Truth or Dare

Or, Every Good Therapist Already Implicitly Understands Everything I Have To Say, Here, But Most Of Them Probably Haven't Put It Into Words So Maybe It's Still Useful

Structural note:

Some essays are like a five-minute morning news spot. Other essays are more like a 90-minute lecture.

This is one of the latter. It’s not necessarily complex or difficult; it could be a 90-minute lecture to seventh graders (especially ones with the right cultural background).

But this is, inescapably, a long-form piece, à la In Defense of Punch Bug or The MTG Color Wheel. It takes its time. It doesn’t apologize for its meandering (outside of this disclaimer). It asks you to sink deeply into a gestalt, to drift back and forth between seemingly unrelated concepts until you start to feel the way those concepts weave together, rather than just abstractly summarizing the interactions between them.

(There’s a big difference between the type of hike where you are trying to get from point A to point B, and the type of hike where the whole point is to embed yourself into the territory and be somewhere for a while. To let being-in-that-place do to you whatever it ends up doing.)

You certainly don’t have to set aside a single, uninterrupted afternoon to get value out of this piece—feel free to nibble away at it in chunks over the course of a week, treating each section like its own standalone essay. But the value is largely in the whole. Perhaps think of it as being like a movie, or an album, in the way that the experience of a movie or an album is fundamentally different from the experience of a Wikipedia synopsis. The thing I am trying to say here may well be compressible and summarizable, but I’m not trying to offer the summary. I’m trying to offer the thing itself. If I thought I could accomplish my aim with fewer words, I would have; I genuinely expect people who skip and skim to be underwhelmed in direct proportion to the shallowness of their engagement.

Sip and savor, as recommended, or do the other thing if that seems better. Make good choices, in accordance with your values.

0. Introduction

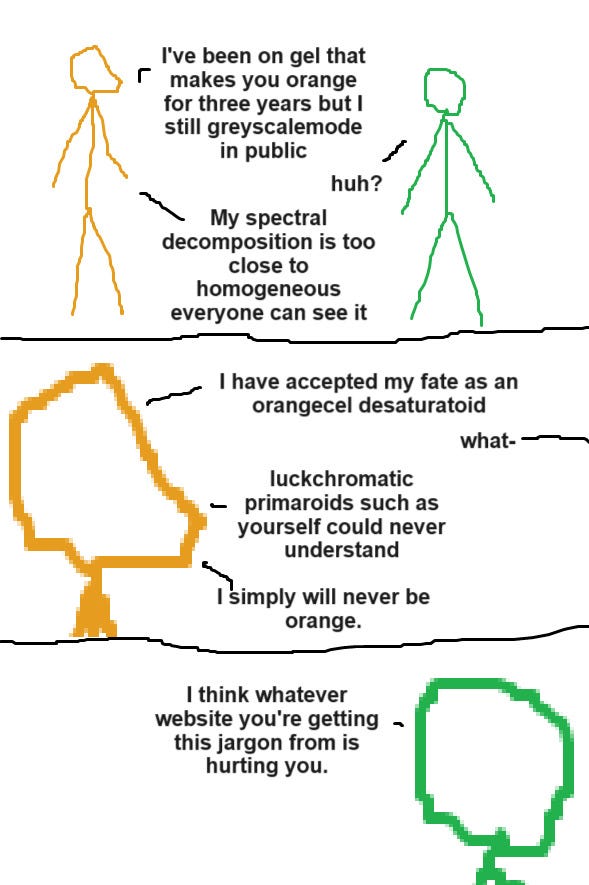

I received the above request while out and about a few weeks ago, and proceeded to spend most of my drive home narrating a response via voice-to-text. I ended up with an off-the-cuff list of about forty items, and I was pretty proud of it, so I posted it on Facebook and Discord for others to see.

(That list is copied at the end of this introduction, but I wanted to get to the thesis first.)

The responses were fascinatingly split. On the one hand:

It all just felt refreshing and raw and like being in that experience of truth or dare would contribute to my feelings of aliveness while increasing connection to other people (bonus points if I don’t really know the people? How exciting!)

and

hi yes when and where will u run this please i must be there

…and on the other hand:

Almost all of these strike me as demands for humiliation, and indeed as only worthy of being called “dares” at all on the premise that they are humiliating … the general surrender of autonomy involved in even granting others the right to impose these demands seems to me a lot like making oneself not-a-person.

and

After a quick scan of this list I can’t think of a single human being that I would be comfortable doing any of these with/in front of (including my beloved spouse of many years). Truth or Dare has always had, at minimum, a mildly threatening vibe in my experience.

S-tier physicist Richard Feynman once remarked that “all of the mystery of quantum mechanics” was contained within the double-slit experiment, and that a sufficiently careful thinker could extract the entire theory from that single observation.

S-tier Youtube philosopher CJtheX once took a 55-second excerpt from a Bo Burnham Netflix special and used it as an entry point to create one of the most important and relevant philosophical treatises I’ve encountered in the past two decades.

I’m not as clever as Feynman or CJ, but nevertheless I saw the above divergent responses to my silly little list of truths and dares and felt like I glimpsed the Matrix.

There’s an “everything” that I’ve been trying to capture in words (and feeling like I could capture, if I could only find the thread) for years, and in that moment it snapped into clarity, and that’s what this essay is about.

One gesture in the direction of the question I’m trying to answer is something like:

“It’s kind of wild, when you stop to think about it, that one person will experience this world as a cold and lonely and terrifyingly dangerous place full of abusers and manipulators and people who are not to be trusted, and another person who lives on the same street in the same city and went to the same schools with the same teachers and grew up with parents in the same economic bracket will experience it as warm and friendly and forgiving and safe, and both of these people will be able to present overwhelmingly compelling evidence in favor of these fundamentally incompatible worldviews. What, uh. What the fuck is going on?”

(c.f. the excellent Scott Alexander essay Different Worlds)

A bunch of people who knew me really quite well by that point, who were already strongly filtered and preselected for fitting in with my (pretty weird) Facebook bubble, all looked at the exact same artifact and had wildly different estimates of the threat that artifact posed. It was as if I had produced a horse, and half of the people were on team “don’t look a gift horse in the mouth,” and the other half were on team “beware Greeks geeks bearing gifts.”

(Honestly, the fact that English has one well-known idiom encouraging you to be suspicious of unexpected gifts, and another encouraging you to deliberately suppress your suspicion when offered a gift, is itself another pointer to this same phenomenon.)

To be clear: both of these different kinds of people believe what they believe for reasons, and their reasons seem … well, reasonable. When someone tells me that the world is unsafe, and I drill down into why they think that, I always find an actually unsafe world. I listen to their story and I feel like if I myself had lived through that same story I would indeed see things the same way they’re seeing things.

And when someone instead tells me that people are basically kind and good, and life is full of wonder, that also seems true. The world really does just seem to actually be like that, for them! Consistently so! It’s rare that I get the sense that either of these two people is miscalibrated in their reaction to the sum of their experiences.

Okay, but surely that’s just noise and variati—

Nope. One reason that this distinction feels worth writing about at all is that it doesn’t seem normally distributed, in my experience. Naively, I would have expected to see something like this:

…with the vast majority of people having a kind of middling view, and only a very small number reading to me as something like fundamentally optimistic or pessimistic—as being “shields-up” type Pokémon, versus “shields-down” type.

But when I do things like share a list of truths-and-dares, or publish a list of honestly pretty milquetoast rules of discourse, or propose starting a weird group house, or any number of other things that end up striking at this divide, what comes back looks more to me like this:

This seems to be the case even after trying to account for the fact that the people on the edges will tend to be more vocal. Something seems to be driving people out of the middle. I run into a lot more people who’ve had, like, eleven-out-of-twelve romantic relationships turn out super fucked-up and abusive (or, alternatively, completely lovely and drama-free) than I do half-and-halfers. And the same is true for money problems and employment experiences and even (depressingly) stuff like health and healthcare.

(One of the more unsettling truths about the world we live in is that something in the vicinity of half of all rape victims will be victimized a second time, whereas the odds of being victimized in the first place (at least in America) are more like one in five. Some estimates even claim the rate of a second assault is as high as two-out-of-three. Rape and molestation are not random horrors; they are somehow concentrated within a certain swath of the population.)

And I don’t like just leaving it at “this is a true fact about how the world works.” I think that [awareness that the other kind of person even exists, at all] is sorely lacking, and spreading that awareness is a noble and important goal in and of itself—

(which is why I’m constantly linking to Different Worlds in my writing, including probably multiple times in this very piece)

—but it’s not enough. I want to understand how the machine works. How did we get here? Why are people in the perceptual/conceptual/experiential buckets that they’re in? And how can we get them out?

