can ultimately be as bad or worse as a 6 or a 7 or an 8, and create common knowledge around the fact that thresholding is a thing that sometimes happens.

(It probably won’t be all that hard. A majority of people have had the experience of being burned by a thresholder in a context where The System refused to take action and all the authority figures said that Nothing Could Be Done.)

Second: once that common knowledge exists, and everybody in the relevant circles knows that everybody knows that this is a flaw in the system, reduce the stigma of keeping track. Make it virtuous to note down when someone has 2.9’d, so long as the noting is gentle and future-focused.

(Split and commit is an important background skill, here—you want people to be able to hold, in their own minds, something like “yeah, this was very probably just innocent obliviousness, and as such we’re going to let it slide, but just in case it was actually somebody testing the waters and getting ready to game the system, we’re going to keep an eye out and make sure we spot the pattern sooner rather than later.” You do in fact actually want to avoid punishing neurodivergents as if they were master criminals, but you also want to avoid letting master criminals use neurodivergence as a get-out-of-jail-free card.)

(Oh, and speaking of split and commit: notice that when someone first proposes “hey, I think we might be under a threshold attack, here,” it will probably feel like they’re crazy or hostile or overreacting! Thresholding is, by its very nature, a flying-under-the-radar sort of shittiness; a given listener may have had only one or even zero mildly bad experiences with the thresholder, especially if you catch it early. Almost by definition, it will seem like the person objecting is making too big of a deal out of things—if it didn’t, it wouldn’t be thresholding. But you also don’t want to create a culture where the very first accusation of an allegedly problematic pattern means someone gets tarred and feathered as a thresholder! Instead, you want people to be able to hold both hypotheses in their minds. To be able to keep in mind that maybe this person is abusing the threshold, and maybe they’re not, and remain open to the data over the following weeks and months.)

My third piece of advice is: follow through. Every veteran middle school teacher will tell you that if you threaten to respond to Behavior X with Consequence Y and then you don’t, you’re essentially training your students to dismiss and ignore you.

If you decide, in your council meetings, that the fourth 2.9 in a year counts as a 6, then you need to actually respond to the fourth 2.9 as if it were a 6. This includes being ready for, and pumping against, the inevitable “gosh, isn’t this overkill?” and “come on, those other things were so long ago and besides, they weren’t even all that bad!”

Interlude: There’s a skill here that’s important. It may seem like a system that carries out the harsher punishment for the fourth 2.9 is just scarier and meaner and less good to live under, but in point of fact, it’s the myopic focus on the smallness of each individual transgression, and the failure to perceive the larger pattern, that makes life really suck. If you make it clear that Behavior X consistently comes along with Cost Y, then it’s not actually the case that people will be unpleasantly surprised by Cost Y—instead, most of them will just avoid Behavior X. It’s inconsistency that creates resentment and feelings of unfairness—when the last three people didn’t have to pay Cost Y, but now all of a sudden you’re making me pay it.

When I was a middle school teacher, we had a school-wide rule that students were not supposed to use the bathroom during class. In my own sixth grade classroom, that meant that going would cost you five minutes sitting out at recess. Period—it didn’t matter if it was an emergency, didn’t matter if you were a model student or a delinquent—the price was the price.

In the other classrooms, if you asked to use the bathroom during class, the teacher would Weigh Your Soul, and Decide Whether You Meant It, and possibly levy a cost or not, depending on how they felt that morning and how convincing your distress was. Guess which class had both the least number of students using the bathroom and the least resentment and hurt feelings?)

The point is not that you have to build a system in which you increasingly punish 2.9s, by the way—that’s just one way to handle things, and in many contexts it’ll be too draconian. The point is that you want to alter your system to acknowledge the existence of thresholding at all. There are plenty of ways to do that. For instance, you could say that someone found innocent of a level-3 offense (because they only 2.9’d) needs to make sure to stay under 2 for the next couple of months—not increasing the penalty, but shifting the threshold. Or you could eschew penalties entirely, and have some other kind of response altogether, but have your response guide notice that one 2.9 is fundamentally different from three 2.9s in a quarter—that three 2.9s in a row is more than three times worse than a single 2.9 by itself.

And (of course!) whatever new system you put in place is still going to have thresholds, and it’s still going to be vulnerable to thresholding. That’s a relatively inescapable property of systems, period. The goal is not to forever solve the problem, it’s to make it harder for people to game the system (ideally in a way that doesn’t throw confused autistic people under the bus). “Well, there are always going to be ways for some bad actors to slip through the cracks” is a psy-op—it’s saying that, since perfection isn’t attainable, we shouldn’t try to make things better at all.

But obviously we should, and “improving the thresholding vulnerability” is easy, low-hanging fruit for many, many systems. If all you manage to do is make it twice as hard, and therefore only half as rewarding, you’ll have done a lot to make your local bubble nicer and more asshole-proof.

Good luck.

Man, this is why you are consistently in the same tier as Eliezer and Scott in my mind. Cleary naming an important phenomena while being compassionate and clear-headed about multiple perspectives on it in a way that makes me immediately want to tell all my friends.

At work, where we predict which ecommerce transactions are fraudulent and have financial incentive to be correct, we spent years being bitten by large fraud attacks where each individual transaction looked a bit suspicious but was not bad enough to block, and no assets tied all the transactions together in any obvious way. Eventually (finally) we began assessing the system as a whole and asking whether there was an elevated volume of just-under-the-threshold transactions in some segment of traffic. When there was, we lowered the threshold. For everyone. For a time.

And the reason we let fraudsters get away with it for so long is in large part because all of our systems were set up to assess One Single Transaction, plus other transactions concretely tied to it but explicitly not in any way that could set up a dangerous feedback loop, so none of our systems were set up to recognize the obvious-in-retrospect threshold attacks.

It's far simpler to narrow the scope of the problem to "assess this instance", and then your data model doesn't have a natural place to include global information and it doesn't fit through any of your nice interfaces. And you miss gigantic attacks on the system through myopia.

All that is to say (1) this for sure happens in ... "non-social"? contexts too, and (2) it can happen even if the thresholder isn't actually trying to be a thresholder. Though obviously a thresholder with *knowledge* of the rules can be a lot more efficient about it.