My (attempts to provide) (partial) answers to these questions below.

Contents

Prologue (a list of truths and dares)

Act I

Scene I: How The Water Tastes To The Fishes

Scene II: The Chip on Mitchell’s Shoulder

Act II

Scene I: Bent Out Of Shape

Scene II: Going Stag, But Like … Together?

Scene III: Patterns, Projections, and Preconceptions

Interlude I

Act III

Scene I: Memetic Traps (Or, The Battle for the Soul of Morty Smith)

Scene II: The problem with Rhonda Byrne’s 2006 bestseller The Secret

Scene III: Escape velocity

Act IV

Scene I: Boy, putting Zack Davis’s name in a header will probably have Effects, huh

Scene II: Whence wholesomeness?

A list of truths and dares

• Sing a song you love out loud at the top of your lungs.

• What’s one thing you would be deeply ashamed to admit if Person X were here?

• What’s the best thing you’ve ever done that other people would think is awful?

• Spend the next minute upside down.

• Kiss the object in this room that you are most capable of expressing deep abiding love for.

• With the understanding that this topic is now off-limits for future truths, what is a topic that if people ask you about would be most likely to make you cry?

• If person X were willing to trade you a very valuable object in exchange for street cred, what sorts of things would you say about them to big them up?

• Get as physically close to person X as they will allow and whisper in their ear as softly as you can, ASMR style, nonstop, for a full minute.

• Using just your two hands, cover up/protect two spots on your body that you are not willing to have touched, and then close your eyes and let us all touch you for one minute.

• Look person X straight in the eye and tell us something that you have previously intentionally refrained from telling them.

• What's your most cherished memory that you think people won't understand?

• You have 90 seconds to make up a secret handshake with person X that uses as many body parts as possible.

• Draw a self portrait in 1 min.

• Draw the hottest person in the room in 1 min; we'll guess who it is.

• Think of a way that you could be touched by person X that you would genuinely expect to enjoy and feel a little bit vulnerable about, and then ask them to.

• Rank every person in the room.

• As quickly as possible, direct a sentence at each of us using the word fuck, but you have to use the word fuck differently in every sentence.

• Say “I love you” to each of us, but imbue it with a tone that makes it a true sentence in every case.

• Same thing, but “I hate you.”

• Same thing, but “I want you.”

• Same thing, but “go away.”

• Deputize one person to choose an item you must eat, and another to choose a person you must eat it off of, and a third to choose the body part you must eat it off of. (All three answers revealed simultaneously, no collusion.)

• Everybody else close your eyes. I dare you to touch on the shoulder the person in this room that you are fondest of, that you think knows it the least.

• Nominate the two people in this room that you think it would be most productive to see engage in a fight with heavy sexual undertones (a subsequent future dare is obvious, I hope).

• What’s something we could dare you to do that would set off an escalating cycle of revenge?

• Share something about yourself that you think genuinely has a chance of upsetting or repulsing someone in the room.

• Share something about yourself that you think genuinely has a chance of causing someone in the room to develop a bit of a crush on you.

• Spend the next two minutes doing whatever you can think of to genuinely cause yourself to fall more in love with person X.

• Break a bad habit of yours, right now, for real, forever (tell us what it is).

• Identify four body parts in this room that you find deeply attractive, and then separately identify their owners, but out of order so that we don’t know which is which.

• Who in this room do you find the scariest?

• Ask for something that you genuinely want.

• Defend yourself to a person of your choice in the circle.

• Who in this circle would you most want with you in a post-apocalyptic world?

• Who in this circle would you most want to fall with you through a gateway to Narnia?

• Why don’t you respect me?

• Ask for an appropriate punishment from someone in the room who has a reason to want to see you punished.

• Make a real apology right now. Doesn’t have to be to somebody in this room, but it has to happen right now; like, send a text if you gotta.

• What is the lowest price for which you would engage in a sexual act on someone in the circle?

• OK, I’m home now and I gotta do other stuff. Hope some of those were good.

Act I

Scene I: How The Water Tastes To The Fishes

I want to start off by reprising, in full, a mini-essay that I shared on Facebook and Discord roughly a year ago.

unfiltered meandering thought

there are so many little enclaves out there that just happen to have zero shitty people in them (either by luck or by filtering) and so much good stuff of so many incredibly varied kinds goes on in these enclaves, that is unlocked by the reliable absence of shittiness, which consistently shitty people never see and in many cases literally cannot even conceive of

like, i’ve been in multiple of these in my life (my teenage friend group, the international parkour community of ~2006, my teaching team at Voyager) and many times i have run into people who confidently assert that, like, such-and-such activity would never work, or such-and-such kind of trust is literally impossible, and i’m sitting there thinking of my consistent, repeated, direct personal experience to the contrary and i just … do not know how to bridge the gapand like, i can imagine ppl getting quite bristly at the cavalier use of a term like “shitty people” because indeed things do get very tricky and political and dangerous in the gray areas, there’s a lot of justified insecurity and anxiety around thresholds and it’s quite reasonable to view a term like that as a weapon because it is in fact straightforwardly wielded as a weapon a lot of the time

but also however big the gray area, and wherever you choose to draw the line, it’s nevertheless clear that if you just … look at the world, there’s a (fuzzy, ill-defined, multidimensional) thing there. like i feel pretty strongly defensive of my ability to say “sure, this is maybe more complicated than i’m gesturing at right now but also c’mon, be real, let’s call a spade a spade, let’s not fallacy-of-the-gray, here, we may not always be able to tell whether a specific X is darker than a specific Y if they’re pretty close, and things can be multidimensional/complex, it’s often gonna be pretty important whether something is red or blue or green or whatever, but also there is clearly such a thing as ‘very dark’ and it’s different from ‘very light’ in the obvious way”

and as a part of that, it just feels undeniable that, once you get far enough away from the indeterminate zone and out to where the water is just really unambiguously objectively clear, just deliciously pristine and empty of pollutants, so many possibilities open up and it’s simply amazing

and it’s amazing in ways that—

(uh, sorry, i dunno how to be tactful about this)

—it’s amazing in ways that, like, [the people whose presence and behavior by their very nature prevent those possibilities] often have a really hard time imagining, it sounds fake, it sounds like lies (in no small part b/c being unable to think outside of the box of your own direct experience (and your own projections/interpretations of it) is strongly comorbid with a bunch of different kinds of shittiness!)

A friend writes: Corroboration. I had many therapy clients who were gobsmacked to learn that, in some relationships, people are never intentionally mean/cruel/hostile to each other. These clients thought I was making it up. And I would very carefully define my terms, and be, like, “sure, sometimes people still disagree or want different things or even get upset or get hurt, but they never set out to hurt one another, they’re never vindictive, they don’t try to cause pain” and my clients were very ???? but how???

and it hopefully goes without saying that there are ways that people think I am shitty, and there are certain cultural branches that i don’t get to experience b/c those experiences can’t/don’t happen in my presence, because my presence would be destructive to them. i’m quite aware of these branches’ existence in an abstract sense and, from hearing about them and occasionally catching a glimpse of those enclaves, mostly i am just not at all envious of them/don’t want to experience them/don’t mind being excluded from them (honestly they mostly seem unpleasant and unfun to be in and the people who live there seem pretty unhappy).

but when i have these conversations with people who are some combination of envious and skeptical … when i try to describe just how amazingly good things can actually be, and very frequently are in my own direct experience, to people who have never experienced that level of awesome, because something about their way of being is corrosive to it, it’s like trying to explain a rainforest to a creature that lives in a barren, rocky desert on the edge of a steppe and whose excretions are toxic to all plant life (or something)

this is part of why i’m so keen on saving kids before they end up in that place, because i really do think most shittiness is learned, most shittiness is preventable, lots of shittiness is reversible, even, with the right support and training. some things are genetic and some injuries are Just Permanent but it seems to me that most kinds of shittiness are not an inherent or unalterable aspect of someone’s personality. most of the time it is actually possible to Stop Being Shitty but it’s harder the longer it’s been practiced/ingrained.

(but also the act of Saving People is like separate from the cool stuff that happens in the place where everyone’s already not shitty, you can’t do (most of) the cool stuff in the same place that you’re doing the rehabilitation, because the partial shittiness of a person in recovery is not appropriate for the place where the cool stuff is happening)

Ultimately, this is basically just Scott Alexander’s Different Worlds—the concept that people who are spatially adjacent can and often do have wildly non-adjacent experiences, but it’s a sad subset of Different Worlds in the sense that the particular axis of experience I’m gesturing at is, like, “awesomeness,” or “fractions-of-utopia,” or something. There’s a Different Worlds effect in the domain of “how great life can be, and how how high the ceiling is on how cool the stuff that goes on around you can be,” and it’s (unfortunately) (often) crucially dependent on something like your own ability to be non-shitty, which is often not entirely under a given person’s conscious control.

and it’d be nicer if this weren’t the case, and the cool chill people could just uplift the damaged/injured/confused/misguided shitty people no matter what, and bring everyone inside the enclave, but it simply Does Not Work, in practice. the very best gardens get that way, in part, by having the least amount of lead in the water supply, and lead golems, as a result, just … never get to enter them (except sometimes briefly, and destructively).

Okay, so, caveat: in a more serious essay (such as this one) I would indeed have been less cavalier about throwing around a word like “shitty.” I continue to maintain that there’s an important thing that that word is actually gesturing at fairly effectively, but (as later parts of the essay will address in detail) there’s not really a clear distinction between people who, uh, “smell like shit” because they are producing a bunch of shit, and people who smell like shit because shit has been smeared upon them.

(Or people who are producing a bunch of shit but it’s only because they’ve been fed a bunch of shit their whole lives and they’ve always lived in an environment where people just shit everywhere and so why would they do anything different, it would be weird and unfair to expect them to have invented good hygiene all on their own, concepts like “responsibility” get really tricky when the thing we’re talking about includes being responsible for what sort of world you find yourself a part of.)

In other words, I want to be more protective for the rest of this piece than I was in the above, of people who were put into the dark place that they currently live. Hurt people hurt people, and all that.

Going forward, I’ll be splitting “shittiness” apart into a few different properties:

The given concentration of metaphorical pollutants in an environment (how shitty the water is), and what that concentration implies about what sorts of creatures and behaviors can flourish there

The given concentration of pollutants in an individual (maybe something like how many “rads” they’ve absorbed? How much lead and mercury they’ve ingested?) and what impact that has on their character and experience

The emanation of pollutants from a given individual, out into the environment (i.e. the act of being shitty, and making the water around you worse, separate from the question of whether or not that’s on purpose or you’re ultimately culpable for it)

Speaking of that third one…

Scene II: The Chip on Mitchell’s Shoulder

One of my favorite obscure facts is that the phrase “chip on your shoulder” refers to a schoolyard tradition from the 1800s, in which one kid would place a woodchip on their shoulder as (essentially) a thrown gauntlet. If another kid knocked the chip off, the challenge was accepted and the fight was on.

(Interestingly, this meant that the chip-haver usually got the opportunity to throw the first punch, not the chip-knocker.)

“Walking around with a chip on your shoulder,” then, meant that, instead of issuing some specific challenge, you were the sort of person with an air of generic, unfocused belligerence, daring anyone and everyone to give you a pretext to lash out at them. Someone overtly provocative, trying to elicit the sort of pushback that would technically license aggression in response.

Not long ago, I had a brief-but-heated online altercation with a person I’ll lightly anonymize as Mitchell. It went roughly like this (I unfortunately don’t have access to the original thread):

Mitchell: [surprisingly strong negative claim about a friend of mine]

Duncan: [admittedly clumsy comment expressing surprise and confusion]

Mitchell: fuck off buddy

Duncan: ???

Duncan: Is there a reason you’re feeling particularly hair-trigger?

Mitchell: Do you honestly believe your comment wasn’t unambiguously rude?

Duncan: [explains why he thinks it wasn’t]

Narrator: This does not work.

There were a few more messages, none of which were particularly productive, and several of which involved Mitchell entrenching and escalating. I tried to take the conversation private, which also didn’t help (the following quotes are exact):

Duncan: Yo, seriously, wtf?

Duncan: like, any interest in checking whether maybe you misread me and brought some projections into this mix?

Mitchell: don't try this shit on me again

Mitchell: literally our last interaction years ago you tried this back channel manipulative bullshit

Mitchell: then you only unblock me so you can use me against cale

It’s pretty relevant that I had not unblocked Mitchell to “use” him against Cale[b] (who is a mentally ill serial harasser who’d been trying to infiltrate our mutual social circles and is currently in jail).

What had actually happened is that I’d had Mitchell blocked, but had been shown screenshots of him being direct and clear with Caleb in a way I found admirable, and had subsequently unblocked him without fanfare. After several months of uneventful non-interaction, I sent Mitchell a single, brief heads-up that Caleb was posting about attending one of his events, despite having been explicitly disinvited. Mitchell’s “fuck off buddy” were his first words to me since “thanks” after that heads up.

I lost my temper in the private conversation and ended up reblocking about three sentences later. Out of morbid curiosity, I scrolled back to refresh my memory on what had caused me to block Mitchell the first time, years earlier. Lo and behold, the previous altercation had also been a case in which Mitchell had been bizarrely and confusingly hostile.

Duncan: I'm curious if you're already getting messages being like “wow, what’s Duncan's problem in that thread?” because I'm getting messages saying “wow, what's Mitchell’s?”

In other words: there was a clear and persistent pattern of Mitchell receiving ambiguous evidence and interpreting it (extremely) negatively with (great) confidence, justified in no small part by how he’d previously interpreted ambiguous evidence negatively. He was sure I was being a jerk in the conversation about my friend because he knew I’d been a jerk in the Caleb interaction because he knew I’d been a jerk back in 2020, etc. etc. etc.

To be clear, the claim here isn’t that people aren’t persistently, stealthily shitty. They often are! That’s not a ridiculous hypothesis to hold.

But the thing about hypotheses is, you have to (or at least ought to) actually investigate them. What was missing in Mitchell’s interactions with me was a sort of split-and-commit, many-conflicts-are-the-result-of-miscommunications-and-mistakes kind of humility. There’s a certain type of check that Mitchell was not doing, and had zero interest in doing, where he would take some sort of action that would allow him to distinguish between worlds where Duncan was in fact trying to get away with being a dick, and worlds where Duncan was just being clumsy or following a slightly different set of conversational norms.

(Mitchell also wasn’t running these checks re: my friend, which left me much more suspicious of the negative summaries he presented of that friend’s behavior than I would be if those same summaries had been given by someone with passable epistemic hygiene.)

And the reason he wasn’t running those checks is that (from his perspective) he didn’t need to. Obviously I was being a dick (and so was my friend)! Obviously our intentions in all of these interactions were overtly hostile. You don’t run checks to confirm that the sky is blue. Of course the sky is blue. It’s such a self-evident fact that it’s the canonical example of a-thing-that-everybody-knows.

Act II

Scene I: Bent Out Of Shape

There’s a relatively common aphorism that I’ve usually heard expressed as:

“If you run into an asshole in the morning, you ran into an asshole. If you run into assholes all day long, you’re the asshole.”

A prion is a kind of malformed protein. Wikipedia says they look like this:

Prions cause disease (most famously mad cow disease, which causes dementia and death and has no cure). They do so via a sort of molecular zombie apocalypse—prions are shaped such that they cause other proteins to similarly become malformed. If you put a prion next to a healthy protein (of the right kind), pretty soon you have two prions.

I won’t belabor the metaphor, but it’s worth noting that, in the interaction with Mitchell, I started off entirely well-intentioned, and ended angry and hostile. I’m far from the calmest, longest-fused individual, but I am actually pretty friendly by default, and I even tried two or three times to reset and get back on the right foot before eventually ending up in you know what? Fuck that guy territory.

(Which is where Mitchell began.)

The “behave like an asshole → other people respond with assholery” pathway is a fairly well-known one, but it’s not the only way that malformed social behaviors can act like a prion disease.

Another snippet of a past post:

Sometimes, people who live in a sadder, scarier, more dangerous world than you do try to drag you down into their smaller, more frightening experience—usually while being entirely well-meaning, offering advice that is friendly and entirely appropriate for their darker context, not realizing that things can really actually for-real be Different and Better than what they know to be true.

"I'm just trying to protect you!" they say, while inadvertently making everything worse (because some things really are self-fulfilling prophecies; reality distortion bubbles exist and you really can call the darkness down upon yourself to a certain degree and in certain contexts).

Scott Alexander, elaborating on a nearby point:

I remember when I was younger, I used to want to meet my friends from the Internet, and my parents were horrified, and had all of these objections like “What if they’re pedophiles who befriended you so they could molest you?” or “What if they’re kidnappers who befriended you so they could kidnap you?” or less lurid possibilities like “What if they’re creepy drug people and they insist on bringing you along to their creepy drug abuse sessions and won’t let you say no?”

And I never developed a good plan that countered their concerns, like “I will bring pepper spray so I can defend myself.” It was more about rolling my eyes and telling them that never happened in real life, it was more in the realm of terrorism (the kind of stuff you hear about on the news) than the realm of car accidents (the stuff that happens to real people and that you must be guarding yourself against at every moment). I’ve now met hundreds of Internet friends, and I was absolutely right—it’s never happened, and any effort I put into developing a plan would have been effort wasted.

This is also how I think of people turning out to be abusers. It’s possible that anyone I date could turn out to be an abuser, just like it’s possible I could be killed by a terrorist, but it’s not something likely enough that I’m going to take strong precautions against it. This is obviously a function of my personal situations, but it’s a real function of my personal situation, which like my Internet-friend-meeting has consistently been confirmed over a bunch of different situations.

One interesting thing about Tumblr and the SJsphere in particular is that because its members come disproportionately from marginalized communities, it has this sort of natural prior of “people often turn out to be abusers, every situation has to be made abuser-proof or else it will be a catastrophe.” I once dated someone I knew on Tumblr who did a weird test on me where (sorry, won’t give more details) they deliberately put me in a situation where I could have abused them to see what I would do. When they told me about this months later, I was pretty offended—did I really seem so potentially abusive that I had to be specifically cleared by some procedure? And people explained to me that there’s this whole other culture where somebody being an abuser is, if not the norm, at least high enough to worry about with everyone.

I’m not sure what percent of the population is more like me vs. more like my date. But I think there’s a failure mode where someone from a high-trust culture starts what they think is a perfectly reasonable institution, and someone from a low-trust culture says “that’s awful, you didn’t make any effort to guard against abusers!” And then the person from the high-trust culture gets angry, because they’re being accused of being a potential abuser, which to them sounds as silly as being accused of being a potential terrorist (if you told your Muslim friend you wouldn’t hang out with him without some safeguards in case he turned out to be a terrorist, my guess is he’d get pretty upset). And then the person from the low-trust culture gets angry, because the person has just dismissed out of hand (or even gotten angry about) a commonsense attempt to avoid abuse, and who but an abuser would do something like that?

The good things that happen in the high-trust culture—the good things you can get from being expansive and unworried, if your environment supports/allows it—those good things break and disappear if enough people start to make low-trust moves. The low-trust attractor starts to bend other people into reciprocal low-trust shapes, just like a prion twisting nearby proteins. There's a reason people say things like “ugh ... he got inside my head.” The getting-inside-the-head can have actual impacts on systems that would have been fine otherwise.

As one example: gift economies and cultures-of-reciprocity are high-trust. They’re built upon and implicitly foster a kind of abundance mindset (paradoxically via a form of eternal indebtedness in which everyone feels like they owe everyone else generosity, in response to past generosity received). You helped me move my couch, so I’ll help you mend your fence; neither one of us can remember who got dinner last time but I think it’s my turn (and if it’s not, who cares; in the long run we all come out ahead, together).

A habit of tracing debts and costs precisely, on the other hand, is low-trust. I only ate $23 of food, so I only want to pay $23 of the bill; I can drive you to the airport, but only if you reimburse me for gas and also I have to leave work an hour early, which means I’m losing an hour off my paycheck, hint hint…

Suddenly, there’s an implication that I don’t expect to be made whole in the natural course of affairs—that you need to be managed and parented and policed into making it up to me. Suddenly, debt isn’t a bond between us, but something to be erased as quickly as possible (which brings with it the implication that interactions need to pay off on a short time horizon, further implying a pessimistic view of our long-term relationship). Gifts cease to be symbols of generic fellow-feeling and become fungible commodities, with market logic corroding and replacing social ties.

And once one member of the group enters this mode, it’s rare for the others to succeed at staying loose and expansive; as long as Jordan is insisting on paying back and being paid back, I might as well pay back Morgan, too…

(There’s an extensive body of research on how gift economies and cultures of reciprocity die when exposed to this sort of low-trust commodification; see the works of e.g. Marcel Mauss, Karl Polanyi, David Graeber, Lewis Hyde, James Carrier, and Nancy Munn, among others.)

(It’s not that markets aren’t great—they are! Capitalism has done more to drive innovation and raise vast swaths of the population out of poverty than any other system. But capitalism that reaches all the way down into your intimate relationships can twist and poison those relationships very quickly.)

(It’s not that money isn’t great—it is! I love giving and receiving money, including among friends and close partners. But there’s a huge difference between including money in your gift economy, as just one more way to be generous, and replacing your gift economy with an interpersonal market.)

Another social disease with a prion-like mechanism is paternalism. Overprotection, helicopter parenting, the sort of cover-your-ass mentality that chooses guaranteed soul atrophy over small risks of potentially devastating injury.

That’s a picture of my child, Cadence. The climb they’re tackling involves hauling themselves up a bunch of ropes that are spaced about eighteen inches apart, including a brief traverse at the top (to the platform just barely visible on the left) where there’s a risk of falling about six feet straight down onto metal.

Cadence is almost two, and is pretty big for their age, so they’re no longer super conspicuously the youngest kid being allowed to attempt this climb. A few months ago, though, the dirty looks and whispered comments were constant.

“Isn’t that dangerous?”

“Aren’t you terrified?”

“Oh my god—whose baby is this?”

I’m pretty weird, and I’m pretty contrarian, so I mostly just smiled and shrugged it off, but even I could feel the immense pressure to cave, to conform, to restrict Cadence to the “normal” amount of risk (i.e. the amount of risk that the least confident parent present felt comfortable with). It wasn’t that any parents were trying to explicitly peer pressure me. They were just … being prions. Their anxiety rolled off of them in waves, conjuring vivid images of broken bones and visits from child protective services.

You see the same thing with all sorts of anxieties. There’s a kind of “oh, gosh, I never thought of that, but now that you mention it…” that precedes a sort of awful soul contraction, and it’s only made worse when you add in the layer of social judgment/fear of being held to account after the fact if you don’t take preventive action and something ends up going wrong.

There’s a story that I’m quite fond of retelling, about a moment of prion resistance. It took place when I was about nineteen years old, and an instructor at a local martial arts academy.

…Kelly was my protégé, the second of what ended up being four, by the time I left. He was maybe thirteen or so at the time. In addition to teaching him Tae Kwon Do, I would sometimes pick him up from school in the afternoons and take him around the city to do parkour until his parents got off work. It would just be the two of us, alone for hours, often in weird places like back alleys and loading docks and rooftops.

One day, an acrobatics troupe came to a city about two and a half hours away. They were amazing, and after I saw them myself, I immediately called Kelly’s parents to ask if I could take him with me to a repeat of the show the following weekend. They said they’d think about it, and called me back half an hour later to say yes.

When Kelly got in the car on the morning of the trip, he was blushing and embarrassed. “Aaaaaaawkward conversation with my parents this morning,” he said, as we drove off.

“Oh?”

“Yeah. They were like, ‘so, you’ve never really been this far away from home on your own, outside of like school trips or whatever.’”

“Uh huh.”

“And then they were like, ‘and you’ve never spent a full day all by yourself with Duncan.’”

“Mmm.”

“And then they said ‘okay, well, keep your phone on, and if he tries anything funny, use some of that Tae Kwon Do he’s been teaching you.’”

And that was it. We laughed for a bit about how awkward it was, and then we drifted to other topics, and just generally had an awesome road trip.

But the way Kelly’s parents handled that situation has stuck with me ever since. They didn’t play dumb. They didn’t plug their ears. They acknowledged—directly to their son’s face!—look, this is a rough world, there’s a nonzero chance that this older male will try to mess with you in a way that is Not Okay.

But at the same time, they didn’t let that become the ultimate deciding factor. They didn’t choose to absolutely minimize risk, at the cost of what ended up being a terrific afternoon. I can’t actually get inside their heads, but I have to guess that, as parents, they made the decision that a life constrained by fear is ultimately worse than a life lived out loud, and free. They trusted their son’s judgment, and they trusted me, and they rolled the dice with their eyes open.

This story is like my list of truths and dares. When I tell it, I get two very, very different reactions, from people who live in two very different worlds.

Scene II: Going Stag, But Like … Together?

Okay, okay, but in the spirit of fairness and not being a jerk:

For the most part, people don’t set out to reduce trust and break the bonds of reciprocity and raise their kids with crippling anxiety. Most of the people who are meticulously tracking debt and risk would rather not, but simply don’t feel that they have the luxury to be lax about it.

(Again: every time I’ve double-clicked on someone like Mitchell, I’ve found what seem like basically sensible reasons for why they are the way they are.)

A “stag hunt” is a thought experiment in psychology and behavioral economics, like the trolley problem or the prisoners’ dilemma. It’s a game of resources and cooperation. There are usually multiple rounds, and in each round you pick one of two options, e.g.:

Rabbit (spend 2 of your existing resources, get back 3)

Stag (spend 5, get back 10 if everyone else chooses stag)

The idea is that anyone can go out and snare a rabbit by themselves with 2 units of effort, without coordinating with anyone else, but rabbits aren’t very big and don’t offer much in the way of food and fur and other things of value. Stags are much more attractive game, but they’re difficult to catch, and it takes everyone working together smoothly all day to bring one down.

At first blush, “everybody choosing stag” seems like a slam dunk, much like cooperating in the prisoners’ dilemma. If you had a machine where you could reliably put in $5 and get back $10, you’d probably do that a lot.

But in practice, things get tricky very quickly. Imagine, for instance, that the five people playing the game have the following resources “in the bank”:

Alexis: 15

Blake: 12

Cameron: 9

Dallas: 7

Elliott: 5

…obviously they should all choose stag, right? The resulting balances will be 20, 17, 14, 12, and 10.

But imagine the situation where a stag hunt is attempted, but unsuccessful. Let’s say that Blake quietly decides to hunt rabbit while everyone else chooses stag.

(Why would Blake do that? Any number of reasons. Maybe Blake has beef with someone. Maybe Blake didn’t get the memo, or lost track of which day it was. Maybe Blake doesn’t believe there is a stag out there, as in the version of the game where even perfect coordination comes with a 10% chance of failure. Maybe Alexis was pushing super hard for a stag hunt and Blake had valid hesitations but couldn’t get a word in edgewise and feels sort of shut down and shouted out and socially threatened. Maybe Blake has secret insider knowledge that someone else is planning on choosing rabbit, and Alexis just wouldn’t listen.)

What happens? Blake spends two and gets three. Everybody else spends five and gets back zero, because the stag slipped through the gap where Blake was supposed to be.

Alexis: 10 (or 10.6 if they all bully Blake into divvying up the lone rabbit)

Blake: 13 (or 10.6)

Cameron: 4 (or 4.6)

Dallas: 2 (or 2.6)

Elliott: 0 (or 0.6)

(Ah, another possible motivation for Blake: becoming relatively richer; tying or surpassing Alexis in the game of keeping-up-with-the-neighbors.)

If you’re Elliott, this is a super scary scenario to imagine. If you commit to a stag hunt and it doesn’t work out, you will be completely broke—you won’t even have the necessary resources to hunt rabbit, after such a devastating loss.

And so, if you’re Elliott, it’s tempting to preemptively choose rabbit yourself. If there’s even a slim chance that the other players might defect, or that the hunt might fail for other reasons, then you have a strong motivation to self-protectively husband your resources. Choosing rabbit means you go from 5 to 6 (or, in the world where you’re the only one with a rabbit and you’re forced to share, that you fall from 5 to 3.6 instead of all the way to zero).

Now imagine that you’re Dallas, thinking through all of this. You can handle one stag hunt going poorly; you’d still have enough resources to go out and hunt rabbit and slowly build yourself back up again. But you’re only one disaster away from a long, unpleasant slog out of poverty, and meanwhile Blake and Elliott are both looking pretty shifty from where you’re sitting and Alexis doesn’t seem to be taking their hesitation seriously at all…

It’s not that you’re fundamentally opposed to hunting stag—you’re just opposed to wild optimism and the wanton, frivolous burning of resources. If there’s a discussion, you’re going to be pretty tempted to argue that everyone hunt rabbit for another week or two, building up a buffer before going out and taking such a big risk.

Meanwhile, if you’re Alexis, you’re likely starting to feel pretty frustrated. I mean, can’t these people see that we’d all be better off if we just pitch in, together? How is this even a hard call? Why are Dallas and Elliott preemptively talking about rabbits when we haven’t even tried catching a stag, yet?

According to me, the value of thinking about stag hunts isn’t to find a solution—

(Although there are little bits of practical wisdom to be gained from the thought experiment, such as “ah, you should maybe like actually ensure buy-in, which as a prerequisite means creating sufficient social safety that people will honestly report their fears and hesitations rather than being shamed into silence or nodding while secretly disagreeing or whatever.”)

—so much as it is to understand (and empathize with) why people do the thing. There’s a tendency for the privileged and the well-resourced to (wrongly) dismiss rabbit-choosers as stupid, selfish, short-sighted, lacking ambition, uncooperative, defectors.

But there has to actually be an agreement, in order for someone to defect on it. Assumed consensus is not consensus.

(I still eat at Chick-fil-A, despite many people’s attempts to paint this as crossing a picket line that never, in fact, actually formed.)

(Thinking about stag hunts also makes it easier to see what sorts of things foster successful collaboration. For instance, if Alexis really, truly wants a stag hunt, and really, truly believes that it will be disproportionately beneficial for everyone, then it would go a long way if they’d e.g. offer to cover Dallas and Elliott’s losses, in the event that things go wrong, or even just give them some spare resources up front. Something something, if we’re going to pretend we’re a community, let’s act like one.)

Scene III: Patterns, Projections, and Preconceptions

Sometimes, police officers murder innocent, unarmed people.

Sometimes, these murders take place under circumstances in which the officer claims to have thought that the victim was raising a weapon. Usually, it turns out that the “weapon” in question was a wallet, or a phone, or nothing.

Setting aside:

a) whether being threatened with a weapon should justify reflexive lethal response, or whether police in particular should be trained and held to a higher standard than the normal rules of self-defense, and

b) whether some fraction of those officers are making up the “I saw a gun” excuse entirely,

it seems clear to me that at least some times, these reports are straightforwardly honest. The officers (at least some of whom are genuinely horrified and remorseful) really actually perceived a non-existent gun in the hands of the victim, often with surprising detail and verisimilitude. The threat, from their perspective, was 100% real.

This is important. The fact that this sort of thing can happen is important.

When people who have been blind since birth receive drugs or operations that allow them to see, they don’t just suddenly “have vision.” Heartwarming tiktoks of babies putting on glasses for the first time notwithstanding, it takes time for the brain to figure out what to do with all the incoming data. Stuff like motion and contrast detection can come online within days or weeks, but it can take months or even years to get a grip on object recognition and spatial relationships. Many people never make it to what we would call “normal” vision, even if all of the machinery is in place and functioning perfectly.

Take a look around you right now. Imagine for a moment that you don’t have access to cached concepts like “tree” and “phone” and “desk” and even “hands.” Try to back out toward raw perception, the whorls of color and contrast that your brain is actually receiving and “effortlessly” translating into a coherent visual map.

It’s a lot.

It’s a lot.

When you were a baby, you didn’t have that map. You put it together, piece by piece, as your eyes and brain matured in tandem, in part by just … not actually trying to process most of it.

A huge part of how the system works is expectation. Your brain is not actually analyzing and interpreting all of the information that’s streaming in—not even close.

(Not even close even given that the actual high-resolution sharp-focus part of your vision is really, really small. We see less than we think we do, and even so we’re working with a much smaller fraction of the actual data than it feels like we are.)

The vast majority of what comes in goes straight in the garbage. Instead, your brain has a sense of what sorts of things it ought to be seeing, and it lazily kinda-looks to make sure that nothing important has changed since the last system cycle, while filling in the gaps according to your preconceptions. If you’re really actually paying attention, it does a slightly better job of staying up-to-date with actual reality, but even then your top-down expectations can, and often do, overwhelm your bottom-up perceptions.

(Which is how police officers in high-stress situations can hallucinate guns that aren’t there—can really actually see them, even though there aren’t any gun-photons entering their retinas.)

I’m about to say a bunch of things fairly quickly.

One thing that I’m going to say in fewer-words-than-it-probably-deserves is that visual input is not a special category. It’s not just light-entering-the-retinas that gets ruthlessly filtered and mostly ignored. Our brains are shutting out almost everything, all the time. They have to, because reality is overwhelmingly loud and complex. We can’t navigate it without first chunking and simplifying and categorizing, brushing past all of the noise and chaos and dreaming ourselves into a world of (a small, manageable number of) static, sensible, comprehensible objects following mostly-predictable scripts.

(Put another way: we only comprehend that which is within the bounds of our comprehension; everything we’re not capable of absorbing we, uh, end up not taking into account.)

Another thing I’m going to say very quickly is that human brains are, in general, confirmation bias machines. We do not, by default, look for things that will surprise us, and disprove our hypotheses, and overturn our assumptions. We tend to be receptive mostly to supporting evidence for the stuff we already expect and believe, and we almost always manage to find things that can be interpreted as such.

These two facts by themselves are already nearly sufficient to explain the difference between the two types of Pokémon. If your implicit standard of evidence is “can I find twenty or thirty examples of X being true,” this is achievable for almost any X. Start out expecting that people are basically good, and you’ll find plenty of proof. Start out with the opposite belief, and you’ll find plenty of proof. If a given slice of reality contains ten thousand comprehensible things, and your brain can hold maybe a dozen at a time, it’s not at all hard to fill up those dozen slots with a biased selection that matches your preexisting world view.

(Another thing that I will say too quickly is that our brains have reinforcement loops around salience. If, for whatever reason, I start to pay particular attention to the color

my brain will pretty quickly “get the message” and start feeding me yellow percepts more readily, which will make yellow things a larger part of my minute-to-minute experience, which my brain will respond to by getting better at perceiving yellow, and before long, if nothing interrupts the process, the whole thing turns into a cup-stacking skill.)

(I have no idea if this clever trick will actually work, but the hope was that with just three seconds of priming, I would get your brain to notice that there’s really actually quite a lot of yellow in the above image, even though at a glance the most prominent color is probably red.)

(Anyway, did you notice how much blue there is?)

(Also, did you notice how instantaneously and effortlessly your brain was, like, “I know what this is; I am looking at a crowd of people”? Probably without ever actually zooming in on any specific individual, to confirm? The same thing is likely to happen with the image below, even though closer inspection reveals … well …)

The overall claim that I’m making here is something like the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, in linguistics—that your preexisting concepts shape and filter your experience to a substantial degree. Except it’s not just a side effect of language, it’s a side effect of all of your preconceptions, verbal and nonverbal alike. I don’t know how many “things” a given person can “have their radar on” for (maybe it’s a dozen and maybe it’s a few hundred) but it’s certainly not all of the things, all of the time, such that your perception of the ratio of A to B to C to D to E is likely to be balanced and reflective of the actual ratio of A to B to C to D to E, out there in reality.

The world is sufficiently full of stuff that, if you have your radar on for (let’s say) sexism, you’re going to find sexism—a lot of it, all the time.

And if you have your radar on for (let’s say) acts of grace and kindness, you’re going to find acts of grace and kindness. A lot of them, all the time.

There's a thing that I've been doing without quite being consciously aware of it, and I became consciously aware of it over the past few days, and then a DunCon attendee complimented me on it explicitly (which was super nice). The thing is, basically: “Roll dice that have a 9/10 chance of a really good payout and a 1/10 chance of significant but absorbable disaster.”

I think I did this with adding Caleb Ditchfield to my Discord server as a mod (an instance of 1/10 disaster). I think I did this with the invitees to my afterparty once DunCon was over. I think I did this with DunCon itself. I think I did this with the most recent visitor to Grass Valley, who is someone I couldn't honestly say I knew when I said “yes” to a visit (I'm usually pretty protective of this space, but it felt like a 9/10 die).

And I think that I'm doing this more often than a lot of people around me are doing it? Not highly confident about that. But I recommend it in part because there's a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy involved. If, thanks to background safety/resources/privilege, you're able to sort of aggressively self-signal “it's fine and it's going to be fine,” this creates an open expansiveness that (most of the time) tastes really really good and enables really really good things (and once in a while blows up).

It's maybe easier to see if you flip it around: if someone is aggressively signaling a sort of creeping, cringing carefulness, and is visibly anxious and worried, and clearly fretting and doing loads and loads of contingency planning...

...this makes people slow down? Makes people think/feel “ah, there must be danger here, I should raise my shields and proceed with caution.” Which is also self-fulfilling.

It’s like the colors red and yellow and blue in the Where’s Waldo image above. People like to tease Jordan Peterson for noting that “there are cathedrals everywhere for those with the eyes to see,” but he’s right—it’s just that he neglected to mention that there are also dumpster fires everywhere, for those with the eyes to see dumpster fires. There’s X everywhere for those with the eyes to see, for almost any arbitrary value of X. It’s trained Youtube content algorithms all the way down, an endless feed of more like that.

And—crucially—you are not in control of which things you have your radar on for. Not totally. Certainly not in the sense that you can quickly and easily turn on (or turn off) your brain’s tendency to perceive the things it’s practiced at seeing. Your mind has grooves worn into it by years and years of repetition, and it’s generally not easy to escape those grooves, and the process of carving new ones is often slow.

(Again: I’m saying a lot of stuff very quickly. Please do useful things with your awareness of that fact.)

When you wake up in the morning, there’s a set of things that your brain is expecting to encounter, and is (on some level) looking for. Stuff that it’s good at looking for, and good at finding. Stuff that you will, in fact, find, because if you lived in a context where that stuff was not findable, your brain wouldn’t have feedback-looped into its current state of being really good at finding it, and would instead be really good at finding something else. Stuff that past experience has taught your brain to anticipate.

And the stuff that your brain is reflexively distilling out of the noise and chaos is going to be different from the stuff the next guy’s brain is distilling. Or at least, there’s no guarantee that your brain and the next guy’s brain are going to be equally skilled at extracting the same things out of reality. There’s enough going on, and enough variation in people’s experiences and upbringing and temperaments and predispositions, that even people whose lives seem very similar from the outside can nevertheless end up specialized in very different directions.

(Still going fast.) This is why split-and-commit is a prerequisite for the responsible adoption and use of labels like “sealioning” or “gaslighting” or “projecting” or “abuse.” Explanatory categories are seductive and powerful—it’s dangerous to give someone a sticky, sense-making concept, if they don’t have the meta-skills necessary to keep that concept in check, make sure it doesn’t overtake and overpower their actual observations.

(My spouse Logan spent the better part of the past five years working on a framework for helping people see the world more clearly, in part so that those people could better solve their sticky and intractable problems, and by far the thing Logan found they needed most was training in abandoning their preexisting conceptual buckets. In learning how to actually unclench their fingers and let go, to step outside of the ontology, the perspective, the worldview that was keeping them stuck inside their maladaptive patterns.)

(Okay, apparently I’m also going to end the section and shift gears very quickly, too. Exit, pursued by the concept of a bear.)

Interlude: The Sound of One Hand Clapping

For reasons of wanting you to do something like “actually swim in this stuff; actually mull and linger and let it sink in,” I have up to this point intentionally avoided giving a crisp, tight summary of what I think is going on. But here’s the basic mechanism that I’ve been obliquely describing (some of this is a summary/retread and some of this is looking ahead to the remaining sections):

A person has an experience or two.

Those experiences cause the person to crystallize something. To notice a pattern or a phenomenon; to pick up on a particular cause-effect relationship; to get a sense of this-is-how-the-world-works.

That noticing acts as a filter, causing them to be more attentive and more receptive to future observations that fit the pattern. If you’re sensitized to see mushrooms, suddenly you see a lot more mushrooms.

People change shape in response. People who find themselves surrounded by things-to-fear become fearful, and anxious, and tend to contract. People who find themselves surrounded by safety and abundance and opportunity become optimistic, and ambitious, and tend to expand. (et cetera, for all sorts of traits on all sorts of axes; this is not a single binary.)

The environment shifts, in response to that changed shape.

Partially this takes place via prion-like mechanisms and reality distortion fields, where people unconsciously elicit behavior that matches the vibe they are holding and emanating (e.g. people with a chip on their shoulder finding that indeed they are surrounded by angry people all the time, people who have capybara vibes finding that people are universally nice and reasonable).

Partially this takes place via selection effects, where e.g. someone sends one too many “I am anxious and high-maintenance” signals, and the cool chill low-maintenance people who don’t want their cool chill low-maintenance vibe damaged just … stop inviting them.

A feedback loop emerges. The person’s experience becomes more like what they were initially sensitized to see and expect, which leads them to act in ways that are appropriate to those expectations, which elicits appropriate responses from the environment in turn.

Clusters of homogenized world begin to take shape. e.g. all the cool chill low-maintenance people end up in one distributed network, with few connections to the distributed network containing all the anxious, high-maintenance people.

Steep slopes develop. The high-trust world ejects people who don’t meet its standards. People living in the low-trust world try out trust, as an experiment, because it seems to work out so well for their cousin whose life is so happy and fulfilled, but the context in which they try out their trust experiments contains large numbers of people who have no practice in trust, and large numbers of predators who were kicked out of the high-trust circles but know how to fake trustworthiness sufficiently well to fool someone who’s only ever had glimpses of the real thing. Damage occurs. Worldviews become entrenched. The mental filters become even stronger. The corpus of evidence backing up the worldview thickens; escape becomes even less likely and people advocating for the existence of A Better Way sound progressively more insane and out of touch (and/or progressively more like con artists).

Duncan posts about Truth or Dare and people interpret it according to their preconceptions, in a way that doesn’t feel like interpreting something according to a preconception, it just feels like recognizing it for the straightforward attempt at humiliation that it so obviously and inarguably is.

Act III

Scene I: Memetic Traps (Or, The Battle for the Soul of Morty Smith)

One of the things that is most salient to me about Christianity—

(and, in my experience, most underappreciated by people critical of Christians)

—is just how hard it is to think your way out of it, from the inside. If you start from a truly Christian perspective, wherein The Lord Works In Mysterious Ways, and Unthinking Faith Is A Virtue Actually, and Let’s Not Forget The Story Of Job, and The Influence Of Satan Is Everywhere And Is Specifically Designed To Seduce You Away From The Truth So You Shouldn’t Necessarily Trust The Evidence Of Your Eyes Or Your Reasoning Or The Words Of Non-Believers—

(Plus the whole thing about Your Immortal Soul Is Genuinely At Stake, Maybe You Should Just Take Pascal’s Wager.)

If you start from a place of taking Christianity seriously, it’s actually very, very difficult to work your way, step by step, to the conclusion that Christianity is false. The set of premises you’re working with have been subjected to heavy evolutionary pressures to cause them to fit together tightly and smoothly, with no gaps that would make it easy to pry one of them loose. The tools that you’ve been handed are designed to slip. For two thousand years, every time someone came up with the sort of argument that would have caused many Christians to abandon their faith, Christianity responded.

Sometimes, it responded via clever Christians in monasteries and seminaries coming up with new counterarguments and convincing-sounding pseudologic.

Sometimes it responded by ceding ground, abandoning some tenuous or unpopular claim—Christians today are somewhat less likely than they used to be to insist that prayer will reliably heal any wound or sickness, or that the faithful will always triumph in battle, or that God wants black and indigenous folk to submit to the superior wisdom of the white man, et cetera.

Sometimes it responded in ways that routed around the inconvenient argument entirely, such as through violence, or by mocking and refusing to engage with it/making it seem low-status to even consider (“pshhh, so you think humans came from monkeys, huh?”).

And sometimes it responded by evaporative cooling, i.e. the argument did in fact cause many Christians to abandon their faith, and the remaining faithful were thereby selected for some combination of stubbornness or credulousness or disregard-for-epistemics or increased social cohesion or whatever, and the uphill battle became even steeper for anyone else still stuck inside.

It’s a memetic trap, in which any bit of evidence that might reasonably give one pause has a preexisting, ready-made argument for why it doesn’t actually mean what it seems to mean. If you’re really, properly wedged inside the Christian perspective, there simply aren’t any clear and easy paths out.

The same is true for people in Mitchell’s position.

When you live in The Dark World, it’s just really really hard to escape. If you have a strong prior on (e.g.) self-serving Machiavellian manipulation as the motivating instinct behind someone else’s behavior, there isn’t much that person can do to convince you that they’re not doing stuff for self-serving, Machiavellian, manipulative reasons.

(Setting out to convince you is already sort of self-defeating, at that point.)

(After all, if you would by default conclude that they weren’t self-serving and Machiavellian if they just did X, then boy oh boy isn’t X exactly what a sufficiently clever sociopath would do, to lull you into a false sense of security—)

Cynicism and antipathy are (or at least can become) fully generalizable arguments, proof against any observations that might point in the other direction, just as evidence of the Christian god’s nonexistence can be reinterpreted as a deliberate test of faith, or the manipulations of Satan, etc. If you’re a sufficiently determined misanthropist, there’s always a corrupt, profane explanation.

(Or if you’re just sufficiently suspicious/anxious/underconfident/fearful; “they’re being nice to me out of pity” is almost as corrosive as “they’re trying to con me.”)

(This is basically the explanation for why my culture also views child molestation with a great deal of horror, despite lacking a Puritan tradition that treats sex as fundamentally dangerous or dirty or corrupting—because what a child molester is doing is setting a young and impressionable brain on a self-sustaining negative trajectory. If you teach a kid that hey, actually, the world is made up of betrayal and pain and shame and isolation and loss-of-control and no-one-coming-to-save-you, that kid will believe you, and that kid’s brain will go on expecting those things, and accruing more and more evidence that the world is indeed dark, and it doesn’t take very long at all for that sort of snowball to become too big to stop or redirect.)

The show Rick and Morty centers on the relationship between the titular Rick Sanchez—a multiverse-hopping sociopathic genius inventor with a drinking problem—and his grandson Morty, a basically ordinary fourteen-year-old boy who he drags with him on insane adventures with dubious consent. It covers a lot of ground, and hits on a surprisingly wide range of themes, but one of the major reasons that I fell in love with it is that, for a brief and glorious moment, it was the only show on television that was making high art out of the messy reality of parenting.

(Morty’s actual parents, Beth and Jerry, are main characters too; Beth is Rick’s daughter and has plenty of father issues; there are multiple episodes in which some version of Morty ends up a father himself. But by far the most meaningful parental relationship in the show is the one between Morty and Rick.)

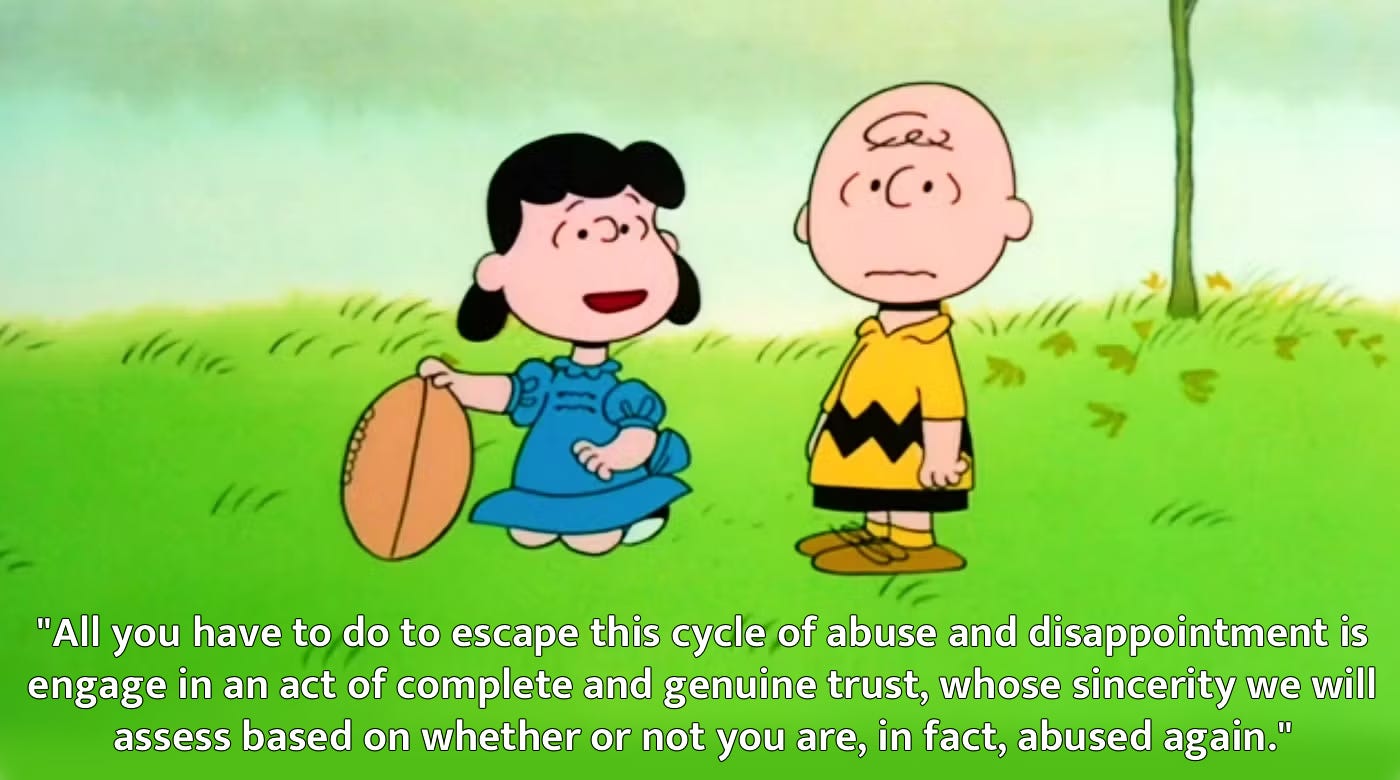

I’m jumping around a little bit, but there’s a deeply unsettling comic that is also about parenting, in precisely the same way, that seems like a good place to start:

You see, Rick is in control of Morty. Not in the sense that he is, at any given moment, exercising control. Morty spends most of his minutes on the show acting more-or-less autonomously.

But Rick is unambiguously in the driver’s seat. He retains ultimate power. He has—more than once!—dragged Morty away, not just from his friends and family, but from his entire reality, uprooting him and depositing him unceremoniously into an alternative version of his own life (usually via a method that involves making Morty literally bury the corpse of a doppelganger).

He controls whether or not Morty goes to school. He arbitrarily chooses which memories Morty is allowed to retain. He makes multiple clandestine alterations to Morty’s mind and body and DNA, virtually never with Morty’s knowledge or permission. On top of that, he also pushes Morty around in all of the normal ways—bullying, mockery, manipulation (and, begrudgingly, also flattery and admiration and genuine affection; abusers never are pure evil, or they’d be much easier to escape).

(The youth rights activist in me points out that, actually, it’s all normal, in the sense that Rick doesn’t do anything that’s fundamentally outside of the realm of what most American parents consider entirely within their prerogative. Controlling Morty’s movements, deciding which relationships he’s allowed to maintain, trespassing on his privacy and bodily autonomy, forcing him into various activities regardless of interest, subjecting him to endless propaganda and relentless emotional and psychological pressure—the science fiction setting of the show cranks it to eleven, but it’s like using robots or zombies to make a allegorical point about present-day society. In the end, Rick’s treatment of his grandson is only extreme in its magnitude, not in its core nature. I think hope that Rick and Morty is trying to draw attention to this, on purpose, though I may be giving the showrunners too much credit—it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between a savage satirical skewer and a story written by a person who just thinks that’s what normal is.)

What makes the-parts-of-the-show-that-are-about-parenting compelling to me is that Rick clearly cannot decide what to do with the knife. To the extent that Rick and Morty is about the ongoing battle for Morty Smith’s soul, that battle is primarily being fought inside Rick. It’s Dark Rick versus (the surviving, resentful fragments of) Light Rick, and the ultimate outcome is genuinely anybody’s guess.

(Again I see this as a mere heightening of ordinary reality, rather than a departure into full-blown fantasy—most parents do not seem to me to behave coherently toward their children, in the sense of having an actual philosophy that they allow to actually constrain their actions. Rather, the biggest determinant of whether a child is about to have a good day or a bad one mostly seems to be whether the parent happens to show up as Dr. Jekyll or as Mr. Hyde.)

Rick is a nihilist. He’s also a narcissist, a hedonist, and a solipsist. He’s also suicidally depressed.

(These traits are not unrelated.)

He spends half of his time floundering in ennui, preemptively sneering at concepts like “meaning” and “purpose” and “connection” in a transparent and only-partially-successful attempt to stop himself from feeling the acute pain of their absence.

(He spends the other half idly toying with forces beyond comprehension and sometimes nurturing petty grievances into unimaginably elaborate revenge schemes.)

Morty, on the other hand, is—well, a kid. Which is to say: he is an as-yet-unruined whole and (relatively) healthy person. He has morals (if shaky ones). He has fears (where Rick has only apathy). He has loves (and lusts). He has an intact capacity for awe and wonder and curiosity, and pushes back against his grandfather’s bleak derision with the intermittent fervor of someone who’s pretty sure they’re in the right, but expects to lose the argument anyway.

“You sold a gun to a guy that kills people! Selling a gun to a hitman is the same as pulling the trigger.”

“It’s also the same as doing nothing. If Krombopulous Michael wants someone dead, there’s not a lot anyone can do to stop him. That’s why he does it for a living.”

And Rick clearly finds all of these traits infuriating, threatening, tedious, and admirable, in turn. He vacillates wildly between explicitly trying to burn them out of his grandson (and thereby forging him into Rick 2.0) and going to extreme, even self-sacrificial lengths to preserve and nurture them.

(And thereby … forging him into Rick 2.0? In a very different, yet equally valid sense.)

It’s pretty easy to see through the flimsy narrativemancy that Rick is deploying in order to justify some of his crueler manipulations—it’s the same sort of stuff that abusive parents have said since the beginning of the species. It’s a cold world out there, you’ve got to be tough to survive, you gotta learn or they’ll eat you alive, blah blah blah.

It’s also easy to see that it’s not all self-deception and rationalization. It is a cold world out there. Morty does need to be tough(er than he is) to survive. There are untold horrors in the universe of Rick and Morty, and they are in fact often trying to eat Morty alive. Throughout the course of the show, we see countless alternate-reality versions of him die in all sorts of horrifying ways, often downstream of the very traits that Rick finds so viscerally offensive.

(But A can be a valid justification for B while not being the actual reason someone is doing B. The fact that some of Rick’s abuse is incidentally useful for helping Morty grow doesn’t mean Rick is doing it in service of that growth.)

(Except that sometimes he is? The show is beautifully unwilling to oversimplify.)

And yet.

As Rick plummets into a timeless abyss, having used (essentially) the last parachute on his grandson, he murmurs to himself “be good, Morty. Be better than me.”

As Morty emerges from a bathroom, quivering and traumatized from a sudden and shocking near-miss with a rapist—

(who he had to physically fight off with a level of violence that would itself be traumatizing all on its own)

—Rick, unaware of specifics but immediately picking up on the shift in Morty’s state, suddenly switches from contempt to comfort, insisting that they finish the adventure he’s been deriding all day long, asserting that hey, the universe is a crazy and chaotic place, that’s why it’s a good thing people like you are around to clean it up every now and then.

As Morty comes back to his senses after being driven into a murderous rage, Rick lies to him, reassuring him that he was drugged, that he isn’t culpable, that the-person-he-was-being over the previous hour isn’t the real him, the real him wouldn’t do that, is better than that, wasn’t really at fault.

(Which he wasn’t, in the sense that Morty tried to avoid the inciting situation altogether, was forced into it by Rick, and only acquiesced and went along in a misguided attempt to save an innocent from an angry mob, after which things went sideways multiple times in a row until finally all of his repressed trauma was dragged to the surface.)

Being as charitable as possible to Rick, the central dilemma facing him is which parts of Morty he has to amputate and cauterize, in order to give the remainder the best possible shot at survival and happiness. Rick knows that his grandson’s softness—his kindness—his humanity—make him vulnerable.

But he also knows that those are the parts that make life worth living. He knows this intimately, because it was in losing those very same parts of himself that his own life ceased to be of value (even to him).

He’s trying to decide, in other words, just how dark of a dark world to shove Morty into. Just how dark to make Morty, under the assumption that Morty needs to be as-dark-or-darker than the environment he finds himself in, if he is to survive.

Hey Duncan, what's the significance of your cherry blossom hoodie? You mentioned it in terms that made it sound like there was Content there.

"soft"

but like, spiritually and psychologically

it represents a sort of being-allowed-to-be and embracing-of soft that is ... difficult, and a little bit alien, for a twelve-year-old boy raised in middle class 90's America, but which is in fact actually healthy and good

like “no soft allowed” being part of the toxic part of masculinity

I've only tentatively and stutteringly started practicing relaxing into softness at all in just the past few years b/c I spent the vast majority of my early life extremely armored up, because being extremely armored up was extremely necessary (world not shaped for Duncans, world is suddener than we fancy it, world is crazier and more of it than we think)

it only recently became sufficiently safe + something I even bothered trying to do + something I seriously considered rather than preemptively scoffing at

And the hoodie is a symbol of this in that, like.

“That doesn't look like something boy!Duncan would wear.”

“Why not, though?”

“..............huh.”

e.g. parts of this post from a couple years ago:

I have yet to find an explanation for hardness being superior to softness that doesn't ground out in some specific risk or danger or threat or need. Often people have a difficult time really taking seriously the hypothetical “okay, but what if that risk were really truly gone?” and they end up answering as if the risk were still obviously present, as if it fundamentally can’t be got rid of—